Month: November 2022

Walkers in the City

November 27, 2022

By: Robert Sullivan

At the outset of the Covid-19 lockdown, Michael Kimmelman, the New York Times architecture critic, invited various architects, urban planners, writers and other experts to suggest walking tours of New York City, hoping that the itineraries would offer “examples of how the city remains beautiful, inspiring, uplifting.” Within days, the first account of what would ultimately be 17 walks was published, a conversation between a critic and a thinker, set within a particular area of the city. Now those walks, plus three more, have been assembled into a collection, “The Intimate City,” each chapter a geographic memoir: streetscape-jogged annotations on history, infrastructure, planning and combinations thereof, complemented by photos, many from the original series. “I was on the lookout,” Kimmelman says in his introduction, “for stories, both intimate and about the city, that I thought seasoned, savvy New Yorkers might find surprising — tidbits of history, law, technology or gossip I hadn’t heard myself, or that revealed something about the people who were telling the stories.”

“The Intimate City” is a joyful miscellany of people seeing things in the urban landscape, the streets alive with remembrances and ideas even when those streets are relatively empty of people. Thomas J. Campanella, a professor of city planning at Cornell, points out the spot in Brooklyn Heights where W.H. Auden, Benjamin Britten, Carson McCullers and Gypsy Rose Lee lived in the 1940s, before the house was demolished to make way for the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. Guy Nordenson, the renowned structural engineer, notes the enormous pendulum dampers inside 432 Park Avenue, an 85-story pencil tower: The pendulums soften the force of the wind that causes the stacked luxury condos to sway. The writer Daniel Okrent reminds us that before “Saturday Night Live” broadcast from Rockefeller Center, the developers piped in laughing gas to a floor of one building in the complex, hoping to lure dentists.

In many of Kimmelman’s conversations, architecture refers less to the design of buildings than to how built spaces are used. When David Adjaye, the Harlem-based architect who designed the Studio Museum, passes the front of the Hotel Theresa, he pictures the guests interacting outside: Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first president, chatting with Malcolm X and Adam Clayton Powell Jr. “It was another Speakers’ Corner,” Adjaye says. Kate Orff, whose landscape architecture firm, SCAPE, designed a wave-reducing oyster reef now being implemented off Staten Island, as well as green space for Amazon’s new Virginia headquarters, toured her Queens neighborhood with Kimmelman, saying, “For me, Forest Hills doesn’t feel like a housing development as much as it feels like a landscape with housing in it.”

Kimmelman’s own recollections of growing up in Greenwich Village dovetail with the historical insights of Andrew Dolkart, an architectural historian and the co-founder of the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, which aims to increase public awareness of local sites important to L.G.B.T.Q. history. When activists applied to have the Stonewall Inn listed on the National Register, Dolkart reports, they sought the designation for adjoining streets — which also figured in the 1969 uprising for L.G.B.T.Q. rights — at the same time, and were advised to follow guidelines for registering Civil War battlefields.

Though “The Intimate City” visits four of the five boroughs (it skips Staten Island), it is centered on Manhattan. It refers to Native Americans only as the earliest residents of Manhattan, despite the fact that Native American construction workers helped build both World Trade Centers and vast swaths of the modern skyline. A walk through the Bronx that was not featured in The Times is led by Monxo López, the co-founder of the Mott Haven-Port Morris Community Land Stewards, a community land trust. Amid all the lockdown-era enthusiasm about New York’s resilience — “I suspected, no matter what misery was coming, that the city would endure and even prosper,” Kimmelman recalls — López’s view of his community’s future is practical. His organization seeks to remove lots from the speculative real estate market, so that the neighborhood’s residents can retain a stake in its development. “The Bronx is not about consumption,” says López. “It’s about community.”

Covid’s devastating impact in the area of López’s tour suggests that New York City didn’t just come back; it never stopped being what it was, and, in the process, the most vulnerable died or became more vulnerable. The pandemic — with its quickly constructed hospitals, neighborhood-level mutual aid, and relief (if temporary) for rising rents — showed us another way to build the city in the future.

Robert Sullivan is a contributing editor at A Public Space, and has just completed a book on 19th-century Western survey photography.

Brooklyn Gets First LGBTQ+ Landmark With Designation of Lesbian Herstory Archives

November 22, 2022

By: Anna Bradley-Smith

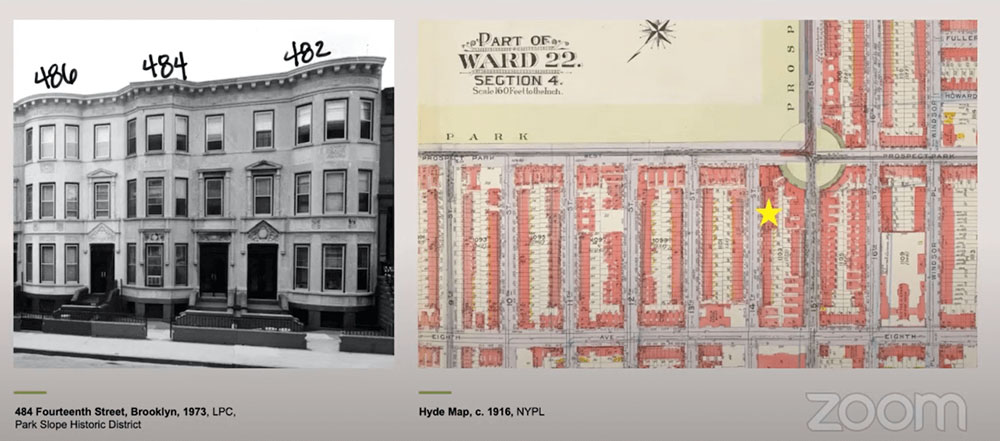

Commissioners on the city’s Landmark Preservation Commission unanimously voted to landmark the Park Slope headquarters of the Lesbian Herstory Archives in a public meeting today.

The vote followed an October 25 public hearing where six people testified in support of landmarking the building at 484 14th Street due to its cultural significance. “Most lesbians don’t inherit queer culture from our parents, the Lesbian Herstory archives is our birthright and it’s the place where we can go to learn our own history,” LHA coordinating committee member Colette Denali Montoya-Sloan told commissioners at the hearing.

She added that the building, owned outright by the nonprofit, is “intricately linked to lesbian life in New York City as the archival home of anyone who identifies as a former or current lesbian, or in any way with the word,” and said all are welcome to visit and research, not just lesbians. LPC also received 34 letters in support of designation.

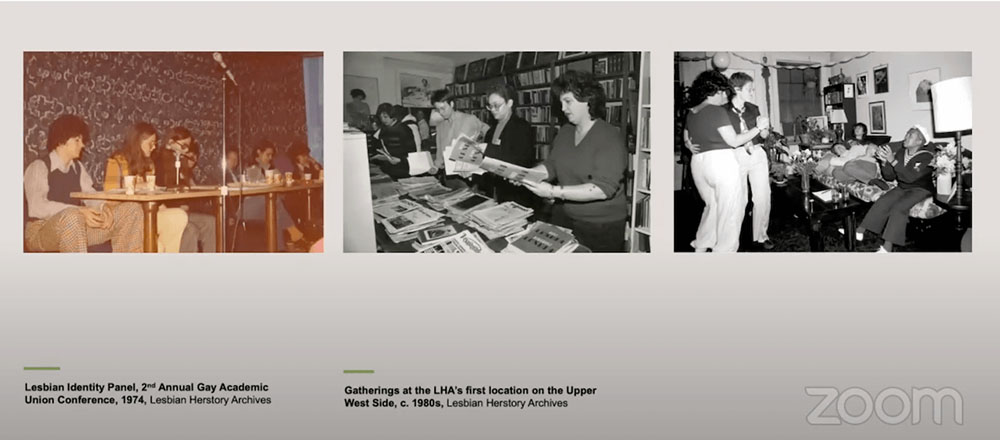

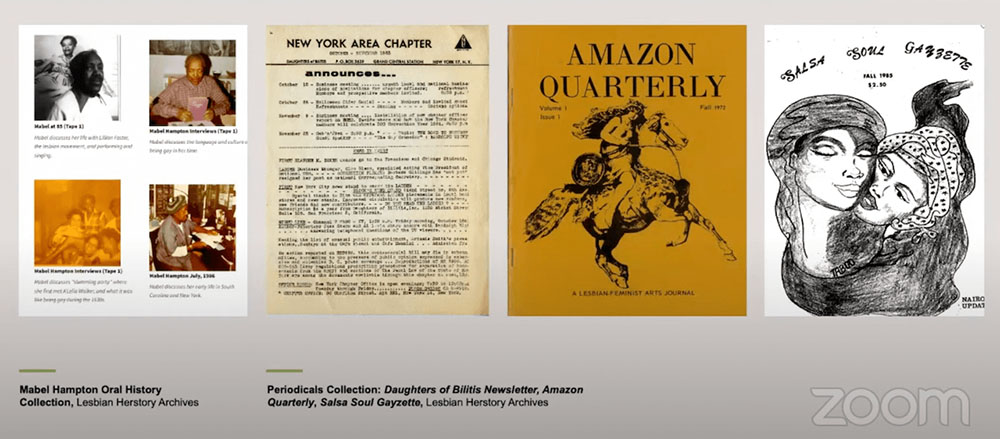

LPC Deputy Director of Research Margaret Herman told commissioners the house is culturally significant as the home of the archives since 1991, “the nation’s oldest and largest collection of lesbian related historical material,” which was founded out of an Upper West Side apartment in 1974 by lesbian activists.

