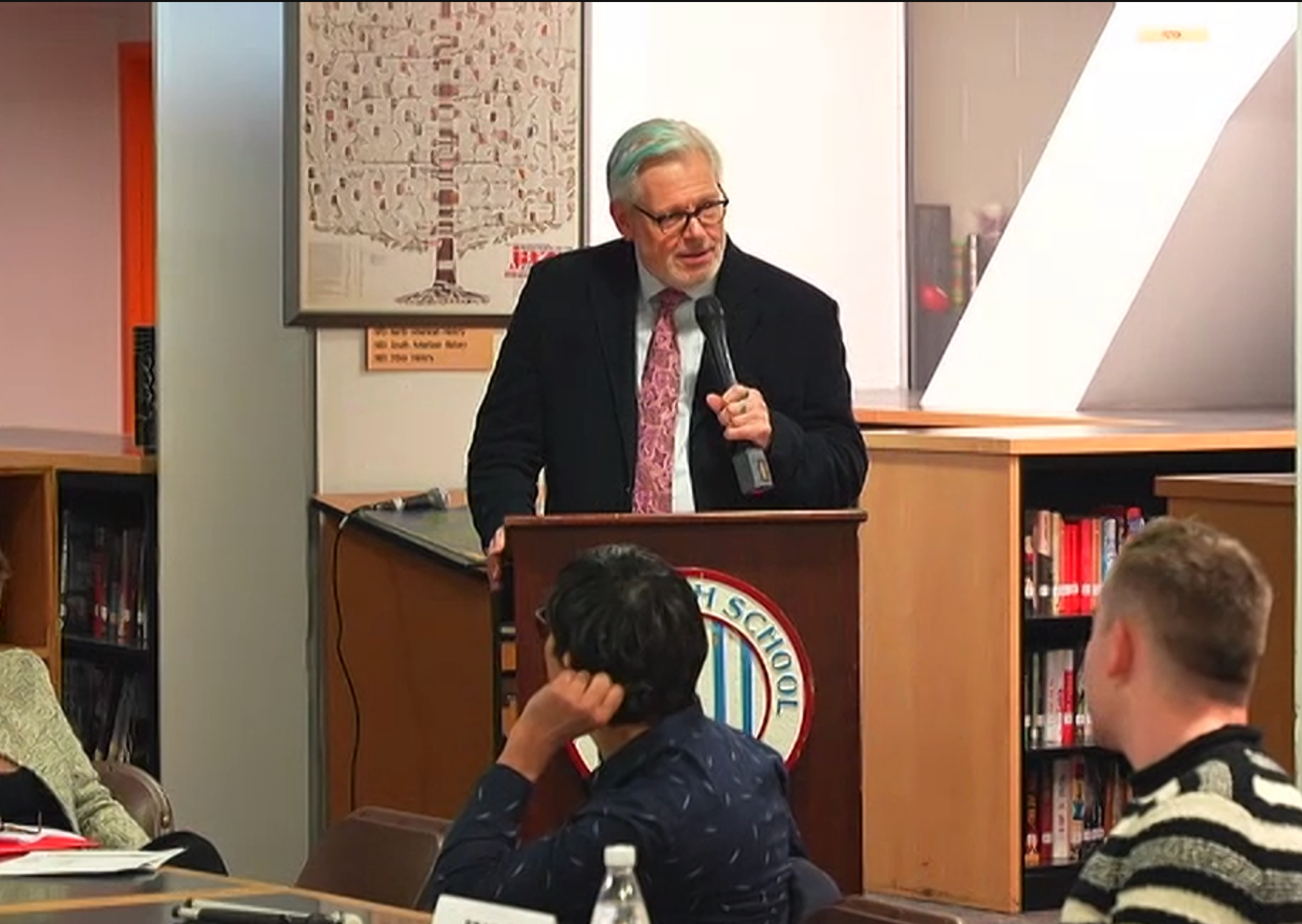

The NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project represents 25 years of work by founders Andrew Dolkart, Ken Lustbader, and Jay Shockley to document significant sites in the history of of LGBT people in New York City. Visit the project website to explore.

