Robert Mapplethorpe Residence & Studio

overview

Robert Mapplethorpe was one of the most influential and controversial photographers of the 20th century, known as much for his unflinching depictions of gay sado-masochistic sex as the outrage they induced.

This building was the location of Mapplethorpe’s first and primary studio, which he kept from 1972 until his death in 1989, and where he created some of his most iconic images.

On the Map

VIEW The Full MapHistory

Robert Mapplethorpe (1946–1989) moved to the fifth floor loft at 24 Bond Street, in what was still an industrial area in lower Manhattan, in October 1972. The young artist bought the space, converting much of it to a studio and darkroom, with money given to him by Sam Wagstaff, the influential art curator and collector. Wagstaff, Mapplethorpe’s patron, mentor, and long-term lover, would later buy Mapplethorpe an apartment at 35 West 23rd Street, allowing Mapplethorpe to keep 24 Bond Street as a workspace until his death due to AIDS-related complications in 1989.

Of his hometown, Floral Park, Long Island, Mapplethorpe once quipped, “it was a good place to come from in that it was a good place to leave.” Moving to Brooklyn in the early 1960s, Mapplethorpe studied drawing, painting and sculpture at Pratt Institute where he met his soul-mate and muse, the punk poet and musician Patti Smith. By the end of the decade he and Smith moved to the Chelsea Hotel, where they occupied its smallest room. At this point in his artistic career, Mapplethorpe was using images he found in gay porn magazines to create collages with various materials. Mapplethorpe’s focus on photography began in the mid-1970s, when he found the use of his own images in his artworks to be more authentic. Due in large part to Wagstaff’s financial and intellectual support, and the space and facilities he now had at 24 Bond Street, his photography career took off.

The Bond Street loft never changed. In the front was sort of no man’s land and that was where he used to photograph a lot. Then you move back and there’s this little seating area, where he would always hold court. Across from that was the bedroom painted black gloss with the handcuff holds above the bed.

By his staff’s accounts—and those of the men he sometimes enticed back to his studio for sex, drugs and photography sessions—24 Bond Street was, at different times, a den of eye-watering vice and a bustling workspace. Edward Mapplethorpe (his brother and studio assistant beginning in 1982) said, “Anybody who was involved in that studio will agree with me that you just got sucked into Robert’s world. You wanted to, I mean you just did. It was an interesting world, it was a lot of excitement, a lot of fun.” Tom Baril, Mapplethorpe’s printer from 1979 to 1989, described Mapplethorpe’s studio process: “there would always be film in the morning from the night before, so the first thing I’d do was process film. He’d come in in his robe, ‘how were the films Tom?’”