For the past 30 years, the 1908 Axel Hedman-designed Park Slope house has been “a permanent headquarters that can serve as a direct response to the pervasive homophobia, sexism and lack of lesbian space that community had experienced throughout history,” Herman said.

The house already sits within Park Slope’s historic district, but given the district’s 1973 designation predated the arrival of the organization there’s no mention of the building’s LGBTQ+ significance in city records. Designating it an individual landmark would allow for that recognition.

LPC Deputy Director of Research Margaret Herman told commissioners the house is culturally significant as the home of the archives since 1991, “the nation’s oldest and largest collection of lesbian related historical material,” which was founded out of an Upper West Side apartment in 1974 by lesbian activists.

For the past 30 years, the 1908 Axel Hedman-designed Park Slope house has been “a permanent headquarters that can serve as a direct response to the pervasive homophobia, sexism and lack of lesbian space that community had experienced throughout history,” Herman said.

The house already sits within Park Slope’s historic district, but given the district’s 1973 designation predated the arrival of the organization there’s no mention of the building’s LGBTQ+ significance in city records. Designating it an individual landmark would allow for that recognition.

LPC Chair Sarah Carroll said the designation would reflect an important layer of history, “but have a more subtle regulatory impact” given it is in the same architectural style as the rest of the historic district and already abides by those rules. She said Lesbian Herstory Archives could install a plaque if they wished, something she signaled support for.

“I’m really thrilled that we are voting on this building today. The Lesbian Herstory Archives is a nationally important organization and collection of LGBTQ+ historic materials and it’s really played an essential role in preserving and telling the most mostly unseen stories of a community of women, including many who have contributed to America’s cultural, political and social history,” Carroll said.

“The Archives has made this row its home for over 30 years for 30 years and it’s long association and stewardship of the building have added this layer, and so while there may not be architectural changes that speak to it, I think that our designation will really highlight and celebrate this sort of layer, very significant layer, of the building and I’m delighted that our vote and on this designation draws attention to the importance of lesbian Herstory archives to New York City’s history and the country’s history and the LGBTQ+ community.”

Commissioner Michael Goldblum said the designation was “one of a series of really important designations” Carroll had led the way on “that relate to the cultural history of New York City, and its various communities over the last couple of years.” He said he thought there were likely many other culturally significant buildings in the city that deserve this kind of “recognition and thoughtful designation.”

Commissioner Fred Bland added that LHA’s designation “is right in line with our society and its movements” and said it was critical that preservation keep up with societal movements.

“I have warned a little bit in the past that we’ve got to be careful about cultural designations because after all this is New York City, every block has some interesting thing that happened on it, you know, and we have to be careful about those cultural significant happenings, but somehow this one is so obvious it’s hard to put into words why this is so appropriate, and maybe other kinds of cultural designations might not be so obvious. This one is just so obvious.”

In a press release, project manager of the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project Amanda Davis said the group was thrilled the women-owned building was now officially recognized as a New York City landmark, “further solidifying the importance of including LGBTQ history in the broader narrative of American history.”

“The designation — the first for an LGBTQ site in Brooklyn — acknowledges the pioneering lesbian women who, nearly 50 years ago, came together to create an affirming space for their community. Perhaps most significantly, these women reclaimed their past by saving and preserving lesbian-related records, photographs and ephemera for future generations of queer women,” Davis said.

WATCH: NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project Receives Prestigious Trustees’ Award from the National Trust for Historic Preservation

November 5, 2022

The NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project is thrilled and honored to share that our work to identify and document NYC’s place-based LGBT history was honored by the National Trust for Historic Preservation Friday, November 4th, with their Trustees’ Award for Organizational Excellence, one of our field’s highest honors. The award was given at the PastForward Conference, in a ceremony hosted by old house icon Bob Vila.

The NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project is thrilled and honored to share that our work to identify and document NYC’s place-based LGBT history was honored by the National Trust for Historic Preservation Friday, November 4th, with their Trustees’ Award for Organizational Excellence, one of our field’s highest honors. The award was given at the PastForward Conference, in a ceremony hosted by old house icon Bob Vila.

“Each year at the PastForward Conference we come together to recognize those making a real difference in historic preservation. This year’s recipients embody not just the preservation of American history, but also demonstrate how preserving historic places can play a key role in addressing critical issues of today, including climate change, equality, and housing.” — Paul Edmondson, president and CEO of the National Trust for Historic Preservation

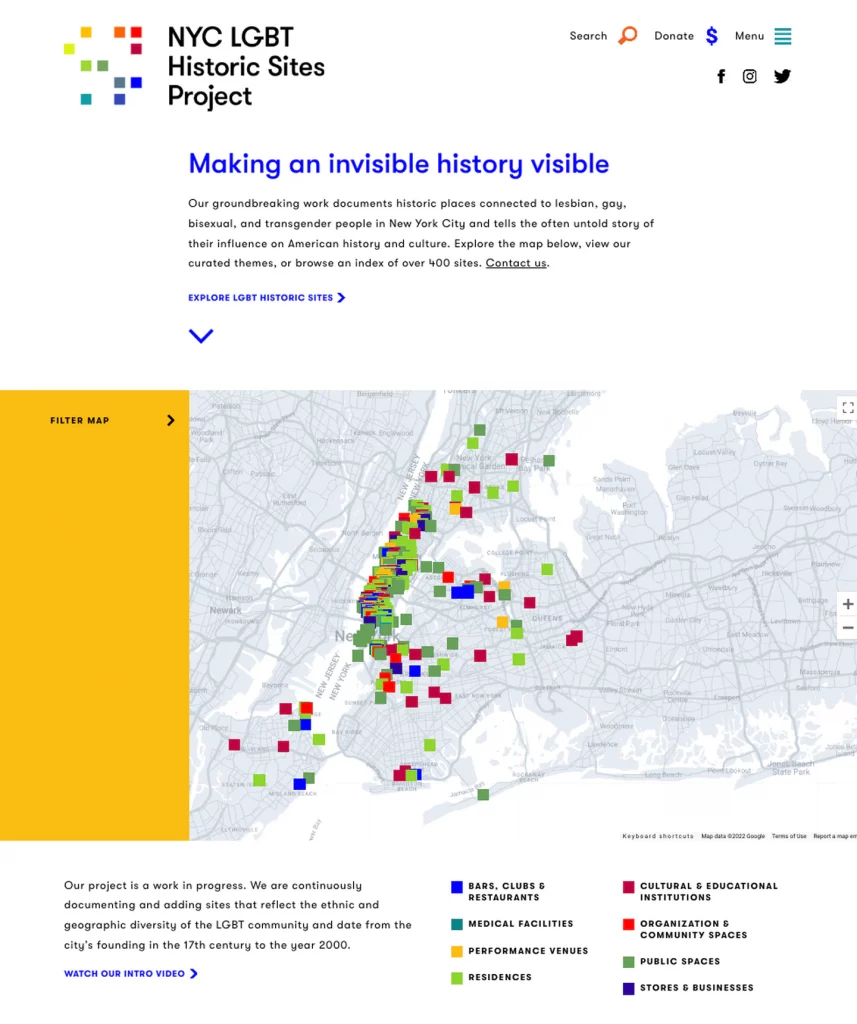

Since its founding in 2015, the Project has now identified, researched and mapped over 400 sites across New York City’s five boroughs which connect the public viscerally to the places — residences, bars and venues, public spaces, and more — where LGBT people have contributed to American culture.