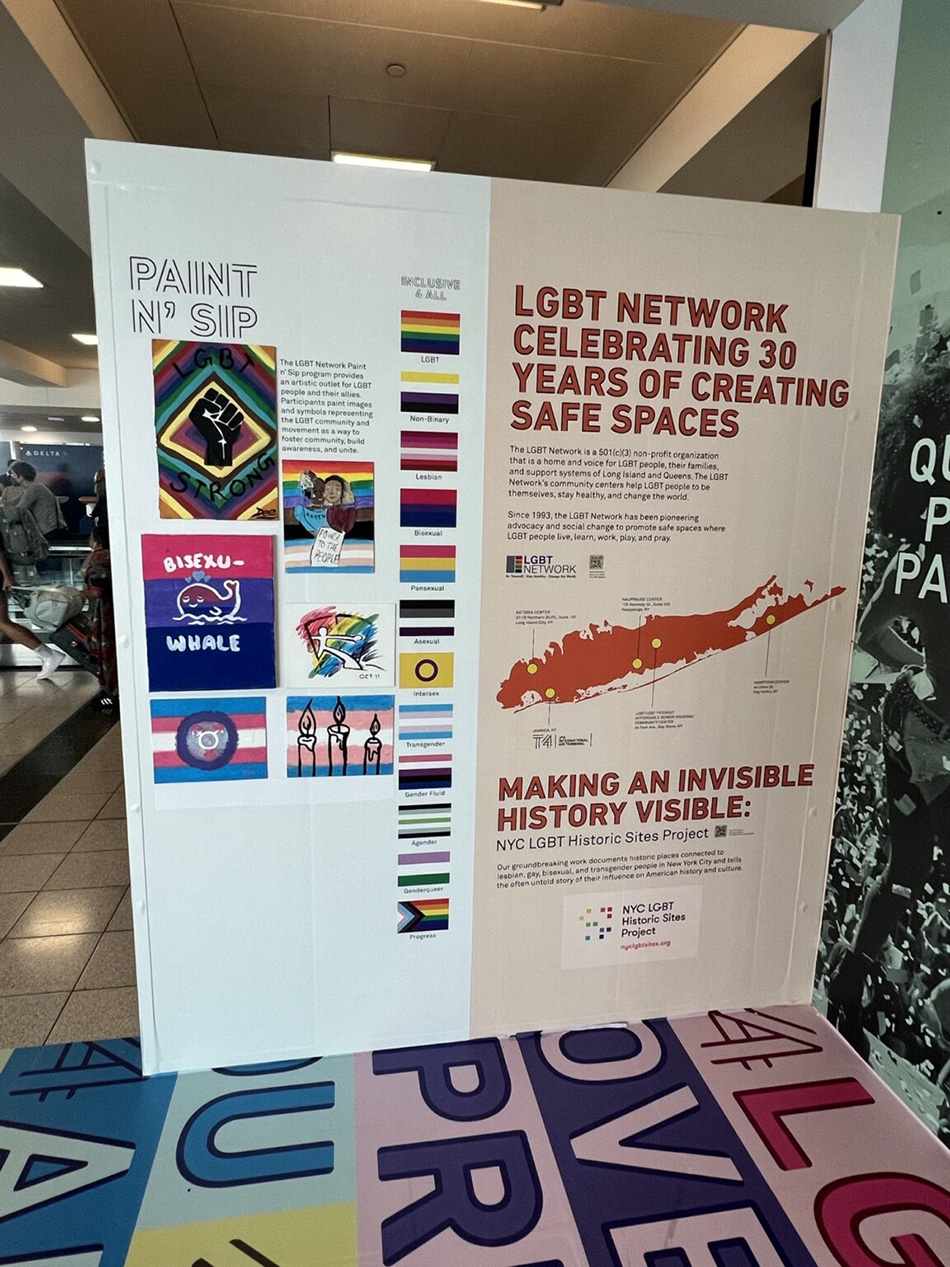

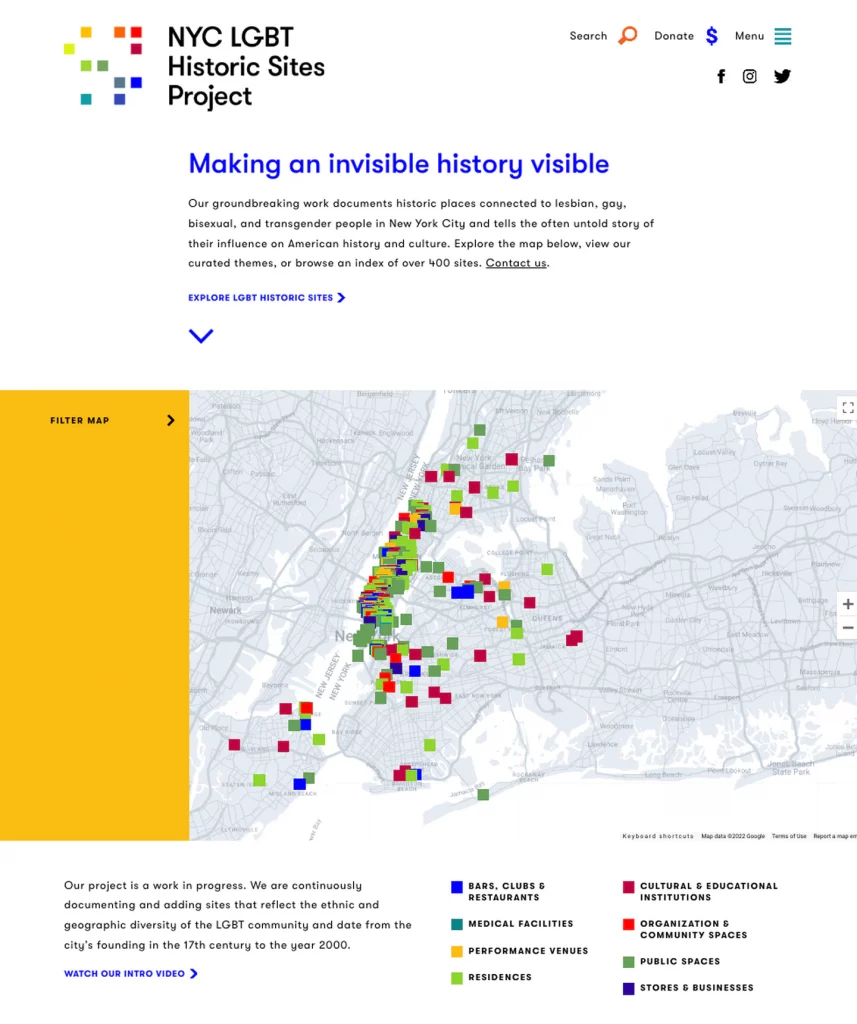

The first initiative to document historic and cultural sites associated with the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community in the five boroughs, the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project launched its website in March 2017, but the project is more than a quarter century in the making. Jay Shockley worked as senior historian at the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission, researching and writing over 100 designation reports covering all aspects of the city’s architectural, social, and cultural history, before turning his attention full-time to this project, which he directs together with Andrew Dolkart and Ken Lustbader. Related in certain ways to contemporaneous domestic and international efforts, the New York City project identifies and advocates for the preservation of LGBT historic sites in the city’s five boroughs, with a website featuring an interactive map of 111 sites and counting. Below, Shockley looks backward and forward, through the project and through his career, discussing the challenges that come with “making an invisible history visible.” – JM

Jacob Moore (JM): Tell me about the origins of the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project. Specifically, I’m hoping we might talk about what I see as the three different ways it engages with design and representation. Not only does it identify architectures and urban sites of significance, and employ techniques of representation for the organization and display of that information, but it also contends very directly with representation in a political sense. It clearly speaks to the way that political representation has changed from the 1960s to the present by engaging with historic sites themselves, reaching much further back in time.

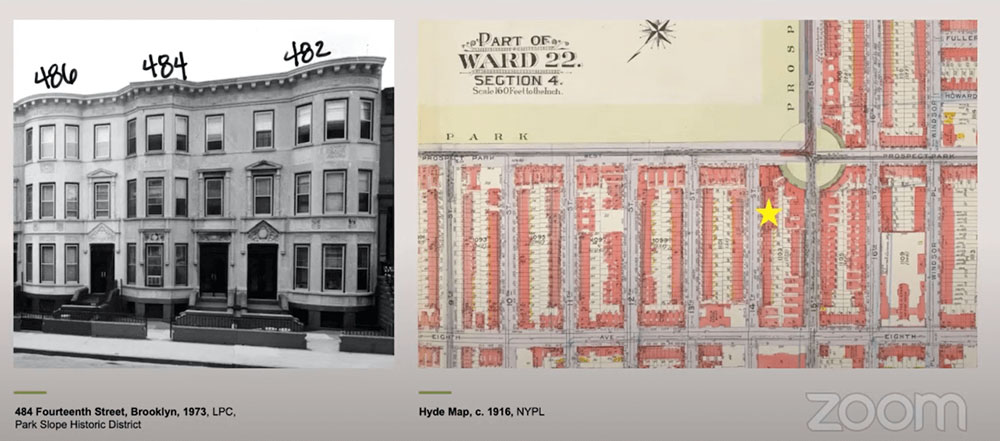

Jay Shockley (JS): Yes, our project pushes way beyond that. Our earliest site that we have currently online is from 1802. Also, it’s important to me to point out that the three of us who are the project, Andrew Dolkart, Ken Lustbader, and myself, are all historic preservationists, as is our project manager, Amanda Davis. So as a baseline we would absolutely say that this is architectural because the project is all site-based and every single story that we tell on the website — 111 so far — is architecture- and cultural heritage-based, unlike so many other projects that are online.

JM: Your point about it being rooted with a group of historic preservationists is really well taken, and I’m curious how your approach to that work has taken personal identity into consideration.

JS: I grew up in Baltimore and my family was Maryland-rooted on both sides for generations, with a real sense of place-based identity. It pained me that there were significant buildings, places that I loved, that were torn down. I went to Columbia, which is the first graduate program in historic preservation in the United States, for graduate school, and through a variety of circumstances, I got a part-time job at the Landmarks Commission and ended up being there for 35-and-a-half years. I worked on everything from 18th-century projects to World War II and everything in between. At a certain point, you realize there are all sorts of categories of buildings in New York — all sorts of categories of people — that are not getting addressed through historic preservation. One of the great ironies is that there’s a huge number of LGBT people that are in the design profession, in preservation in particular, but also cultural heritage, museum directors, museum curators, historians, professors, librarians, archivists … the number of LGBT professionals is just mind-blowing.

