Washington Square Park

overview

Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village became known as a gay meeting place and cruising area from the late 19th century through the 1960s.

Following the Stonewall uprising of 1969, it became a space associated with LGBT activism.

On the Map

VIEW The Full MapHistory

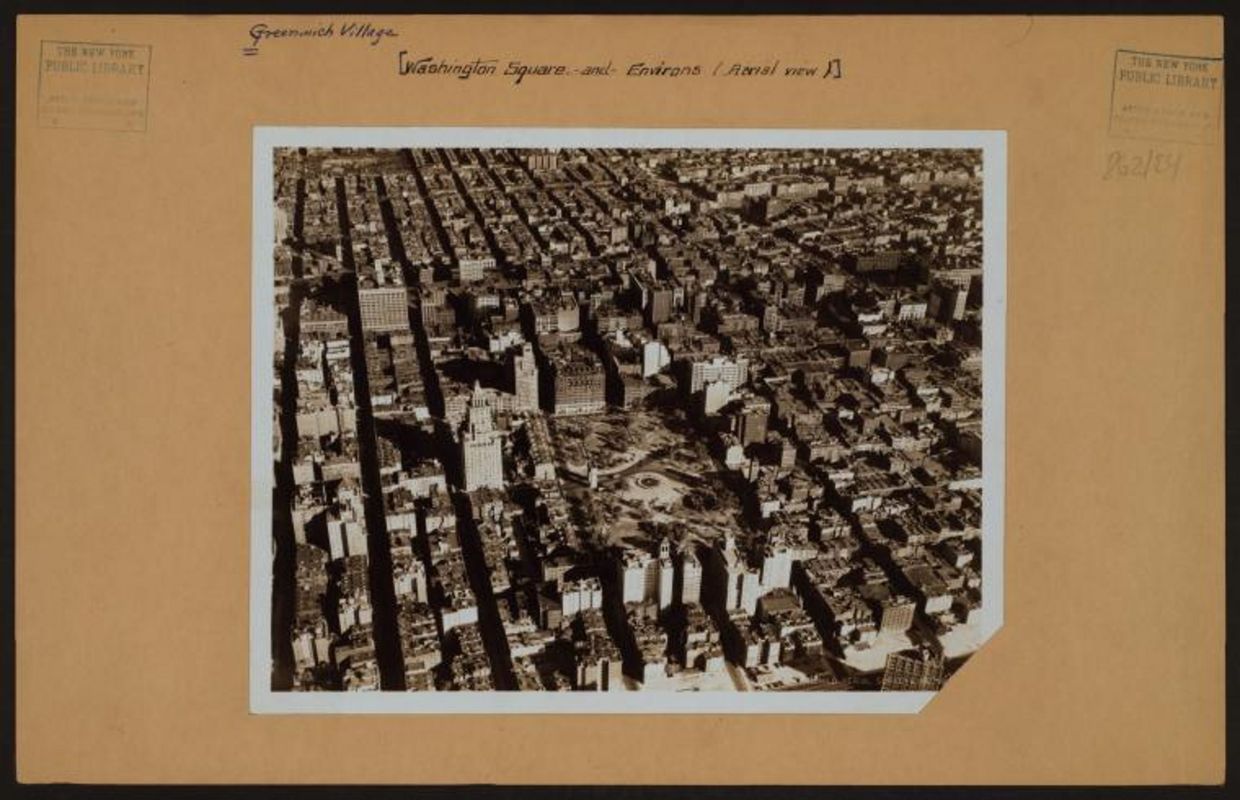

Washington Square Park began as a Potter’s Field and public execution place in 1797 and was used as a Military Parade Ground in 1826. It was then established as a public park in 1827. As the major park for Greenwich Village, it became an important gathering space for various groups, including LGBT people, artists, bohemians, and New York University students. Sites with LGBT significance that face the park include the Eleanor Roosevelt Residence, the Larry Kramer Residence, the Edie Windsor & Dr. Thea Clara Spyer Residence, Judson Memorial Church, and the Sam Wagstaff Residence.