About the Trust’s selection of the Project for the 2022 Trustees’ Award for Organizational Excellence: The NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project is a nationally-recognized and influential cultural heritage initiative and educational resource that identifies and documents diverse extant LGBT sites from the 17th century to 2000. The only permanent organization of its kind in the US, the project staff have created an interactive website, National Register nominations, publications and public programs, and school educational materials, among other resources. Sitting at the intersection of historic preservation and social justice, the organization has been particularly eager to document LGBT sites associated with women and Black, Asian, Latinx, trans, and gender-variant communities. In the near future, they hope to prioritize local sites of LGBT history associated with Indigenous and Two Spirit Peoples.

Landmarks Holds Public Hearing for Julius’ Bar

November 21, 2022

By: Cassidy Strong

Located at the corner of West 10th Street and Waverly Place, Julius’ holds great significance in NYC’s LGBTQ+ history and is undergoing Individual Landmark consideration. On November 15, 2022, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing to discuss landmarking Julius’ Bar, located at 159 West 10th Street in Manhattan. The building was previously calendared for Individual Landmark consideration on September 13.

The public hearing began with a presentation from Kate Lemos McHale, Landmarks’ Director of Research. McHale described Julius’ Bar as “New York City’s most significant site of pre-Stonewall LGBTQ activism.” In 1966, three years before the Stonewall Rebellion, four activists with the Mattachine Society held a “Sip-In” at Julius’ Bar to protest the closure of restaurants and bars serving queer people. Modeling this direct action after the Civil Rights Movement, the Sip-In showcased the frustration and bold ideas of NYC’s gay community years before the Gay Liberation Movement.

McHale also shared that Julius’ Bar is located in the Greenwich Village Historic District, only a few minutes’ walk away from the Stonewall Inn. Stonewall was designated as an Individual Landmark in 2015, and by doing the same with Julius’ Bar, the building’s importance in the fight for LGBTQ+ rights would be specifically honored.

While the building dates back to 1826, Julius’ Bar opened as a speakeasy in 1930. It quickly became a hub for artists and writers, with the Village Voice launching there in 1955. As queer New Yorkers migrated towards Christopher Street in the 1950s and 60s, when post-WWII discrimination was at an all-time high, Julius’ Bar was home to both gay and straight patrons. In NYC, gay men were criminalized, while the NYS liquor authority revoked licenses for places serving gay people. By bringing a photographer to Julius’ Bar and stating they were gay, leading the bartender to refuse service, members of the Mattachine Society were able to document anti-LGBTQ discrimination in mainstream media for the first time. Today, the building has the same appearance it did during its period of significance and is widely recognized for this activism.

Following McHale’s presentation, the Landmarks Commissioners had no additional questions, so Chair Sarah Carroll opened up the hearing for public testimony. Helen Buford, owner of Julius’ Bar for the last 13 years, began the testimony period by voicing her support for the landmarking, again highlighting the Sip-In event, and thanking regular customers for their support.

Buford was followed by Randy Wicker, a Mattachine Society member and witness to the Sip-In. Wicker explained that Julius’ Bar was a neighborhood staple where many customers happened to be gay. In order to avoid plainclothes police, the bar adhered to strict rules, like only admitting men on weekends if they had women as dates. Wicker emphasized that because Julius’ Bar agreed to be targeted by the Mattachine Society, gay people were given the “constitutional right to public assembly and accommodation.”

Andrew Dolkart, a historic preservation professor, spoke next on behalf of the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project. Dolkart shared that the Project “strongly supports” landmarking Julius’ Bar, which is often the last stop on their walking tours of queer historic sites, and that their research led to Julius’ being listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2016.

Following Dolkart’s testimony, NYS Assemblymember Deborah Glick also spoke in favor on behalf of herself and NYS Senator Brad Hoylman. Both Dolkart and Glick praised Helen Buford’s ownership and emphasized the Sip-In’s historical importance, with Assemblymember Glick stating: “The significance of the event warrants the acknowledgment and designation of Julius’ as a landmark, and would demonstrate the City’s commitment to ensuring that the history of the fight for LGBTQ rights is commemorated.” Glick explained that both her and Hoylman are members of the LGBTQ+ community, and thanked Landmarks for their efforts to designate queer sites.

Assemblymember Glick was followed by Andrew Berman, executive director of Village Preservation. Berman explained that nine years ago, Village Preservation called for Julius’ Bar to be designated as an Individual Landmark alongside three other sites. While the other buildings have since been landmarked, Village Preservation has continued to urge Landmarks to designate Julius’ Bar. Next, Brad Vogel spoke on behalf of the Walt Whitman Initiative, stating that Julius’ continues to be a safe haven for the LGBTQ+ community. The Initiative strongly supports this designation, Vogel explained, because other pre-Stonewall historic sites are similarly worthy of consideration, namely Whitman’s Leaves of Grass House.

Others who spoke in support included Lucie Levine of the Historic Districts Council, curator and Greenwich Village native Steve Jaffe, and Brendan Byrnes, who married his husband at Julius’ Bar in 2014. City Councilmember Erik Bottcher had also signed up to speak, but was unable to attend the public hearing.

Chair Carroll closed the public hearing by thanking everyone for their testimony, stating that she was “delighted to be moving forward” with Julius’ Individual Landmark designation. Carroll also shared that Landmarks will hold a final public meeting on Julius’ Bar “in the very near future, when [Landmarks] can schedule a vote.”

By: Cassidy Strong (Cassidy is a CityLaw intern and a New York Law School student, Class of 2024.)

LPC: Julius’ Bar Building, LP-2663. November 15, 2022.

Greenwich Village, Storied Home of Bohemia and Gay History

November 21, 2022

By: Michael Kimmelman

The architectural historian Andrew Dolkart leads a walk past landmarks like the Stonewall Inn, Julius’ bar and the home of Lorraine Hansberry.

(this article was excerpted from Kimmelman’s new book, “The Intimate City: Walking New York.”)

Credit: Michael Evans / The New York Times

The fountainhead of American bohemia, Greenwich Village has always departed from the straight and narrow. Its entanglements of winding streets, defying the city grid, include remnants of cow paths and property lines from when the area was a sprawl of Dutch, then English, farms.

The Village as a historically gay neighborhood has long been a source of local pride, but it seemed mostly unremarkable to me and to my childhood friends who were native Villagers because it was simply another fact of daily life. Long before our time, Macdougal Street had been an early hub for L.G.B.T.Q. clubs and tearooms like the Black Rabbit. By the 1970s, the neighborhood’s gay epicenter had shifted toward Christopher Street, the oldest street in the Village, its irregular route tracing the border of what had been the British admiral Peter Warren’s Colonial-era estate.

Not long ago I asked Andrew Dolkart, an architectural historian at Columbia University, to construct an L.G.B.T.Q. tour of the Village. Dolkart is a co-founder of the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project and a co-author of the nomination for Stonewall to the National Register of Historic Places. What follows is an edited excerpt of our conversation, which appears in my new book, “The Intimate City: Walking New York.” The book grew out of walks I organized across the city with various architects, historians and others during the early months of Covid-19, a number of which were published by The Times. This Village walk was one of several written for the book.