JM: Sort of an unspoken truth?

JS: Yes. At various points when I was working at the Commission, we were in the middle of the national culture wars and debates, with people like Jesse Helms and Strom Thurmond claiming that the LGBT community is destroying American culture when it was exactly the opposite. In many ways we’re both a creative force of American culture and we’re curators of that culture. So back in ’92, ’93, this organization called OLGAD (Organization of Lesbian + Gay Architects and Designers) briefly popped up. There were about a dozen of us historic preservationists who got together and produced a walking tour map in time for the 25th anniversary of the Stonewall Rebellion. One side was the Village, the other side was half Midtown and half Harlem. We now believe that was the first effort in the entire United States to do a site-based LGBT history. Andrew Dolkart and Ken Lustbader were part of that group, as was I. For almost the last 25 years we talked about doing something else, which ended up morphing into this project with a website.

In the meantime, despite the fact that New York has only one specifically designated landmark for LGBT purposes — Stonewall — the city has more LGBT documentation by far than any other city in the US due to staff efforts at the Commission. To New York’s shame, five other cities designated LGBT-associated buildings before we did, but then it finally came around in 2015 when Stonewall was made a city landmark. It was actually the week that marriage was legalized nationally; the Commission knew the Supreme Court decision was going to be coming out. They wanted to hop on the bandwagon.

Detail from “A Guide to Lesbian & Gay New York Historical Landmarks” (1994), published by the Organization of Lesbian + Gay Architects and Designers. Image courtesy of NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project

JM: Can you say more about how Stonewall led the way in terms of designation? And also about the need to expand the public’s understanding of LGBT spaces “beyond” Stonewall, as you state in the project’s mission?

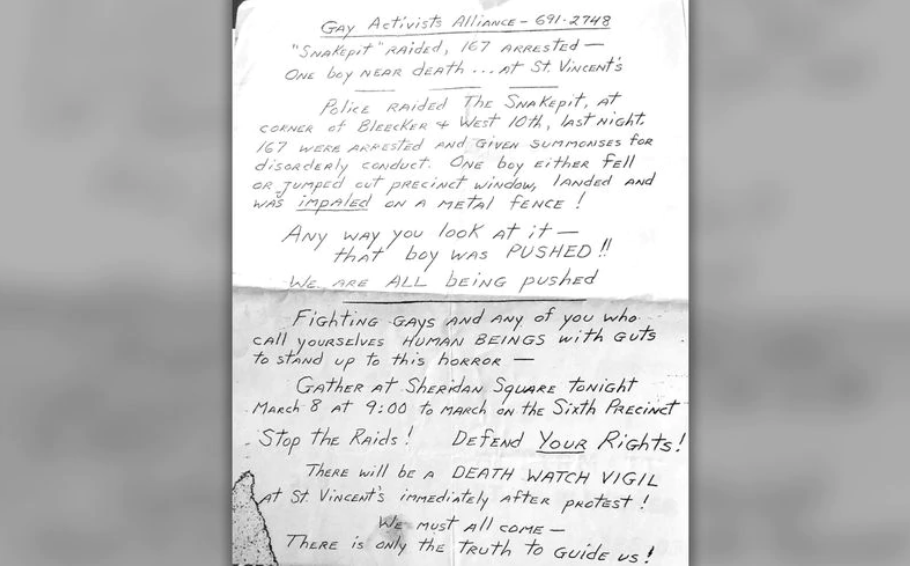

JS: As we were promoting this idea of LGBT place-based history, even with personal friends, even with other gay people, we’d always get this puzzled look, like, “What on earth are you talking about? What is there beyond bars?” So our motivation was to get this history out, as our tagline goes: making invisible history visible. It was to alert all the governmental decision-making bodies, like the Landmarks Commission, the New York State Preservation Office, much less the National Register of Historic Places, in part to destroy all these myths that history started at Stonewall. In our next round of sites, we’re going to include one 17th-century site of execution. There are two documented cases where men in New Amsterdam were killed for a charge of sodomy.

This map shows the 17th century Lower Manhattan waterfront, including the site at the intersection of Whitehall Street and the waterfront where men were executed for sodomy at least twice. Re-draft of the Castello Plan, New Amsterdam in 1660, drafted by John Wolcott Adams and Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes, 1916. Image via the New York Public Library, Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, courtesy of NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project

JM: Where did that happen?

JS: It was called “The Place of Executions.” It was the original southern shoreline of Manhattan at Whitehall. So we’re going to pin it on the map at about Whitehall and Water Street. They were outdoor executions. Another one was a known place that men looking for other men would go. In the 1840s, City Hall Park and the adjacent blocks of Broadway became notorious for young, working-class men selling their favors. Beyond this chronological diversity, I should also say that obviously the scope of our project is all five boroughs and the great diversity within the LGBT communities. We’re trying to destroy the myth that only Manhattan is where everything happened. But because our project is only extant sites, there are obviously a whole bunch of sites that just don’t exist anymore, which makes it challenging.

JM: What does that mean technically? For example, in the context of this execution place, what’s extant about it?

JS: Well, whatever they had at the time, whether it was a platform or whatever else, obviously doesn’t exist. But elsewhere we’re very much incorporating outdoor spaces, things like Central Park, so this felt just as legitimate. One thing that we originally thought we were going to exclude is the earliest gay rights outdoor protest that ever happened in New York. It was in front of the US Army Induction Center near Battery Park in Lower Manhattan in 1964. The building’s been torn down, but we’ve been rethinking it since the protest happened on the sidewalk in front of the building. That space still exists. That was such a significant event.