According to historian George Chauncey, parks were the most popular and secure gay meeting places in New York City, and by the late 19th century, Washington Square Park was an established cruising area where gay men could find “privacy in public” by meeting friends and finding sexual partners. The west side of the park, along the fence, was the major cruising area and was referred to as “the Meat Rack.” The park was so well known as a gay area that a song from the late 1910s proclaimed that “Fairyland’s not far from Washington Square.” Gay men were arrested for cruising in the park beginning in the 1910s, and by the 1920s, visible male sex workers could be seen in the park.

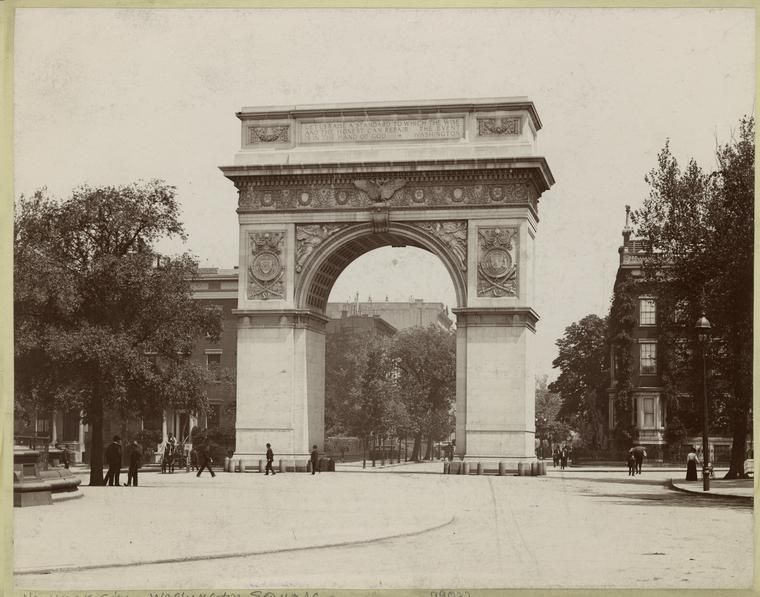

By the mid-20th century, Washington Square Park was regarded as a historic open space and was home to many monuments, such as the Washington Arch. In the early 1950s, the Washington Square Park Committee was founded to oppose a plan by then Parks Commissioner Robert Moses to construct a four-lane roadway through the middle of the park. At a 1958 public hearing, former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who from 1942 to 1949 lived in an apartment building located at 29 Washington Square Park West, testified in support of the committee’s proposal to forever close Washington Square Park to all motor vehicles.

Washington Square Park was officially closed to traffic in August 1959, and the committee’s plan to preserve the park as a venue for cultural and recreational activities inadvertently set the stage for its emergence as a place of LGBT activism in the late 1960s.

“The Meat Rack” was still a known cruising locations in the 1960s, and according to playwright and actor David Leddick, “in Greenwich Village the gay men were lined up every night along the western side of Washington Square. They sat and lounged against the low pipe railings there, which were called ‘the Meat Rack.’” Gay hustlers also populated Washington Square during the 1960s, and Andy Warhol reportedly stocked his early Factory with men from the square whom he met at the nearby San Remo Café. The Washington Square Park was also identified as a cruising area in New York Unexpurgated, a 1966 guide to “underground Manhattan.” Historian John D’Emilio further documents that in February 1966, Mayor John Lindsay instituted a massive crackdown on “honky tonks, promenading perverts… homosexuals, and prostitutes” that began in Times Square and extended to Washington Square Park and resulted in a sharp rise in arrests.

A month after the Stonewall uprising, on July 27, 1969, a contingent of the newly-formed Gay Liberation Front marched from Washington Square Park to Christopher Park (often mislabeled as Sheridan Square) carrying lavender-colored banners with interlocking male and female symbols and chanting “Gay power!… Gay power to the gay people!” Martha Shelley and Marty Robinson of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) spoke to the revolutionaries assembled in Washington Square Park. Shelley galvanized the crowd and denounced the prejudice and harassment endured by gay people, stating, “The time has come for us to walk in the sunshine. We don’t have to ask permission to do it. Here we are!… We’re tired of being harassed and persecuted. If a straight couple can hold hands in Washington Square, why can’t we?”