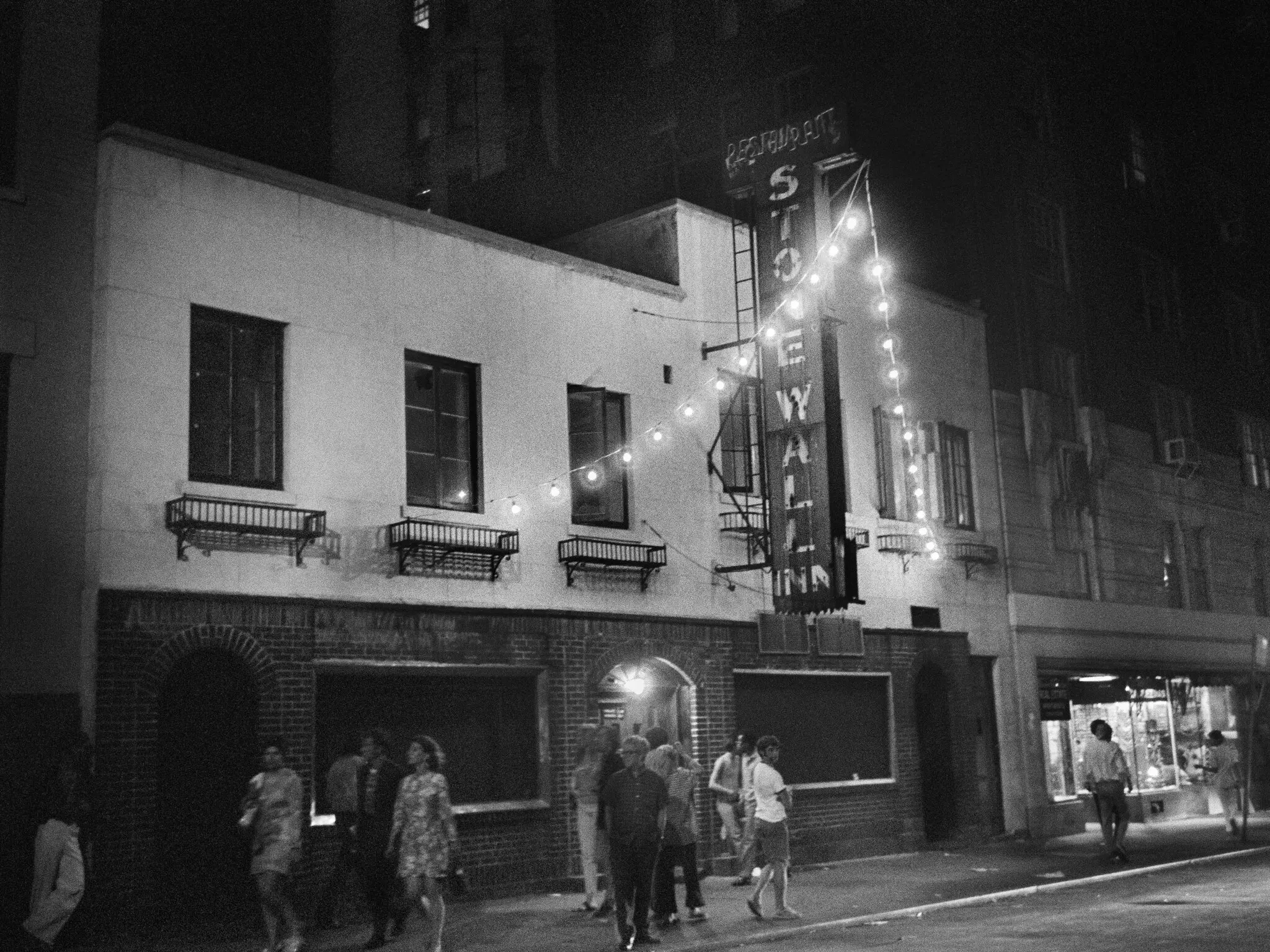

MICHAEL KIMMELMAN Andrew, during the summer of 1969, police raided a bar at 51-53 Christopher Street called the Stonewall Inn.

ANDREW DOLKART In the 1960s, the Stonewall Inn was a Mafia-controlled bar, as were almost all gay and lesbian bars, because the State Liquor Authority decreed that the mere presence of a homosexual in a bar constituted disorderly conduct. The Mafia ran these bars and paid off the police. But there were still raids every now and then. In June of 1969, there was one on Stonewall. Usually with these raids the police arrested a few people, everybody left and things went back to normal. But in this case, the patrons of the bar fought back and a crowd developed outside. People started throwing things. Some police eventually had to barricade themselves in the bar. Demonstrations continued for several nights. The authorities didn’t really know how to handle the situation.

Why there and then?

There had been earlier incidents in San Francisco and Los Angeles, where L.G.B.T.Q. people fought back. They were clearly fed up and saw all of these other liberation movements in the country gaining traction — women’s liberation, civil rights, the antiwar protests. David Carter, who wrote a book about Stonewall and helped us get Stonewall on the National Register, pointed out that the police tactical group that raided the bar that night was not familiar with the layout of Greenwich Village, and so when officers tried to clear the crowd, the crowd simply ran down all these irregular streets and circled right back, which kept the action going. That’s why the National Register listing includes the Stonewall building, Christopher Park, and all of the streets around it, as far east as Sixth Avenue.

The register in a sense nods to the Village at large as a gay haven.

Its gay history goes back at least to the early 20th century, when Greenwich Village was becoming a bohemian capital. Back then, there were lots of unmarried people living together in the Village, which made it attractive to same-sex couples because they could live more openly.

Was there something distinct about the architecture or the physical layout of the Village that attracted outliers?

The Village’s housing stock was a big factor. We now think of multimillion-dollar sales of old rowhouses in the Village, so it’s hard for some people to imagine that the Village used to be cheap and rundown. Those old rowhouses were not always beloved, and a lot of them were subdivided into cold-water flats or had become rooming houses. The associated low rents, of course, are why the bohemians initially gravitated to Greenwich Village.

For the same reasons, the Village also became a magnet for immigrants and working people escaping disease and overcrowding in Lower Manhattan.

You can still see some of these early houses on streets like Grove and Bedford, where affluent people moved during the early 19th century after outbreaks of malaria and yellow fever farther downtown. Then came waves of development in the 1830s and ’40s, and with it, increasing class stratification. Fifth Avenue and the northern side of Washington Square become prestigious. Then houses become increasingly more modest as you approach the Hudson River waterfront.

The waterfront had Newgate Prison. There were taverns and lumberyards and meat processing warehouses. I’ve always been struck by how the Village remained fairly isolated from the rest of the city partly because for a long time it was not connected to uptown districts by the big north-south avenues.

Seventh and Sixth Avenues sliced through the neighborhood only with the construction of the subways, which is why there are now all these crazy little triangle sites where you see the backs of old houses facing onto the avenues. We’ll get to them later. You mentioned immigrants. The Village morphed into a neighborhood for Italians in the South Village, Germans and others to the west, with clusters of African Americans in the so-called Minettas and around Cornelia Street. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there were several very different Villages.

It was still an Italian, working-class neighborhood where I grew up. We were talking about the Stonewall Inn and I led us off track. What was that building before it was a bar?

It was a pair of two-story horse stables. Then in 1930, the facade was redone, with brick on the bottom, stucco and flower-box balconies on top, which you see in old photographs. In 1934, it became Bonnie’s Stonewall Inn, a restaurant and bar, which closed in 1964. Shortly after, the gay bar that took over adopted the old name and kept the exterior signage.

A bar for both men and women?

Occasionally women, mostly younger men, some of whom were gender nonconforming. Lesbians patronized various Mafia-run lesbian bars elsewhere in the Village, like the Sea Colony and Kooky’s.

Stonewall is now a landmark but clearly not for its architecture.

Another way to say this is that buildings have lives. When we advocated for the city to designate Stonewall a landmark, I remember a guy speaking up at a public hearing, saying he was in favor of designation, but that we should not forget that Stonewall was in fact a dreary dump.

But as Lillian Faderman, a historian of lesbian history, has put it, Stonewall “sounded the rally for the movement,” leading to the founding of organizations like the Gay Liberation Front, the Gay Activists Alliance, and the Radicalesbians. The Christopher Street Liberation Day march, on the one-year anniversary of Stonewall, became the annual Pride Parade, which now happens in dozens of countries.

Just west of Stonewall, I also want to point out 59 Christopher Street, a building that housed the last headquarters of the New York City chapter of the Mattachine Society, an early national gay rights organization — at the time the phrase was “homophile organization” — founded in Los Angeles in 1950. After Stonewall, the Mattachine Society was supplanted by more radical groups, but it was important pre-Stonewall for doing many significant things, as we will see when we get to Julius’ bar, just up the street. I want to stop first at 15 Christopher, where the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop relocated in 1973.

A Federal rowhouse. I would pass it on my way to and from P.S. 41, my elementary school.

The casement windows on the second floor were probably added in the 1920s — casement windows became popular then — and those very large ground-floor picture windows came later. They made the bookstore welcoming, but vulnerable. Someone threw a brick through them at one point. The shop had been founded in 1967 by Craig Rodwell, originally in a tiny storefront on Mercer Street, near Waverly Place. Then Rodwell moved it to Christopher to make it more conspicuous and central to the gay community. The goal was to be a relaxed, friendly place where young people would feel comfortable, where everybody was welcome. Among his papers at the New York Public Library are touching letters from people who describe standing outside the bookshop for an hour trying to get up the courage to go in. It became a second home for many gay people. Alison Bechdel said that she came to the shop as a young lesbian, not sure what she wanted to do with her life, and saw all these gay and lesbian comic books, and that inspired her to become a graphic novelist.