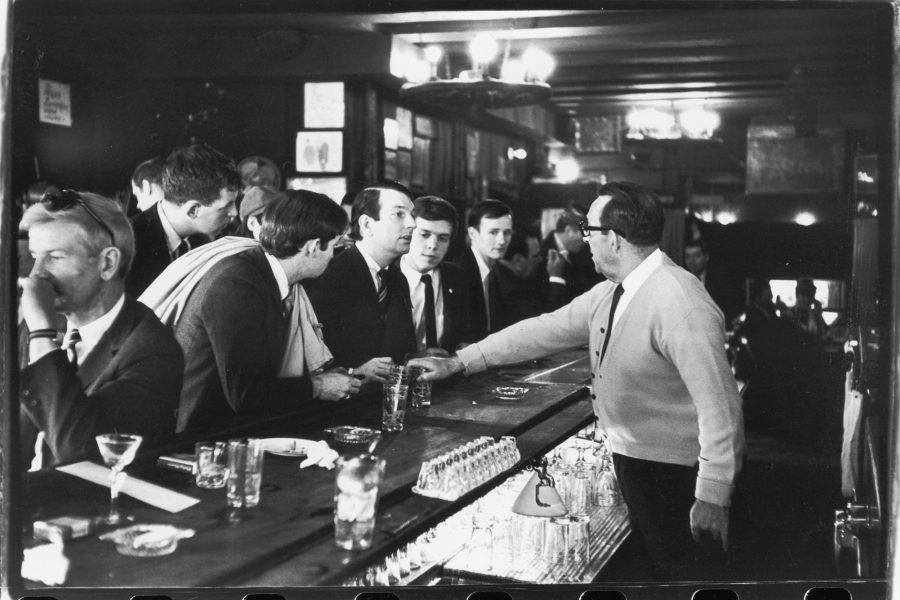

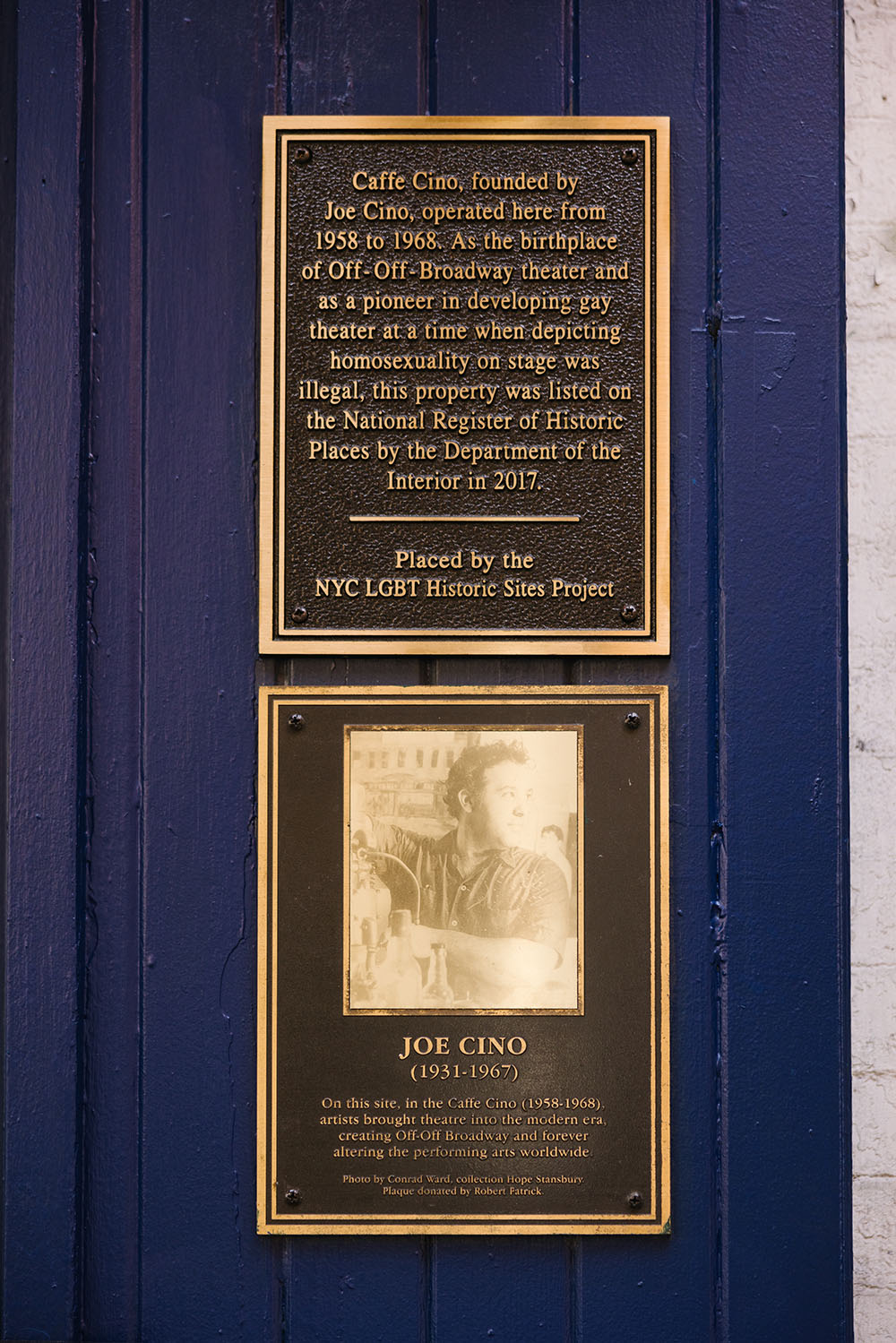

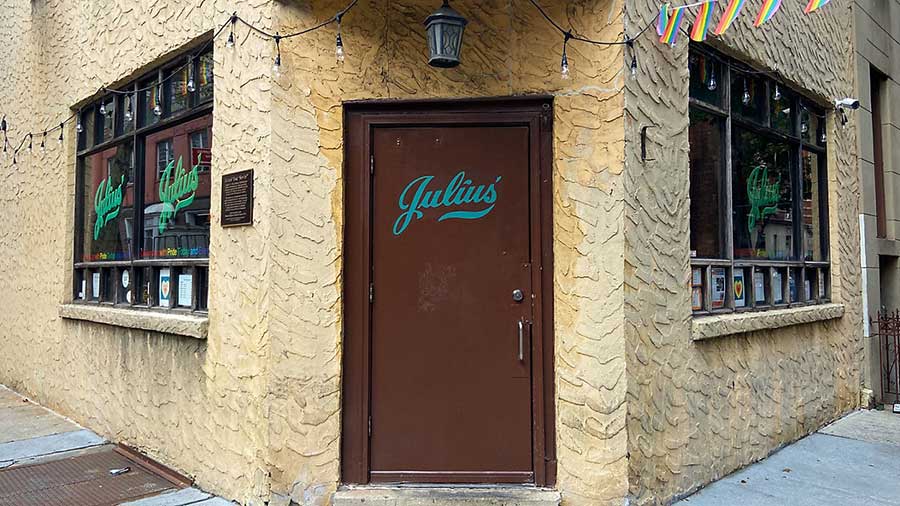

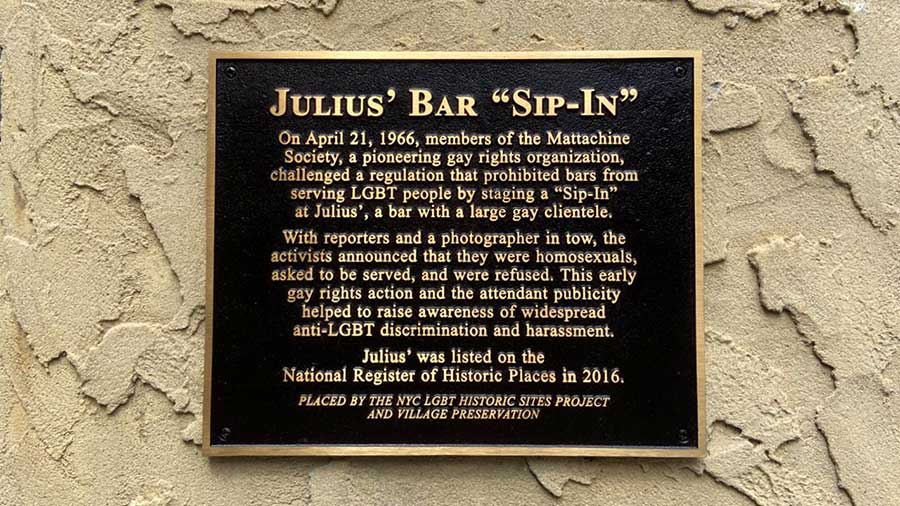

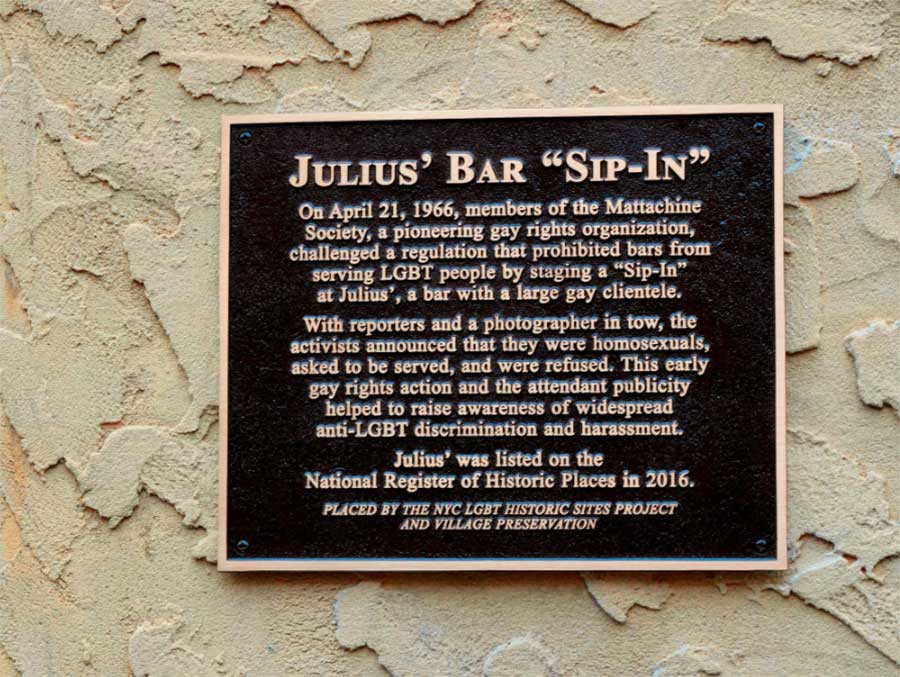

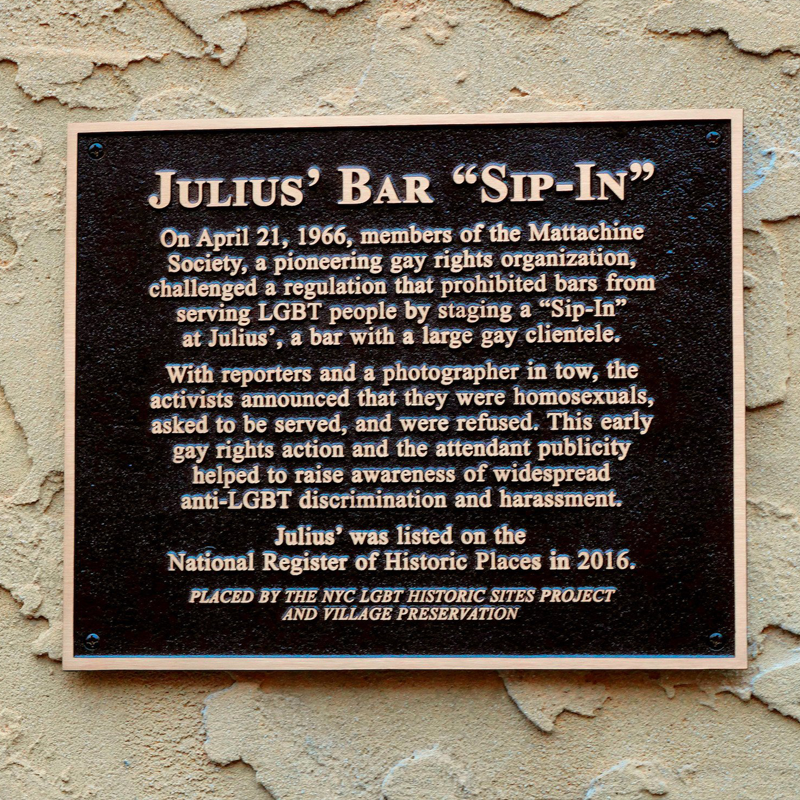

It was organized to protest the exclusion and discrimination of gay people in the military. Actually, our first accomplishment, before the website was launched, we got Julius’ Bar listed on the National Register of Historic Places literally one day before the 50th anniversary of the 1966 Sip-in. We specifically did that to show that there was a lot of activism pre-Stonewall. And that wasn’t even one of the earliest protests in New York. People picketed at the United Nations. The Mattachine Society’s Sip-in was probably the first thing that actually had a result because the state liquor authority, whose policies made it illegal to sell known homosexuals a drink, had to back away from enforcement because they got so much negative publicity. There was a psychiatrist speaking at Cooper Union about how gay people could be converted and so on and so forth in the early 60s, so there was a protest there that pre-dated the Sip-in.

Mattachine Society members John Timmons, Dick Leitsch, Craig Rodwell, and Randy Wicker being refused service by the bartender at Julius’, April 21, 1966. Photo by Fred W. McDarrah, courtesy of Estate of Fred W. McDarrah

JM: I’ve read that it’s a lot easier to get these places designated when you can point to other work, outside of preservation, that covers the topic. How does your work rely on or coordinate with history-writing more generally?

JS: It makes it easier if certain sites are discussed; the sad fact of the matter is that there’s very little LGBT history out there that’s site-based. Obviously there are things generally on personalities, biographies, general histories. Honing in specifically on Stonewall, at the same time that we