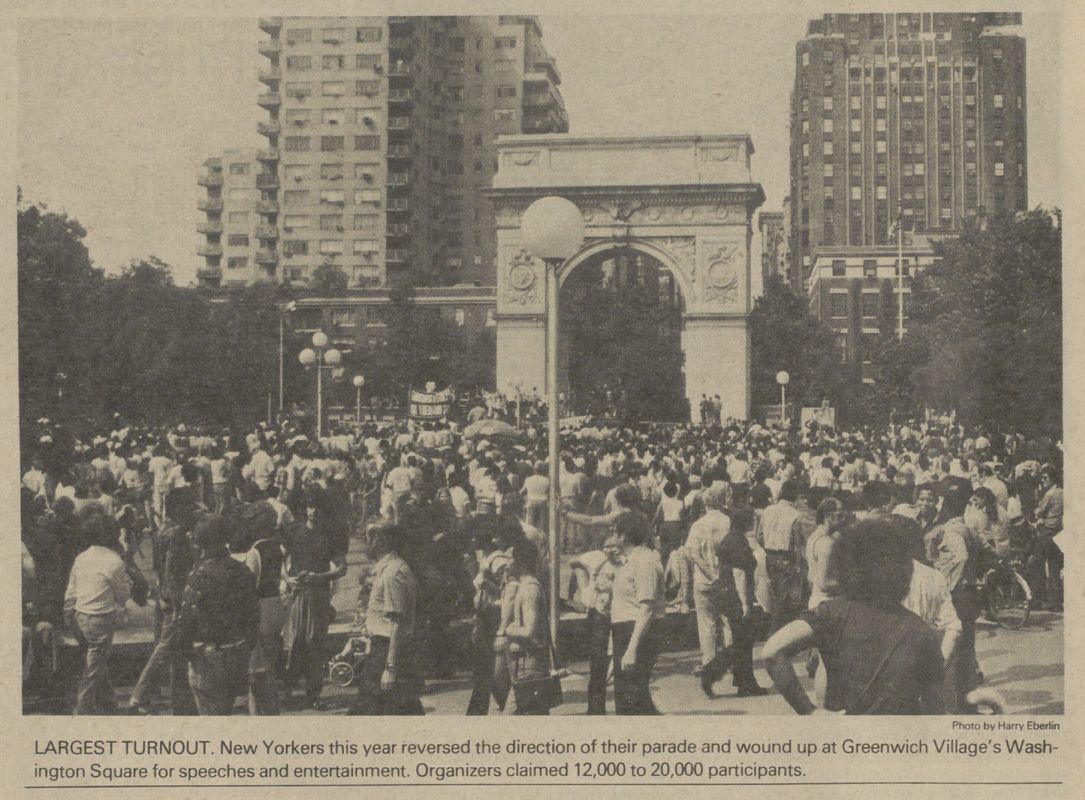

The fourth annual Christopher Street Liberation Day March (today’s Pride March), held on June 24, 1973, began in Central Park and ended, for the first time in the march’s then-brief history, in Washington Square Park. The march culminated in three-and-a-half hours of speeches and entertainment in the park, held on a professional stage that had been installed in front of the Washington Arch. Veteran lesbian activist Barbara Gittings delivered a keynote address in which she listed the accomplishments of the gay liberation movement and led the crowd in a chant of “Gay is good! Gay is proud! Gay is natural! Gay is normal! Gay is gorgeous! Gay is positive! Gay is healthy! Gay is happy! Gay is love!”