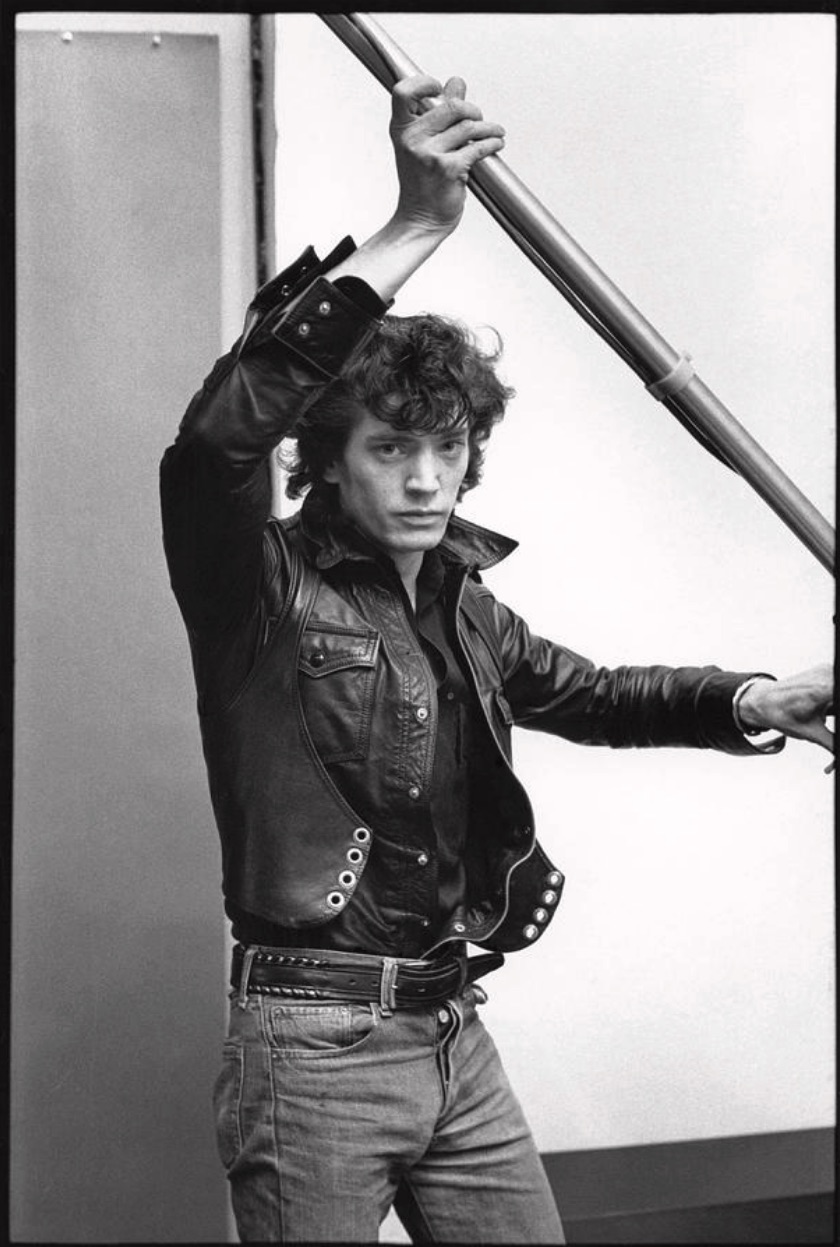

Mapplethorpe’s photographs are a snapshot of the city’s 1980s cultural scene. Legions of celebrities, artists, writers, musicians, and even European aristocracy were photographed at the Bond Street studio, such as Patti Smith, Grace Jones, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Isabella Rossellini, Keith Haring, Louise Bourgeois and Andy Warhol. Alongside this lucrative work, Mapplethorpe took still lifes of flowers and statuary, and portraits of his sexual partners, many of whom he found at New York’s premier sex club, The Mineshaft. Bond Street was also the site of one of Mapplethorpe’s most famous images, Man in Polyester Suit (1980), a photograph of his lover and model Milton Moore—an example of his obsession with the Black male form.