Rodwell also hired a multiracial staff, which was a statement in itself at the time.

It lasted until 2009, when the internet was beginning to kill independent bookstores, and general-interest bookshops were selling L.G.B.T.Q. literature.

Julius’, just a few steps away, is at the corner of Waverly and 10th Street.

One of the oldest gay bars in New York.

In the mid-60s the Mattachine Society decided to challenge the New York State Liquor Authority policy that a bar could be closed down if it knowingly served a homosexual. Dick Leitsch, the Mattachine Society president; Rodwell, the bookstore owner, who was its vice president; and John Timmons, another society member, decided to go to bars along with newspaper reporters, announce they were gay, ask for a drink, and wait to be denied. They went to a Ukrainian American place on St. Marks Place that had a sign: “If you are gay, please go away.” One of the reporters apparently tipped off the bar beforehand, so it closed before the group arrived. Then they went to a Howard Johnson’s on Sixth Avenue.

I remember that Howard Johnson’s.

They sat down, asked to see the manager, said “We’re homosexuals,” and then ordered drinks. The manager just laughed and served them. So that didn’t work. They tried a Polynesian-themed bar called Waikiki and the same thing happened. Finally, they decided to go to Julius’ because Julius’ had recently been raided, and they figured the bar owners would probably be wary. They were right. There’s a photograph of the bartender refusing to serve them.

Fred McDarrah’s famous picture. In the photo you see the bartender with his hand over one of the glasses.

Heading west on Christopher toward Seventh Avenue South, there’s the wonderful 1930s “taxpayer” at the corner, which was once home to Stewart’s Cafeteria.

What’s a taxpayer?

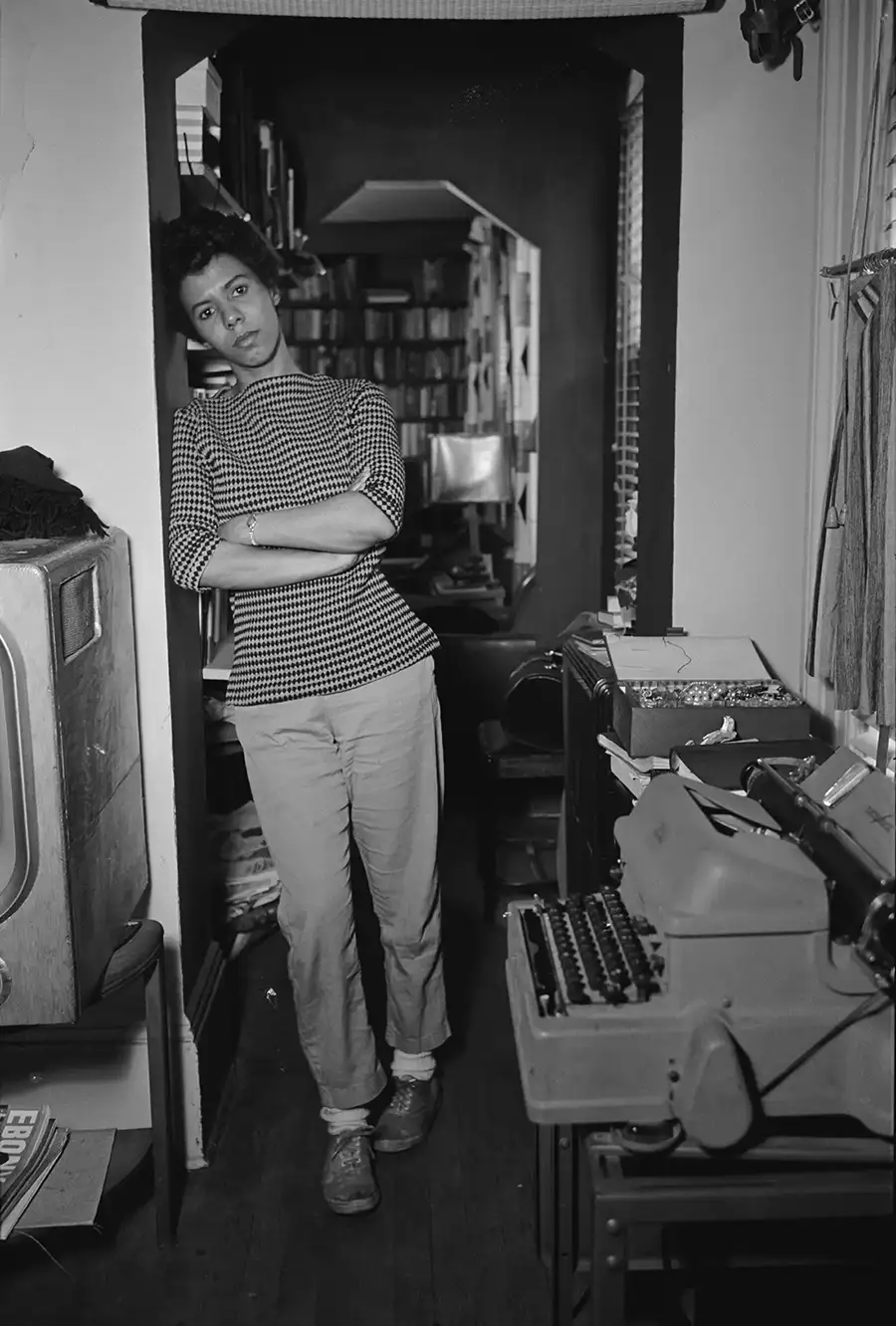

A building built to cover the site’s property taxes until the owner could afford to construct something more extravagant. There had been a plan to put up an apartment house on this corner, designed by George & Edward Blum, but with the Depression it was never built and instead we still have this wonderful two-story Art Deco building, whose first tenant was Stewart’s Cafeteria. Stewart’s was a popular chain of the era and this branch became a famous haunt for a flamboyantly gay and lesbian crowd, performing for tourists who would sometimes stand three or four people deep, staring through the windows. Further west, down Christopher Street, I wanted to point out 337 Bleecker Street, where Lorraine Hansberry wrote “A Raisin in the Sun.”

A simple, three-story Italianate-style building from the 1860s.

The building is fine, but I mention it because of Hansberry. She was a writer and also a civil rights activist. She moved into the apartment on the third floor with her husband in 1953, and when they separated in 1957, she privately comes out among a circle of lesbians, writing under a pseudonym for a journal called “The Ladder,” which was the national monthly magazine of the Daughters of Bilitis, the lesbian equivalent of the Mattachine Society. Hansberry’s social circle at the time included lesbian writers like Patricia Highsmith, who lived with her parents from 1940 to 1942 at 48 Grove Street while she was a student at Barnard. A few blocks from there, the journalist Anna Rochester and Grace Hutchins, a fellow labor reformer, lived in an apartment at 85 Bedford Street from 1924 through Anna’s death in 1966, until Grace’s death in 1969. Rochester and Hutchins had what historians now would refer to as a Boston marriage, a term that derives from Henry James’s “The Bostonians” — they were women from affluent backgrounds who lived together in very close, loving relationships. A few doors down from their building, the poet Edna St. Vincent Millay lived at 75½ Bedford, a tourist attraction today because it’s just about nine feet wide. Millay lived there during the 1920s with her husband when she was openly bisexual.

And around the corner from 75½ Bedford is the Cherry Lane Theater, in a former brewery on Commerce Street, which over the years became closely associated with gay playwrights like Edward Albee.

You said you wanted to talk about all those vestigial triangles and other remnants along Seventh Avenue South.

They were created when the avenue was cut through the neighborhood, exposing the rear facades of buildings like 70 Bedford Street, whose back became 54 Seventh Avenue South. That’s where the Women’s Coffeehouse, a lesbian-owned coffeehouse, opened in 1974. Judy O’Neil and Shari Thaler were its owners. They wanted to provide a feminist alternative to the Mafia-controlled lesbian bars. They were committed to issues around women and children, especially the rights of lesbian mothers in divorce cases involving custody. Across the street was another lesbian bar called Crazy Nanny’s, which occupied the ground floor of 21 Seventh Avenue South.

An unadorned brick building from the mid-1950s, on one of those triangular sites. The bar advertised itself as “100 percent women owned and 100 percent women managed,” and like the Oscar Wilde bookshop its staff and clientele were racially diverse.

That was significant because back then Black women didn’t feel welcome at a lot of lesbian bars (or Black men at men’s bars, for that matter). Crazy Nanny’s advertised itself as “a place for women, biological or otherwise,” meaning it welcomed trans women, at a time when that was controversial in lesbian circles. During the AIDS epidemic, lesbians also really stepped up — Crazy Nanny’s was a prime example — in ways that helped bring the gay and lesbian communities together.