published our map for OLGAD, we started a discussion at the National Park Service on having the site listed and we got back a response from the Department of the Interior that was very negative. Absent any other cultural context or precedent, it basically boiled down to: “Why is a ‘riot’ worthy of commemoration? If you people do something positive then maybe that should be commemorated instead.”

Participants of the Stonewall uprising in front of the bar, June 29, 1969. Photo by Fred W. McDarrah, courtesy of Estate of Fred W. McDarrah

JM: Wow. So this was in the early 1990s?

JS: That’s right. This is before a group of gay staffers at the Department of the Interior, including a gay Assistant Secretary of the Interior, helped push the nomination forward. Another issue was the fact that to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places you need owner consent, and the owners of the Stonewall were absolutely not interested. The two women considering the nomination at state level worked out an absolutely brilliant, unprecedented concept that allowed it to go forward. They said that if you include not just the Stonewall building but all the streets where the rebellion happened, it could be modeled after a Civil War battlefield, as an outdoor space. The side benefit is that the city of New York now had 50 percent ownership. It wasn’t just the owners of Stonewall. As long as you have 50 percent compliance in a situation like that, it can proceed. So that’s how Stonewall got listed. Thank god they kept it under the radar enough that there wasn’t any political opposition coming out of D.C. Stonewall was the first LGBT-related property listed on the National Register and it was fast-tracked the following year in 2000 to become the first LGBT National Historic Landmark, which is a rarefied subset of buildings that are on the National Register. Up until about three years ago, it was the only LGBT property.

