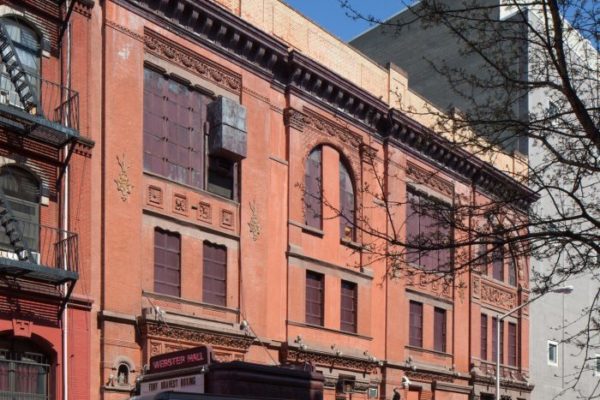

Peter Hujar Residence & Studio / David Wojnarowicz Residence & Studio

overview

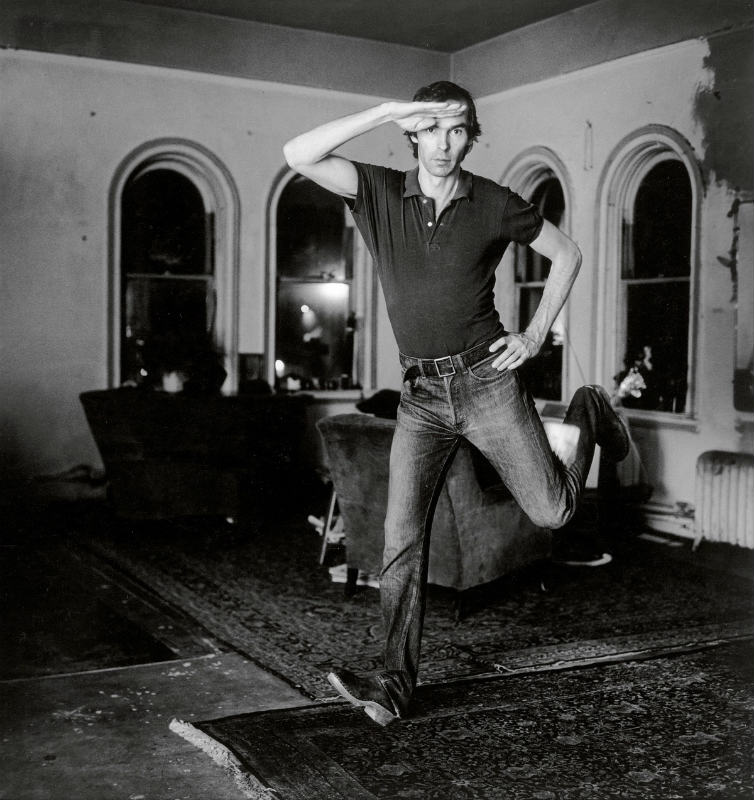

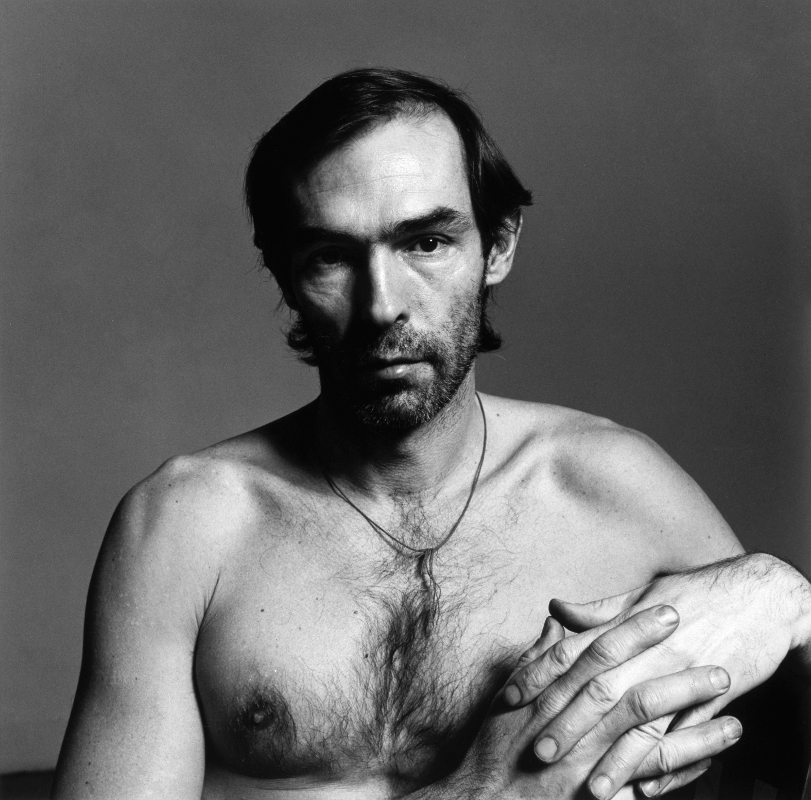

Photographer Peter Hujar was barely recognized in his lifetime but, since his death due to AIDS-related pneumonia in 1987, he has come to be regarded as one of the greatest American photographers in the 20th century. Hujar lived and worked in a loft on the second floor of the historic theater at 189 Second Avenue from 1973 until his death in 1987. He took over the apartment from “Warhol Superstar” Jackie Curtis.