Andrew, may I ask, do you have a Village story of your own?

I grew up in Midwood, Brooklyn, and I had no notion that gay communities existed in the world. I went to the Village to look at buildings and saw all these gay people on the street. I hadn’t come out yet. But this got me thinking. So I made up a story for my parents, and I went back to explore the neighborhood at night.

And that was transformative?

It was an awakening.

“Intimate City: Walking New York,” by Michael Kimmelman, will be published on Nov. 29 by Penguin Press.

Michael Kimmelman is the architecture critic. He has reported from more than 40 countries and was previously chief art critic. While based in Berlin, he created the Abroad column, covering culture and politics in Europe and the Middle East. He is the founder and editor-at-large of a new venture focused on global challenges and progress called Headway. @kimmelman

Testimony in Support of the Proposed Designation of the Julius’ Bar Building as a New York City Landmark

November 11, 2022

To be presented by Project co-director, Andrew Dolkart, at the NYC Landmarks Preservation Committee public hearing on Tuesday, November 15, 2021.

My name is Andrew Dolkart, and I am one of the co-directors of the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, a cultural heritage initiative founded by historic preservationists in 2015 to document historic places connected to the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community in the city’s five boroughs.

The Project strongly supports the designation of the Julius’ Bar Building as a New York City Landmark. In the early 1990s, my co-directors, Jay Shockley and Ken Lustbader, and I were part of the Organization of Lesbian and Gay Architects + Designers (OLGAD), a pioneering group that advocated for LGBT historic sites at a time when the field of historic preservation paid little attention to sites of cultural significance, let alone ones connected to the LGBT community. In 1994, OLGAD created what we believe is the first map in the country to document LGBT historic places, and the building that houses Julius’ was included in this effort.

In 2015, when the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project formed, one of our first priorities was to continue what OLGAD began more than twenty years earlier. We took the initiative to undertake the necessary research and write the text for the nomination of Julius’ to the National Register of Historic Places, which was approved in April 2016, one day before the 50th anniversary of the so-called “Sip In”.

Julius’ is located just a few minutes’ walk from the more famous Stonewall Inn, but its place in LGBT history is just as significant. The events at Stonewall in June 1969 did not exist in a vacuum. In the decades leading up to that uprising, bars were one of the few places that LGBT people could gather openly. Yet, at the same time, there were always inherent risks since the mere presence of a homosexual in a bar was considered to be disorderly: frequent police raids and other forms of entrapment could lead to arrest, loss of employment, and physical and mental abuse, among other threats. With photographers in tow, the game-changing public action by the Mattachine Society on April 21, 1966, which culminated at Julius’, was the earliest planned effort to capture LGBT discrimination in real time.

When we give walking tours in the area, we typically end at Julius’, and young people, in particular, are often surprised to learn that at one time, even in New York City, even in Greenwich Village, LGBT people faced these hardships in bars, of all places. Julius’ is therefore not only a great place to gather and have drinks with friends, but also a valuable teaching tool.

We thank Helen Buford, the owner of Julius’, for her incredible stewardship of the bar and its history, and for collaborating with and supporting our Project from the very beginning. The NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project proudly supports this proposed designation.

Thank you.

Landmarks Holds Public Hearing for Lesbian Herstory Archives

November 9, 2022

By: Cassidy Strong

On October 25, 2022, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing to discuss landmarking the Lesbian Herstory Archives in Park Slope, Brooklyn. Located at 484 14th Street within the Park Slope Historic District, the building was previously calendared for Individual Landmark consideration on June 28.

The public hearing began with a presentation from Landmarks’ Deputy Director of Research Margaret Herman, who described the Lesbian Herstory Archives as “the nation’s oldest and largest collection of lesbian-related historical material.” The 14th Street building was constructed in the Renaissance Revival style by architect Axel Hedman in 1908, and the volunteer-led Lesbian Herstory Archives have been housed there since 1991. Herman shared that the Archives paid off their mortgage in 1996, creating a permanent headquarters, and has “diligently maintained” the building ever since.

However, the Lesbian Herstory Archives moved into their current space after the creation of the Park Slope Historic District, leaving no mention of their work. Designating the building as an individual landmark, Herman explained, would emphasize the building’s LGBTQ+ significance.

Following Herman’s presentation, Landmarks turned the hearing over to public testimony. Saskia Scheff, one of the coordinators at the Lesbian Herstory Archives and a volunteer there since 1989, began by testifying in support of the landmarking. Scheff stated that the Archives are a landmark not just because of the building, but for their work as a community organization and interactive catalog of history.

Scheff was followed by Amanda Davis, Project Manager of the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project. Davis stated that the project “strongly supports the designation of the Lesbian Herstory Archives as a New York City Landmark,” pointing out that it would be the first LGBT site to be landmarked in Brooklyn. Davis also shared that when the project first launched its website with an initial 100 sites, the Lesbian Herstory Archives was included, and that the Archives’ resources have been “invaluable” to the project’s work. Since the Archives were created out of a lack of lesbian visibility, and Park Slope as a neighborhood is home to a large lesbian community, Davis affirmed that the project “proudly supports the proposed designation.”

Colette Montoya, who has worked with the Archives since 2011 and is currently working to digitize their collection 3000 audio cassettes, similarly emphasized the building’s importance to the greater NYC lesbian community. Montoya, an indigenous woman, also highlighted the Archives’ commitment to recording the history of the Lenape people, who originally inhabited what is now NYC.

Next, Lucie Levine spoke on behalf of the Historic Districts Council, who also “enthusiastically supports” the building’s designation as an Individual Landmark. Levine stated that cultural landmarks like the Lesbian Herstory Archives are a growing priority for the HDC, and called upon Landmarks to recognize more cultural landmarks with ties to marginalized communities. Levine was followed by Katherine Prater and Elizabeth Daly, members of the public who also spoke in support of the landmarking.

Sonia Guior, Landmarks Director of Community and Intergovernmental Affairs, ended the public testimony period by noting that 25 letters were also sent in support, 2 of which were written by community organizations.

With no additional questions from Commissioners, Chair Sarah Carroll closed the public hearing and shared her own excitement about the proposed designation. Carroll thanked the the Lesbian Herstory Archives for being “great supporters” of Landmarks, as well as the LGBT Historic Sites Project, “who has also been a great partner with us as we have started to, and have continued to work through, our priorities and thinking about equity in our designations”.

Landmarks will continue their research, incorporating testimony from the public hearing, and will hold a vote on designating the Lesbian Herstory Archives “in the very near future.”

By: Cassidy Strong (Cassidy is a CityLaw intern and a New York Law School student, Class of 2024.)

LPC: Lesbian Herstory Archives, LP-2662. October 25, 2022

Plaque Unveiling at Caffe Cino, on Joe Cino’s 91st Birthday

November 17, 2022

The following remarks were presented by Amanda Davis, NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project manager, at the November 16, 2022 unveiling of the plaque at the former Caffe Cino, celebrating the building on the National Register of Historic Places.

Thank you to everyone who has come out today to celebrate the Caffe Cino, which Joe Cino opened nearly 65 years ago here at 31 Cornelia Street. I’d like to thank David Wilder and the staff of Bombay Bistro for collaborating with us today on this plaque unveiling and to the Cino alums that are here today, especially Magie Dominic, who will be sharing some remarks after me. We would not have been able to list the Caffe Cino on the National Register of Historic Places without Magie’s archive and knowledge of the Caffe Cino.

My name is Amanda Davis, and I’m the project manager of the New York City LGBT Historic Sites Project. We’re a cultural heritage initiative that, since 2015, documents historic places in the city’s five boroughs that have important connections to the LGBT community, from the 17th century to the year 2000. Our website features an interactive map of over 400 places (and counting), and we also give walking tours, host public programs, and advocate for official landmark status to help formalize the significance of LGBT historic sites in New York and American history.