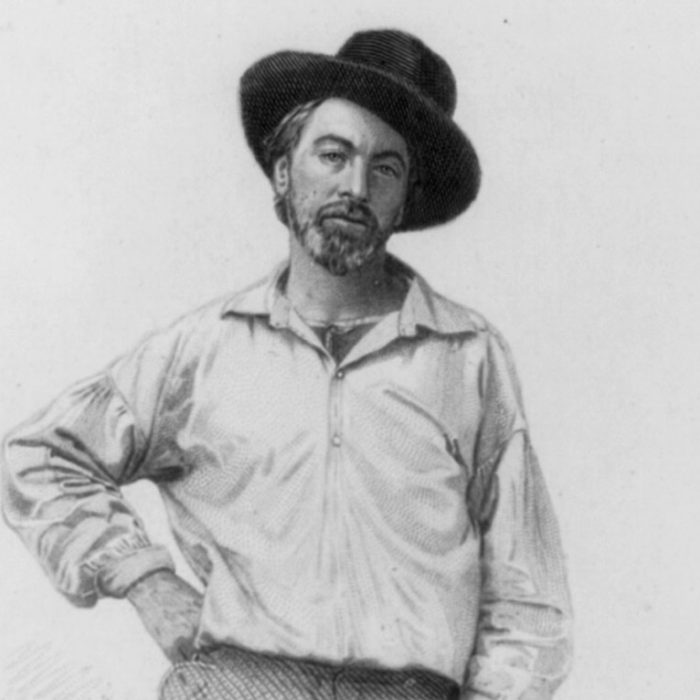

There are over 92,000 properties in the United States listed on the National Register. As we speak there are 16 LGBT-related properties nationally, out of 50 states. Pathetic. We have said for 25 years that if you really analyze the National Register, there are probably thousands of properties already listed that should be interpreted for LGBT history — things like Eleanor Roosevelt’s house at Hyde Park or Willa Cather’s house in Nebraska. None of those are documented or have any mention of the personal history of their occupants. Walt Whitman’s birthplace, his house in Camden, New Jersey — there are hundreds, if not thousands, of places on the National Register that need to be re-interpreted. Only in the last year or two is the National Register allowing that.

JM: That’s interesting that they’re now allowing reinterpretation of existing designations. How does that work?

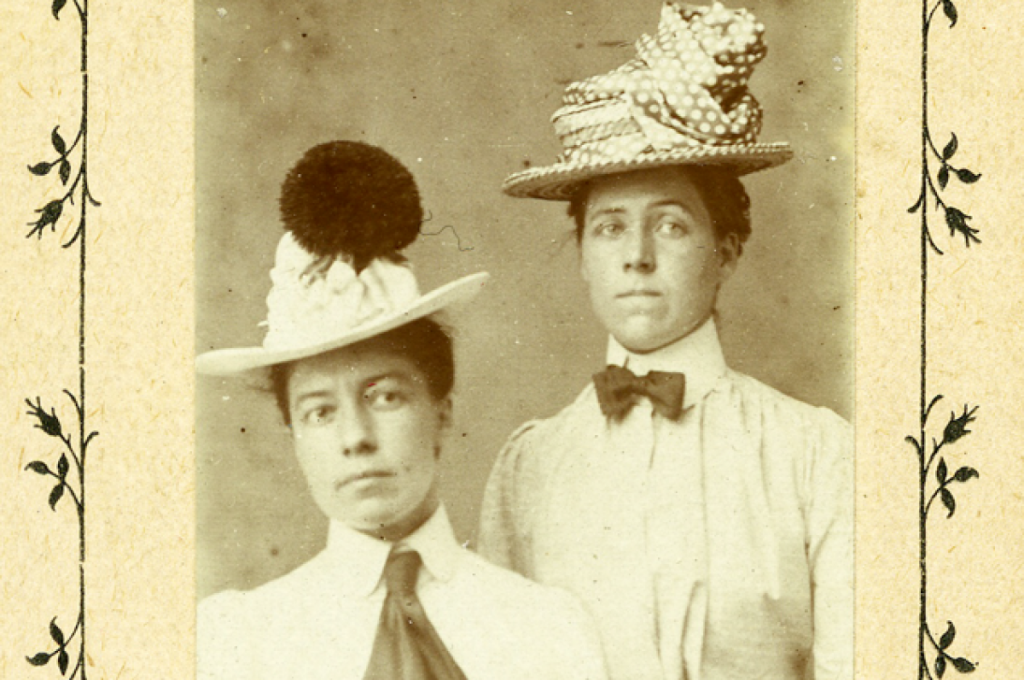

JS: You can now do a cultural overlay. We recently did a cultural overlay of the Alice Austen House in Staten Island. It was already listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and it is even a National Historic Landmark, but the original nomination never mentioned that she was a lesbian and had a 50-year relationship with another woman who lived with her, and it didn’t discuss her as a pioneering female photographer. So that’s what we did for that amendment.

The childhood home of pioneering female photographer Alice Austen, where she later lived with her partner of 53 years, Gertrude Tate. The site’s National Register of Historic Places nomination was amended in 2017 to include Austen and Tate’s relationship. Photo by Alice Austen via the New York Public Library Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy

JM: Who is the audience for this project? It’s very clearly about both places that are important for LGBT people as well as places made important by LGBT people.

JS: I’m glad you mentioned that, because we’re the first project in the United States, literally, that thought of it as two-fold. We very much wanted it focused on properties of import to the LGBT communities, but we also wanted to do the flip side, which is to highlight the impact we’ve had on American history and culture. When we first got funding from the National Park Service, I’m sure they didn’t realize that was the focus. Even people in the field of historic preservation or in governmental bodies that deal with such things assumed it would be the equivalent of the way Black civil rights sites have been traditionally designated.

During the height of the culture wars, Fran Lebowitz said, “If you removed all of the homosexuals and homosexual influence from what is generally regarded as American culture, you would pretty much be left with Let’s Make a Deal.” That is the crux of our project. In terms of constituencies, we are aiming at the LGBT community, but we’re also aiming at all the decision-making, governmental bodies. We want this to be a useful database for why properties are important and what properties are in what neighborhoods. We really want it to be used as an educational tool.

JM: Your essay for the National Park Service publication, LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History, discusses the Wilbraham, and in so doing paints the bachelor flat as a type that was leading your team to other sites of significance. Are there other specific examples where cultural heritage becomes represented by a particular architecture?

JS: We have found that there are several building types of significance, parallel to the Wilbraham but for a totally different class of men. Mills House on Bleecker Street was a philanthropic project where working class men could move to New York and stay out of evil boarding houses. But since they (there were several, actually) were built for 100 percent men, it was basically a wonderful place to introduce men coming to New York to gay life. That’s a parallel working-class example to the Wilbraham, which was for very upscale professional and upper-middle-class men. By the same token, the YMCA in Harlem played a very important role for LGBT black men coming to New York who had so few options for a place to stay, much less live for an indeterminate amount of time. The two YMCA buildings on 135th Street face each other — one was the older building and then it became so overcrowded they built what was then considered the country’s most state-of-the-art YMCA right across the street. A number of very prominent LGBT African-American men, including Langston Hughes, are known to have stayed there.

The Harlem YMCA Branch main building, located at West 135th Street, was constructed in 1932. Photo courtesy of University of Minnesota Libraries, Kautz Family YMCA Archives

JS: We have a few sites that were really important for casual meeting places. Stewart’s Cafeteria at Christopher Street and Seventh Avenue South was very popular in the 1930s. It was a late-night place. Cafeterias were places where those with very little money or no money at all could hang out. Horn and Hardart, the automat, fell in that category. There’s a surviving one up at Broadway and 104th Street. It’s a designated landmark I did the report for, a really beautiful polychrome terra cotta building.