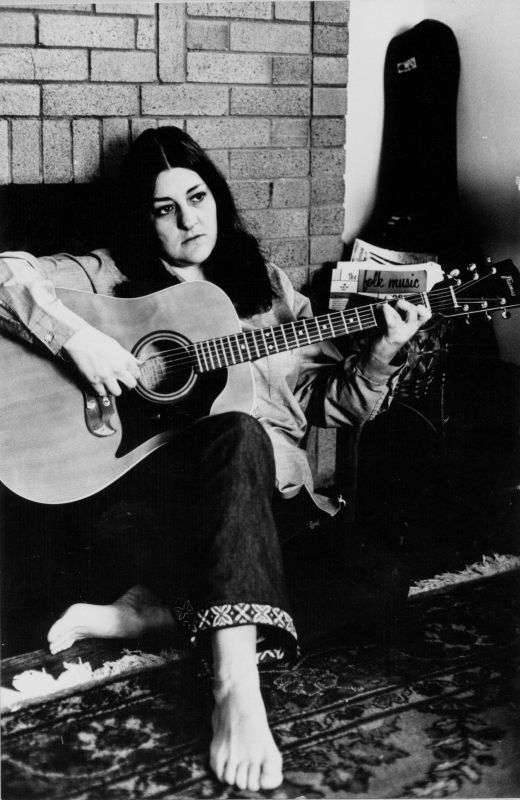

Master of ceremonies Vito Russo then introduced Los Angeles gay rights leader Morris Kight, calling him “the dean of the Gay Liberation movement.” The entertainment was opened by Madeline Davis, a lesbian activist and folk singer from Buffalo, New York, who sang her anthem “Stonewall Nation,” the first gay liberation 45 rpm record. Another 22 acts followed, interspersed with the reading of telegrams from supporters, such as New York Congresswoman Bella Abzug and mayoral candidate Herman Badillo.

Jean O’Leary, of Lesbian Feminist Liberation, attempted to block Sylvia Rivera, of the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR), from taking the stage at this event. Rivera eventually broke through and delivered a fiery speech in which she indicted the gay liberation movement for its exclusion of drag queens (persons who today may identify as transgender and queer) and their concerns. Trans activist Lee G. Brewster subsequently mounted the stage and echoed Rivera’s sentiments before throwing a Queens Liberation Front banner into the crowd. Following this disturbance, Russo ushered actress and singer Bette Midler onstage in an attempt to calm the agitated crowd.

The event, which had a 7:00 p.m. curfew, ran long, and the police shut the power off at 7:20. The final three performers continued without amplification. Organizers claimed 12,000 to 20,000 participants attended the 1973 march and festival.

Since 1996, the annual New York City Dyke March, first organized in 1993 by the Lesbian Avengers, has commenced at Bryant Park and ended in Washington Square Park. The Trans Day of Action, an annual rally and march organized by the Audre Lorde Project’s Trans Justice Group, has taken place in the park since 2005. Washington Square Park remains a home to protests, celebrations, and rallies for LGBT rights to this day.

Entry by Jeffry Iovannone, project consultant (March 2023).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Ignatz Pilat, assisted by Montgomery Kellogg

- Year Built: 1827; 1870, 1964, and 2009-14 renovations

Sources

Blanche Wiesen Cook, Eleanor Roosevelt, Volume 3: The War Years and After, 1939-1962 (New York: Viking, 2016).

David Carter, Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2004).

David Leddick, “Being Gay in the World of Mad, Mad Men: What it Was Really Like,” Huffington Post, May 17, 2012, accessed March 19, 2023, bit.ly/3FAl3nt.

Emily Kahn, “NYC Dyke March,” NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, June 2020, accessed January 29, 2022, bit.ly/3DotCAx.

Emily Kies Folpe, “A Short History of Washington Square Park,” Washington Square Park Conservancy, 2002, accessed January 28, 2022, bit.ly/3Y4eYXh.

George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 (New York: Basic Books, 1994).

“A History of Pride Around the Park,” Washington Square Park Conservancy, June 8, 2017, accessed January 29, 2022, bit.ly/3WNZbuL.

Jay Shockley, “Gay Liberation Front at Alternate U.,” NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, March 2017; revised January 2023, accessed January 28, 2022, bit.ly/3HdH3oh.

John Darnton, “Homosexuals March Down 7th Avenue,” The New York Times, June 25, 1973.

John D’Emilio, Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities, 2nd edition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998).

Ken Lustbader, “Eleanor Roosevelt Residence,” NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, March 2017, accessed January 28, 2022, bit.ly/3HF7lB6.

Lige Clarke and Jack Nichols, “New York Notes,” Los Angeles Advocate, October 1969.

“New York Adds Park Festival,” The Advocate, February 13, 1974.

Randy Wicker, “Gays Pour Through New York,” The Advocate, July 18, 1973.

“Shirley Hayes and the Preservation of Washington Square Park,” NYC Parks, accessed January 28, 2022, bit.ly/40aTqdm.

“Washington Square: New York Haven for Bohemians and Activists,” National Park Service, accessed January 28, 2022, bit.ly/3wAzqmW.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?