In 2017, we successfully listed the Caffe Cino building to the National Register of Historic Places, in recognition of its significance as the birthplace of Off-Off-Broadway and as a pioneer in the development of gay theater at a time when depicting homosexuality on stage was illegal. The Caffe Cino is one of my favorite sites that I’ve ever researched – a wonderfully quirky, vibrant, and touching story that comes right out of the pages of what Greenwich Village must have been like during the 1960s. For most of the 20th century, this area was very Italian, something that Joe Cino would use to his advantage when he stood here, in December 1958, with his then-boyfriend, Ed, who showed Joe a “for rent” sign on the storefront space at 31 Cornelia Street and introduced him to the landlady, Mrs. Leema, who was looking out her upstairs window. Once they made the connection that she was Italian and Joe was Sicilian, Mrs. Leema said, “I don’t even have to come down, I’ll throw the keys.” And from there, Joe said, in his only known interview, he and Ed “went in and viewed the ruins.” He saw the potential in the tiny room, already envisioning where the counter and coffee machine would go.

The Caffe Cino opened soon after and by 1960, plays were being staged. A year later, playwright Doric Wilson helped establish the Cino as a venue for new work with four plays – two of which included gay themes. The Cino’s breakthrough hit came in 1964 with the staging of Lanford Wilson’s The Madness of Lady Bright, which was centered on an aging drag queen slowly going mad alone in his room. It was so popular that within a year, the Caffe became particularly well known for presenting gay or gay-friendly works. The most successful production here was Dames at Sea, which introduced teenager Bernadette Peters in 1966.

It’s impossible to tell the Cino’s whole story today or even mention the impressive list of theater artists associated with it, but perhaps it’s best summed up by saying that the Cino was a place where Joe Cino encouraged anyone to write about anything they wanted. For gay playwrights, in an era of widespread homophobia, this provided a level of freedom to write gay-themed work at a level never before experience on the New York stage. The Caffe Cino is, as I like to say, a true testament to the arts as a powerful platform for change. In the 1960s, before the Stonewall Uprising and the Gay Liberation era led to increased visibility for LGBT people, gay theater artists at the Cino gave audiences rare public exposure to multi-dimensional and realistic gay characters, and, in doing so, challenged the negative and stereotypical portrayals that had permeated

mainstream theater and film for decades. What we see on stage or on screen very often affects how we view each other and even view ourselves. Although the Cino closed in 1968, following the tragic suicide of Joe Cino a year earlier, the gay theater that it had nurtured continued to evolve with the emergence of gay theater companies, some of which were founded by Cino alums.

We’re honored to be able to unveil the National Register plaque on what would be Joe Cino’s 91 st birthday, and also celebrate the return of the plaque donated by playwright Robert Patrick in 2008.

Pictured, Amanda Davis with Tevin Williams, representing State Sen. Brad Hoylman.

NYC’s Oldest Gay Bar May Soon Get Landmark Status

November 16, 2022

By: Sharon Crowley

NEW YORK – Regulars at Julius Bar in Greenwich Village are eager for the city of New York to designate the tavern as a local historical landmark.

“It’s really important to have the city recognize Julius as a city landmark,” said Ken Lustbader, the co-director of the New York City LGBT Historic Sites Project.

The Stonewall Inn was cemented as the birthplace of the gay rights movement in the U.S. because of the infamous uprising there in 1969. But what many people don’t know is that in 1966 a group of gay men staged an earlier protest trying to get served at the counter.

“At that time it was illegal to serve known homosexuals alcohol and if they did so they could lose their license, so this was the first public action to show discrimination in real time,” Lustbader said.

New York State Senator Brad Hoylman, who is gay, says the project is personal.

“There were brave men who stood up to the NYPD and the mob and bar owners and made certain our rights were protected by law and that’s what happened at Julius, and we should never forget that,” Hoylman said.

Julius Bar is already listed on the National Register of Historic Places and supporters are hoping to get local status so that New York City also recognizes its place in history.

NYC’s Oldest Gay Bar May Soon Get Landmark Status

November 16, 2022

By: Rana Novini

A bar since 1864, Julius’ was thrust into the forefront of the gay rights movement in 1966 — three years before the Stonewall riots — when activists staged a peaceful “sip in,” announcing they are homosexuals and asking to be served

Before the Stonewall Inn became known as the birthplace of the gay rights movement in the U.S., and the riots that helped bring the movement into the national spotlight, there was Julius’.

Located in the heart of Greenwich Village, at West 10th Street and Waverly Place, manager Adan Garcia said that being in the bar is like being inside a living museum. The storied history that has taken place there is on full display in photos on the walls.

Now there is an effort to preserve that history, with an official New York City Landmark designation that is one step closer to reality for the legendary establishment.

“It’s a landmark to me. I’m sure it’s a landmark to many many people who walk through those doors,” said Garcia.

Julius’ has been a bar since 1864. It was thrust into the forefront of the gay rights movement in 1966 — three years before the Stonewall riots.

Photos show three members of the Mattachine society, a gay rights organization, challenging a regulation that prohibited bars from serving LGBTQ people. The activists staged a peaceful “sip in,” announcing they are homosexuals and asking to be served.

In a photograph that gained widespread media attention, a bartender at Julius’ held his hand over their glasses and refused to serve them.

“Still to me it just boggles my mind,” Garcia said.

Andrew Dolkart, with the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, is one of the people fighting for Julius’ Bar to get a city landmark designation. He said it would formalize the bar’s significance in New York and American history.

“These young men who took part in this event, this was incredibly courageous,” said Dolkart. “We need to know where we’ve been, where we are and where we need to go.”

The city’s Landmarks and Preservation Committee held a public hearing Monday where many spoke about why the Greenwich Village mainstay should be recognized. For now, the bar waits, but Adan is already planning the celebration.

“I’ll make sure we’ll decorate everything perfectly,” he said.

There was no opposition to the proposal at the hearing. For the next step, the commission will schedule a public hearing for a vote.

Plaque Unveiling for Caffe Cino

November 16, 2022 | 2:30 PM

Bombay Bistro (former home of the Caffe Cino)

31 Cornelia Street

View on Google Maps

The Caffe Cino operated from 1958 to 1968 and was owned by Joe Cino, an openly gay man. The cafe theater venue is recognized as the birthplace of Off-Off-Broadway and was a pioneer in the development of gay theater, at a time when depicting homosexuality on stage was still illegal. In 2017, the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project successfully nominated the Caffe Cino space to the National Register of Historic Places for its significance to LGBT history.

We invite you to celebrate the Caffe Cino with us as we unveil a plaque at 31 Cornelia Street in Greenwich Village, its former home, on what would have been Joe Cino’s 91st birthday. The plaque recognizes the Cino’s listing on the National Register. We’ll be joined by Bombay Bistro, the current tenant of the space, Magie Dominic, a Cino alum whose archives were invaluable in writing the National Register nomination, as well as a number of special guests.

You can read more about the Caffe Cino on our project page. We hope to see you there!

Audre Lorde’s New York

November 8, 2022

By: Amanda Davis

Last month, I participated in “A Celebration of Audre Lorde,” a virtual event that was hosted by the College of Staten Island. The evening was full of wonderful remembrances and discussions of Lorde and her work. This year marks a couple of anniversaries related to the self described “Black, lesbian, feminist, mother, poet warrior”: she moved to Staten Island 50 years ago with her family and, after a hard fought battle with breast cancer, she died 30 years ago this November 17th. (October was chosen for the event to coincide with Breast Cancer Awareness Month; it’s also LGBT History Month).

My portion of the evening focused on historic places on our website that connect to Lorde’s legacy. Here’s a little snapshot of Audre Lorde’s New York:

Audre Lorde bought this house at 207 St. Paul’s Avenue in Stapleton Heights in 1972 and lived here with her partner Frances Clayton and two children. The family unfortunately dealt with racism while living here but Lorde also noted that the home’s garden, trees, and proximity to the water were some of the reasons she chose to move to Staten Island. A photo taken by Joan E. Biren (JEB) shows Lorde writing away at her desk in her upstairs study. This is where she wrote some of her most famous work, including (but not limited to) Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982). She and her family lived here until 1987. Read more about Lorde’s connection with this house.

One of our Project’s goals is to expand the number of designated LGBT landmarks in New York City. In a meeting with the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC), the city agency that designates and regulates the city’s landmarks, we advocated that this house, along with several others, become a New York City Landmark. After a public hearing in June 2019 — where we, of course, testified in support! — LPC commissioners voted to designate the house and five other sites, making Lorde’s home the first LGBT-related New York City Landmark outside Manhattan.

In Zami, Lorde wrote of several lesbian bars in Greenwich Village that she frequented in the 1950s, providing an invaluable account of nightlife in this period for lesbians in general and Black lesbians in particular. Of the Pony Stable Inn at 150 West 4th Street, she noted that “There were always rumors of plainclothes women circulating among us, looking for gay girls with fewer than three pieces of female attire. That was enough to get you arrested for transvestism, which was illegal.”