JM: Can I ask — since I think it almost goes without saying what the urgency of a project like this is in a political context like the one we have today — what you think might be different about a project like this today, as opposed to if it had been possible to do something similar even 20 years ago?

JS: Wilbraham is a very good example. When I first wrote that, and I had the discussions of why that building type developed because of all the perceived gender threats of single men living in various places in New York by themselves, the then-chair of the Commission absolutely vetoed it. The first comment I got was, “no sex is allowed in our reports.” And it was nothing sexual! It was talking about gender roles and the directly related reason why these buildings were constructed.

JM: Beyond expanding the list, where does the project go from here?

JS: In the short term, we have obligations for a total of seven National Register properties to be listed, which is turning out to be really difficult. So many LGBT-related properties are not architecturally distinguished; it’s far easier dealing with high-style buildings by discernible architects. You still have negative perceptions of people who are building owners but who are not part of the community — who don’t want to be associated with the community — even through an honorary historic listing. The state of New York is requiring interior access and interior integrity, which is almost insurmountable. Then our current goal is just to keep the project constantly moving and getting more people aware of it and engaged with it, and we’re starting slowly to get nominations from the public.

JM: From the beginning you clearly knew that the website was going to be crucial. What sort of outreach was planned from the start and how much have you discovered after beginning? Was the role of social media always considered?

JS: We had wanted for 25 years to do something else, but we didn’t know exactly what, so we concocted that it’d be a website. We did not want a crowd-sourced project where anybody could pin whatever they wanted. We wanted this to be curated, for a variety of reasons. We didn’t just want people putting really personal stuff, like this is where I met my husband, or the first place I had sex. Nor did we want people putting homophobic stuff on it.

JM: How do you think of the acronym “LGBT”? Is there a Q? Have you come up against any challenges when trying to determine what’s in and what’s out?

JS: The project itself has some very defined boundaries. It’s just the city of New York. It’s just the five boroughs. To be listed on the National Register of Historic Places, there’s a 50-year timeline rule. So Stonewall had to reach way beyond that because it was only 30 when Stonewall was listed. We had to prove extraordinary importance. So we picked 2000 as our cut-off date into the future.

In terms of the naming of the project, the audience is LGBT and Q, but from a historical perspective we didn’t want to include the Q, since the sites are pre-2000. We’ve anticipated somebody questioning us not using the “Q” in the project name. We did it for a whole variety of reasons. You have to be aware that the use of “Q” was still very controversial and not standardized when the project began. The NYC LGBT Center on 13th Street has never officially incorporated Q into the name of the organization, for example. Terminology about sexuality and gender has continually evolved. Heterosexual and homosexual is late 19th century. Bisexual and transgender only started developing in the 20th century and have been used in different contexts for different things. Some people have said: “How can you call someone living in the mid-19th century a lesbian? That term didn’t exist then.” Terminology about gender and sexuality, as everything to do with the LGBT community’s history, is fraught. The more famous the person being labeled, the more controversial.

JM: Are there any sites for which the inclusion has given you pause, due to the possible controversy?

JS: If you look carefully at some of the things online on our website, we’ve purposely pushed a few buttons. But we’re not some sort of gossip site, casually mentioning things just because we want to. It’s all sourced and it’s all cited. People like Abraham Lincoln, Eleanor Roosevelt, Walt Whitman, Alexander Hamilton, we’ve not steered away from that at all. We’ve purposely included lots of sex sites and things that are sex-related. We’re not trying to steer out of any controversy at all. We want this to come across as relevant to the reality of the today’s America as we believe it is, controversy and all.

Jacob R. Moore is a critic, curator, and editor based in New York. His work has been exhibited internationally and published in various magazines and journals including Artforum, Future Anterior, and the Avery Review, where he is also a contributing editor.

Jay Shockley retired in 2015 as senior historian at the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission, where he had worked since 1979, during which time he helped pioneer the concept of recognizing LGBT place-based history by incorporating it into the Commission’s reports. He is a cofounder, together with Andrew S. Dolkart and Ken Lustbader, of the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project.

Click here to read the article on Urban Omnibus.com.

“This national award helps amplify the importance of documenting LGBT historic places and including these stories in the broader telling of American history. One of our Project’s most rewarding elements is connecting LGBT people around the world to their own history, much of which has long been hidden and intentionally erased. We hope this award encourages people to embrace LGBT history in their communities.” – Amanda Davis, manager of the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project

“This national award helps amplify the importance of documenting LGBT historic places and including these stories in the broader telling of American history. One of our Project’s most rewarding elements is connecting LGBT people around the world to their own history, much of which has long been hidden and intentionally erased. We hope this award encourages people to embrace LGBT history in their communities.” – Amanda Davis, manager of the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project

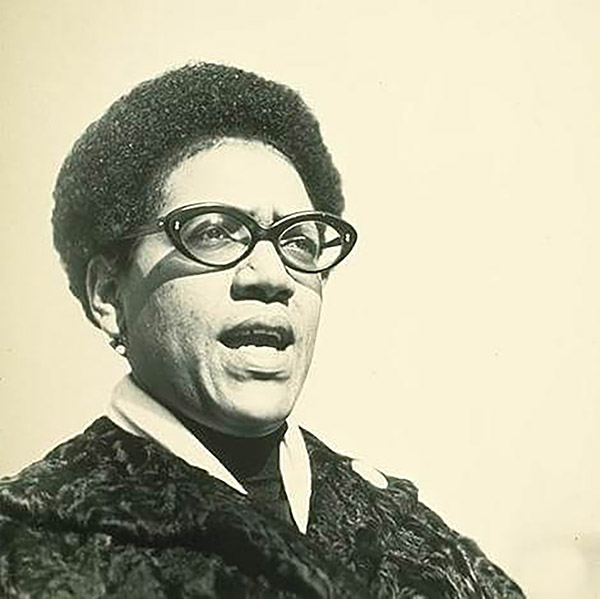

The former residence of Black lesbian playwright and activist

The former residence of Black lesbian playwright and activist  Renowned playwright and activist Lorraine Hansberry’s contributions to the arts will forever be embedded in the fabric of history and an effort to preserve a significant element of her journey has moved forward. According to Broadway World, the visionary’s former New York City residence has been added to the National Register of Historic Places.

Renowned playwright and activist Lorraine Hansberry’s contributions to the arts will forever be embedded in the fabric of history and an effort to preserve a significant element of her journey has moved forward. According to Broadway World, the visionary’s former New York City residence has been added to the National Register of Historic Places.

What new aspects of the project have developed over the past year?

What new aspects of the project have developed over the past year?