A fearless political firebrand, the radical artist David Wojnarowicz challenged the art world and lambasted America for failing the LGBT community, particularly in response to the AIDS crisis. Wojnarowicz lived and worked in Hujar’s former loft from 1988 until his death from AIDS in 1992.

See Louis N. Jaffe Art Theater for more information about this site’s LGBT history.

On the Map

VIEW The Full MapHistory

In the 1960s, the offices on the second floor of the Louis N. Jaffe Art Theater, at the corner of East 12th Street and Second Avenue in the East Village, began to be converted into apartments. At least three notable LGBT people in the performing arts and visual arts fields have lived here.

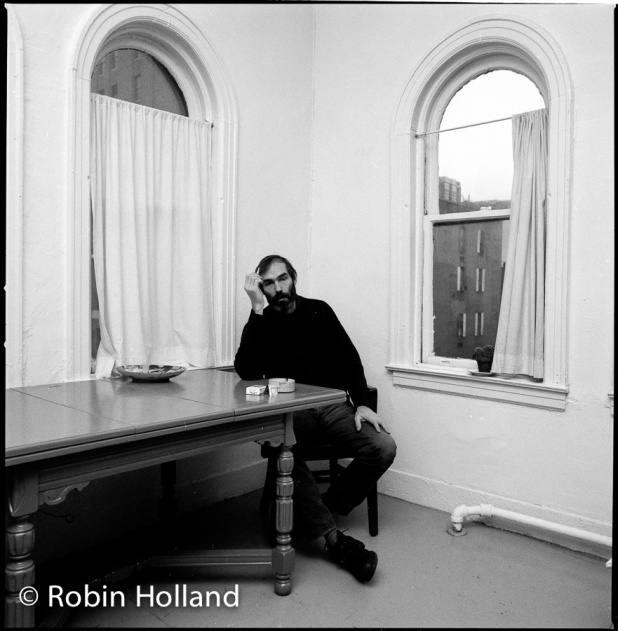

Peter Hujar Residence & Studio

Jackie Curtis (1947-1985), prolific playwright, director, performer, poet, and Warhol Superstar, resided in a loft on the second floor from 1968 or 1969 to 1973. When Curtis moved to an apartment at 324 East 14th Street, Peter Hujar (1934-1987), a friend from New York’s underground film, poetry, theater, and music scenes, then occupied the space. Curtis would also frequent the loft during Hujar’s occupancy.

The definition of an impoverished artist, Hujar lived here in relative anonymity for the rest of his life. A stalwart of the Lower East Side art scene, Hujar was a towering figure in the community, often donning the role of tutor or parental figure to up-and-coming artists, such as Nan Goldin, Gary Schneider, Kiki Smith, and, in particular, David Wojnarowicz, who saw Hujar as “like the parent I never had, like the brother I never had.”

Born in Trenton, New Jersey, in 1934, Hujar grew up on a farm with his Ukrainian grandparents. His father abandoned the family before he was born and his mother left him in New Jersey to work in New York City, occasionally returning to begrudgingly give money towards Hujar’s upbringing. After graduating from the School of Industrial Art (later the High School of Art and Design), and at the urging of Daisy Aldan—a poet, editor, and English teacher who recognized his artistic talent—Hujar got apprenticeships in commercial photography studios. Here he became a master printer and learned the skills that would later set his photography apart, eventually having a darkroom in his loft at 189 Second Avenue to develop his own work.

On a Fulbright-sponsored trip to Italy in 1963, with his then-lover, the artist Paul Thek, he took images destined to appear in his only book of photography. Published in 1976 with an introduction by his friend Susan Sontag, Portraits in Life and Death features portraits of legendary figures (some of whom were Hujar’s close friends) taken in 1974 and 1975, such as Sontag, director John Waters, actor and drag performer Divine, writer William S. Burroughs, poet Edwin Denby, editor Diana Vreeland, and writer Fran Lebowitz. He juxtaposed these portraits with corpses entombed in the catacombs of Palermo, Sicily. The book received a tepid reception, only gaining its place as a classic of American photography after Hujar’s death. Hujar continued making portraits up until his AIDS diagnosis, but also became known for capturing street scenes of the decaying New York of the 1970s and 1980s, and the uninhibited queer life that blossomed at the piers on Manhattan’s west side. Wojnarowicz joined Hujar in creating art at the piers and organized an artists’ invasion of Pier 34 at Canal Street in 1983.