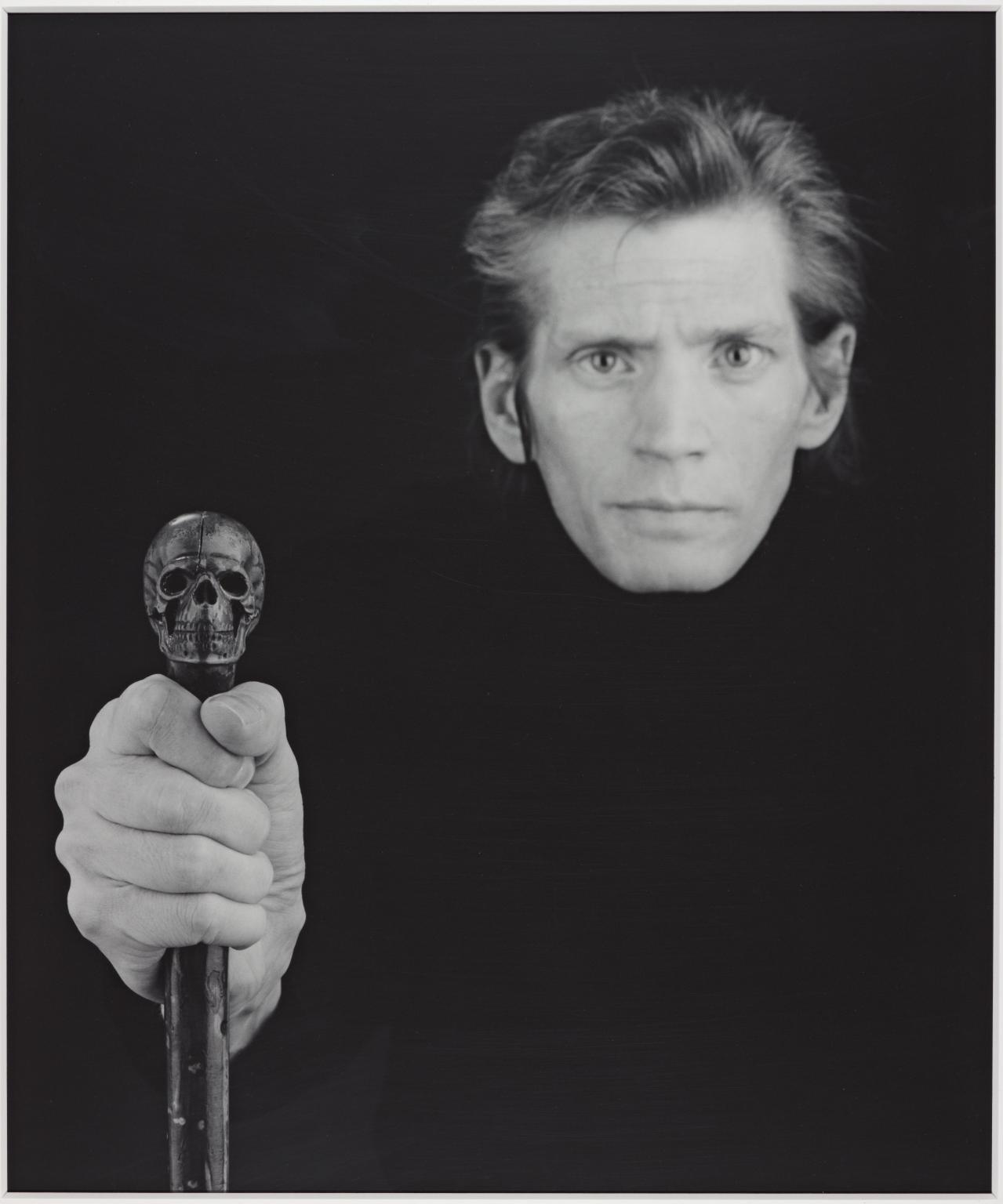

Mapplethorpe’s final self-portrait—taken at 24 Bond Street in 1988 as his health was deteriorating—was, according to biographer Patricia Morrisroe, “one of his finest photographs, and certainly his most intimate.” The iconic image shows him gripping a cane topped by a carved image of a skull, his own face receding into the darkness of the background. Taken around the same time as his major and highly controversial retrospective at the Whitney Museum, the image—photographed with precision, tight focus, and a richness of blacks, whites and greys—exhibits the results of his excessive lifestyle, while retaining a sense of his unbridled ambition and endless self-publicity, even in the face of death. His final self-portrait perfectly encapsulates Mapplethorpe’s 17-year career at 24 Bond Street.

After his death, Mapplethorpe’s photographs continued to be collected by some of the world’s most prestigious art museums, but also continued to cause controversy. An exhibition of his work at the Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center in 1990 led to it becoming the first museum in America ever to be taken to court on criminal charges related to works on display. The museum won its case defending the artistic merit of Mapplethorpe’s work and caused a seismic shift in the estimation of photography as art. Though controversial, Mapplethorpe’s images did more to elevate photography’s place in the art world than almost any other American photographer of the 20th century. The waves caused by his activity at Bond Street can still be seen emanating through the worlds of art, fashion and museum curation today.

Entry by George Benson, project consultant (July 2020).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Buchman & Deisler

- Year Built: 1893

Sources

Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures, Dirs. Fenton Bailey, Randy Barbato, HBO Documentary Films, 2016. [source of pull quote]

“Biography,” The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, bit.ly/2WnIZnM.

Bob Colacello, “When Robert Mapplethorpe Took New York,” Vanity Fair, March 8, 2016, bit.ly/3dQJlcL.

Chelsea Dowell, “The Glittering and Gritty History of 24 Bond,” blog, Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, August 3, 2017, bit.ly/3fHDisp.

Catalina Dib, “Robert Mapplethorpe’s pictures of Grace Jones painted by Keith Haring, commissioned by Andy Warhol,” Katari Mag, n.d., bit.ly/2LjvyPA.

Brian English, “Robert Mapplethorpe, My Greatest Boss,” The Getty Iris: Behind the Scenes at the Getty, March 16, 2016, bit.ly/3cpIMpW.

Miss Rosen, “Inside the Final Years of Robert Mapplethorpe’s Studio,” Huck Magazine, March 28, 2019, bit.ly/3ctFtxP.

Patricia Morrisroe, Mapplethorpe: A Biography (Boston: Da Capo Press, 1997).

“The Photographs of Robert Mapplethorpe,” Tate, bit.ly/2AhLUWt.

“Robert Mapplethorpe, Smutty,” Tate, bit.ly/2zxgIlX.

“Robert Mapplethorpe,” Wikipedia, bit.ly/2LkdPra (accessed May 12, 2020).

Jonathan Van Meter, “How Artist Edward Mapplethorpe Got His Name Back,” New York Magazine, September 14, 2007, nym.ag/2AfBOFA.

“Robert Mapplethorpe, Self-Portrait, 1988,” The Whitney Museum of American Art, bit.ly/2WqVgrG.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?