Bars historically were safe spaces for the LGBT community, but there were also risks involved. We’ve created a curated theme on Bar Raids and Forced Closures that puts this into context.

Several lesbian women we’ve spoken to fondly recall The Bagatelle at 86 University Place. Lorde referred to it in Zami as “the most popular gay-girl’s bar in the Village” but, at the same time, many Black lesbians did not feel welcome there. She recalled, “the bouncer was always asking me for my ID to prove that I was twenty-one…Of course ‘you can never tell with Colored people.'”

This is what made groups like the Salsa Soul Sisters so important to lesbians of color, providing an alternative to bars where they had historically faced discrimination. Black lesbian luminaries like Audre Lorde were invited to speak on various topics, creating a space that was rare for lesbians of color in 1970s America, according to member Candice Boyce.

The group grew out of the Black Lesbian Caucus of the Gay Activists Alliance, which met at the GAA Firehouse in SoHo in the early 1970s. Salsa Soul’s first regular meeting space was the Metropolitan-Duane United Methodist Church (now Church of the Village) but its longtime home was in the parish house of Washington Square Park United Methodist Church.

Let’s end with an archival photograph (always my favorite!) of Womanbooks, which was located at 201 West 92nd Street on the Upper West Side from 1975 to 1987. The bookstore doubled as a community center for women regardless of sexuality, race, or political affiliation, and was another one of several places in the city where Audre Lorde spoke to lesbian audiences.

What are some of the other places where she made her mark in the city? Type her name in the search bar at the top of the website or watch the recording of “A Celebration of Audre Lorde” below. Participants include faculty and students of the College of Staten Island, Debbie-Ann Paige of the Staten Island African American Heritage Tour, and Victoria Munro of the Alice Austen House who spoke with Lorde’s sister comrades.

NYC LGBTQ historic sites project receives ‘excellence’ award

November 6, 2022

By: Lou Chibbaro Jr.

The National Trust for Historic Development has chosen the New York City LGBT Historic Sites Project as the recipient of its Trustees Award for Organization Excellence.

The LGBT Historic Sites Project is one of nine historic preservation-related organizations that were recognized with awards at a Nov. 4 virtual ceremony that was available to the public.

“The NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project is a nationally recognized and influential cultural heritage initiative and educational resource that identifies and documents diverse extant LGBT sites from the 17th century to 2000,” the announcement says.

“The only permanent organization of its kind in the U.S., the project staff have created an interactive website, National Register nominations, publicans and programs and school educational materials, among other resources,” the announcement continues.

‘Sitting at the intersection of historic preservation and social justice, the organization has been particularly eager to document LGBT sites associated with women and Black, Asian, Latinx, trans and gender-variant communities,” according to the announcement. “In the near future, they hope to prioritize local sites of LGBT history associated with Indigenous and Two-Spirit peoples,” it says.

In its announcement, the National Trust for Historic Preservation says its National Preservation Awards ceremony is held each year during its annual PastForward Conference, which was held virtually on Nov. 4.

“Each year at the PastForward Conference we come together to recognize those making a real difference in historic preservation,” said Paul Edmondson, president and CEO of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. “This year’s recipients embody not just the preservation of American History, but also demonstrate how preserving historic places can play a key role in addressing critical issues of today, including climate change, equality and housing,” Edmondson said.

NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project To Receive Prestigious Trustees’ Award From the National Trust for Historic Preservation

November 4, 2022

By: A.A. Cristi

The NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project’s work to identify and document NYC’s place-based LGBT history is being honored by the National Trust for Historic Preservation today, Friday, November 4th, at 4PM EST with their Trustees’ Award for Organizational Excellence, one of our field’s highest honors. The award will be given at the PastForward Conference, in a ceremony hosted by old house icon Bob Vila.

“Our Project makes visible historic narratives that have been actively erased or willfully ignored by the larger culture for generations. By reconnecting LGBT history to physical, extant sites, we create a visceral connection that instills pride and fosters a sense of belonging to a larger community. We know this work inspires other marginalized groups whose history is part of the full American story,” said Ken Lustbader, co-director of the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project.

“This national award helps amplify the importance of documenting LGBT historic places and including these stories in the broader telling of American history. One of our Project’s most rewarding elements is connecting LGBT people around the world to their own history, much of which has long been hidden and intentionally erased. We hope this award encourages people to embrace LGBT history in their communities.” – Amanda Davis, manager of the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project

“This national award helps amplify the importance of documenting LGBT historic places and including these stories in the broader telling of American history. One of our Project’s most rewarding elements is connecting LGBT people around the world to their own history, much of which has long been hidden and intentionally erased. We hope this award encourages people to embrace LGBT history in their communities.” – Amanda Davis, manager of the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project

“Each year at the PastForward Conference we come together to recognize those making a real difference in historic preservation. This year’s recipients embody not just the preservation of American history, but also demonstrate how preserving historic places can play a key role in addressing critical issues of today, including climate change, equality, and housing.” – Paul Edmondson, president and CEO of the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Since its founding in 2015, the Project has now identified, researched and mapped over 400 sites across New York City’s five boroughs which connect the public viscerally to the places – residences, bars and venues, public spaces, and more – where LGBT people have contributed to American culture.

About the Trust’s selection of the Project for the 2022 Trustees’ Award for Organizational Excellence: The NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project is a nationally-recognized and influential cultural heritage initiative and educational resource that identifies and documents diverse extant LGBT sites from the 17th century to 2000. The only permanent organization of its kind in the US, the project staff have created an interactive website, National Register nominations, publications and public programs, and school educational materials, among other resources. Sitting at the intersection of historic preservation and social justice, the organization has been particularly eager to document LGBT sites associated with women and Black, Asian, Latinx, trans, and gender-variant communities. In the near future, they hope to prioritize local sites of LGBT history associated with Indigenous and Two Spirit Peoples.

The NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, launched in 2015 by preservation professionals, is an award-winning cultural heritage initiative and educational resource documenting and presenting historic sites connected to the LGBT community throughout New York City. Its website, including an interactive map, features over 375 diverse places from the 17th century to 2000 that are important to LGBT history and illustrate the community’s influence on NYC and American culture.

The project researches and nominates LGBT sites to the National Register, advocates for the official recognition of LGBT historic sites, provides walking tours (also accessible through a free-app), presents lectures, engages the community through events, develops educational programs for New York City public school students, and disseminates its content through robust social media channels. Its goal is to make an invisible history visible while fostering pride and awareness.

NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project honored with award for ‘making a once invisible history visible’

November 5, 2022

By: Muri Assunção

A New York City nonprofit that focuses on documenting sites that are connected to the city’s rich LGBTQ history and culture has been recognized for its “trailblazing approach to making a once invisible story visible.”

The NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project on Friday received the Trustees’ Award for Organizational Excellence from the National Trust for Historic Preservation, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit that works in the field of historic preservation in the United States.

The award, which honors “superlative and continued achievement in historic preservation by an organization,” was presented to Ken Lustbader, the organization’s co-founder and co-director.

“Having the Washington-based, National Trust for Historic Preservation, recognize LGBTQ site-based history is important and helps legitimize our work,” Lustbader told the Daily News.

“The imprimatur of the Trust sends the message that LGBTQ history is part of the American experience and story,” he added. “It will help pave the way for other projects around the country.”

Their work is “especially important now with the pushback on LGBT rights throughout the country,” Lustbader said when accepting the honor.

State Senator Brad Hoylman, a Manhattan Democrat and a powerful voice for LGBTQ rights, told The News that the group’s recognition “shows that queer history is American history,” calling the honor a “triumphant moment for our communities.”

For the past seven years, the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project has been an authoritative voice in the preservation of historic sites that have been closely associated with the LGBTQ community across the five boroughs.

Its website includes a robust searchable and interactive map that features nearly 400 sites — including cultural institutions, queer- and trans-owned residences, businesses and bars — that paint a clear picture of the LGBTQ influence on American culture.

Launched in 2015 by Lustbader, Andrew Dolkart and Jay Shockley — three renowned experts in LGBTQ history, documentation, and historic preservation— the initiative has documented historic and cultural sites that helped to form the narrative of the LGBTQ liberation movement in New York City, from the 17th century until the year 2000, with a goal of documenting an important part of history that could be otherwise forgotten or overlooked.

At that time, there were only two sites listed in the National Register for Historic Places for their LGBTQ associations. Today, there are 27 across the U.S., 11 of which are in New York City.