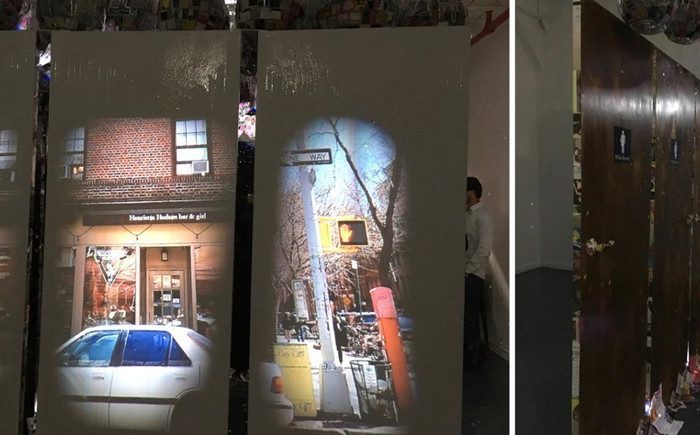

A historic New York building that was the meeting place of the Gay Liberation Front — once a leading gay rights organization, and the first in the nation formed after the Stonewall Riots — has been marked for destruction. As the planned demolition approaches, a group devoted to LGBTQ history is racing to document sites like it, before they disappear.

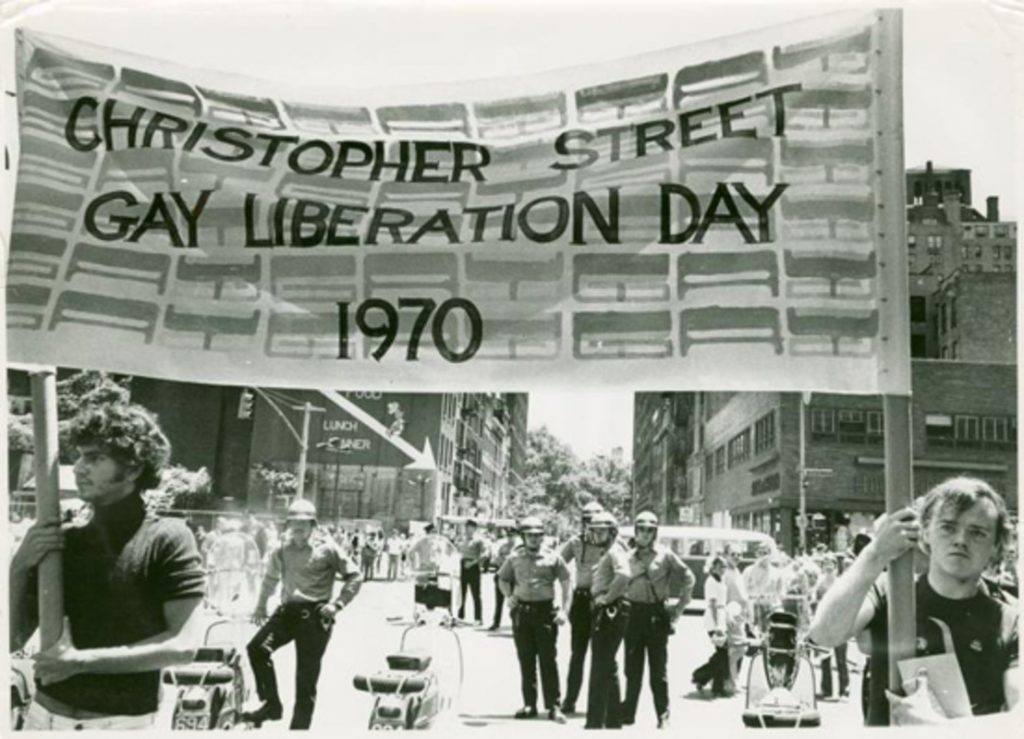

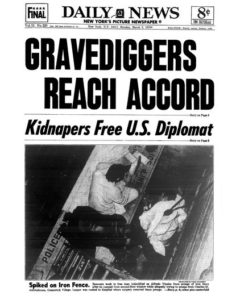

A historic New York building that was the meeting place of the Gay Liberation Front — once a leading gay rights organization, and the first in the nation formed after the Stonewall Riots — has been marked for destruction. As the planned demolition approaches, a group devoted to LGBTQ history is racing to document sites like it, before they disappear. The Gay Liberation Front (GLF) mobilized in 1969, after a police raid and subsequent riot at the Stonewall Inn. The structure, built in 1909, not only housed the group’s social and political gatherings, but was also the site of major cultural contributions to New York City and beyond, such as housing both the first Merce Cunningham studio and The Living Theatre, a venue that once hosted a reading by Frank O’Hara and Gregory Corso. (They were famously heckled by a drunk Jack Kerouac.)

The Gay Liberation Front (GLF) mobilized in 1969, after a police raid and subsequent riot at the Stonewall Inn. The structure, built in 1909, not only housed the group’s social and political gatherings, but was also the site of major cultural contributions to New York City and beyond, such as housing both the first Merce Cunningham studio and The Living Theatre, a venue that once hosted a reading by Frank O’Hara and Gregory Corso. (They were famously heckled by a drunk Jack Kerouac.) The planned demolition “is a real loss that shows the significance of LGBT spaces and cultural sites in the city should be recognized,” Ken Lustbader, a co-founder of the New York City LGBT Historic Sites Project told Hyperallergic. “We’re trying to get ahead of the curve proactively to identify these sites that show and convey LGBT history.”

The planned demolition “is a real loss that shows the significance of LGBT spaces and cultural sites in the city should be recognized,” Ken Lustbader, a co-founder of the New York City LGBT Historic Sites Project told Hyperallergic. “We’re trying to get ahead of the curve proactively to identify these sites that show and convey LGBT history.” This is first time in the four-year history of the organization that a site is actively being threatened with demolition. The threat of losing such an important piece of queer history underscores the urgency of the organization’s work: to document neglected, forgotten, and vanishing sites that shaped LGBTQ communities and American culture.

This is first time in the four-year history of the organization that a site is actively being threatened with demolition. The threat of losing such an important piece of queer history underscores the urgency of the organization’s work: to document neglected, forgotten, and vanishing sites that shaped LGBTQ communities and American culture. For the organization’s founders, the importance of national history is matched by an awareness of local transformation. Lustbader and Shockley live blocks away from the GLF’s former meeting site. “There’s been increasing discussion over the last year about all new developments on 14th Street,” Shockley said, describing another planned demolition at an adjacent site. The 1952 building where Banksy recently drew his now-famous rat sold last year, for $42.4 million, is set to be torn down to make room for a condominium and retail space. That building also had a 110-foot-long mural in its lobby: Julien Binford’s “A Memory of 14th Street and 6th Avenue.” If it weren’t for the joint efforts of New York City Council Speaker Corey Johnson and the community-based preservation group Save Chelsea, that too, would’ve been destroyed forever. “14th Street, like every place else in Manhattan, is getting attacked by high rise development,” Shockley said.

For the organization’s founders, the importance of national history is matched by an awareness of local transformation. Lustbader and Shockley live blocks away from the GLF’s former meeting site. “There’s been increasing discussion over the last year about all new developments on 14th Street,” Shockley said, describing another planned demolition at an adjacent site. The 1952 building where Banksy recently drew his now-famous rat sold last year, for $42.4 million, is set to be torn down to make room for a condominium and retail space. That building also had a 110-foot-long mural in its lobby: Julien Binford’s “A Memory of 14th Street and 6th Avenue.” If it weren’t for the joint efforts of New York City Council Speaker Corey Johnson and the community-based preservation group Save Chelsea, that too, would’ve been destroyed forever. “14th Street, like every place else in Manhattan, is getting attacked by high rise development,” Shockley said.