Steve Turtell, poet and friend of Hujar, vividly remembers Hujar’s lifestyle at his loft at 189 Second Avenue: “I watched Peter wring out a pair of blue jeans he had just washed in his own sink and hang them over the curtain rod to dry,” so poor he couldn’t afford the laundromat. He often went without heat and emptied his household garbage into public trash cans.

[Hujar’s loft at 189 Second Avenue] was like a monk’s cell. He had what he needed and nothing more.

Despite his self-sabotaged career (Lebowitz noted at his funeral “Peter Hujar has hung up on every important photography dealer in the Western world”), Hujar had a glittering social circle and his loft was known for having a constantly open door. Those he grew closest to, and often photographed in his loft, were those he considered true artists, such as his friend, the drag performer Ethyl Eichelberger.

Hujar is now partly remembered for his intense relationship with Wojnarowicz, whom he met in 1980 and who was an unparalleled source of support, inspiration, and tutelage for the young artist. The writer Stephen Koch, to whom Hujar left his estate, said “one of the keys to [Hujar’s] personality, I later figured out, was that anyone who had been an abused child was automatically on Peter’s A list.” This was certainly the case with Wojnarowicz, and the two found solidarity in upbringings of shared hardship.

Hujar suspected he would only gain notoriety after his death, which indeed turned out to be true. He has been the subject of many exhibitions in recent years with his work lauded for revealing the inner-character of his sitters—as opposed to his contemporary Robert Mapplethorpe’s stylized celebrity portraits. Hujar died, age 53, from AIDS-related complications in 1987 at Cabrini Medical Center in New York and his funeral was held at St. Joseph’s R.C. Church.

David Wojnarowicz Residence & Studio

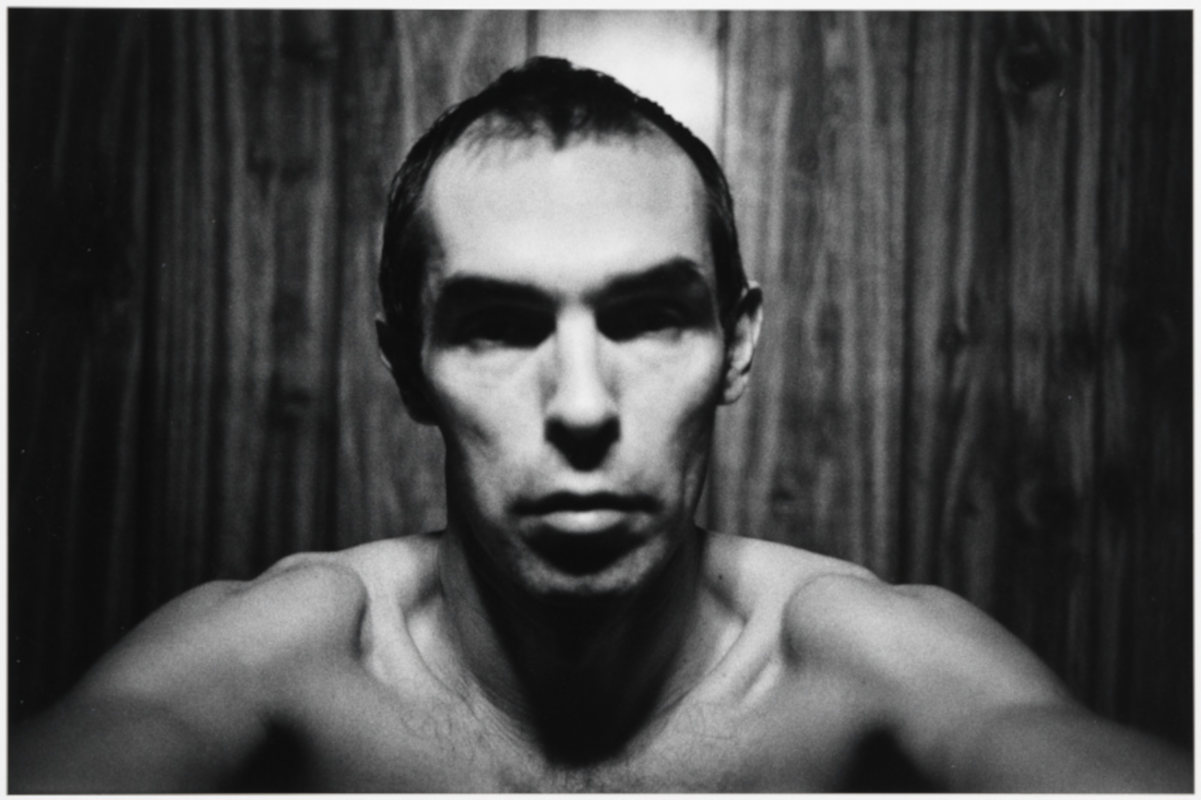

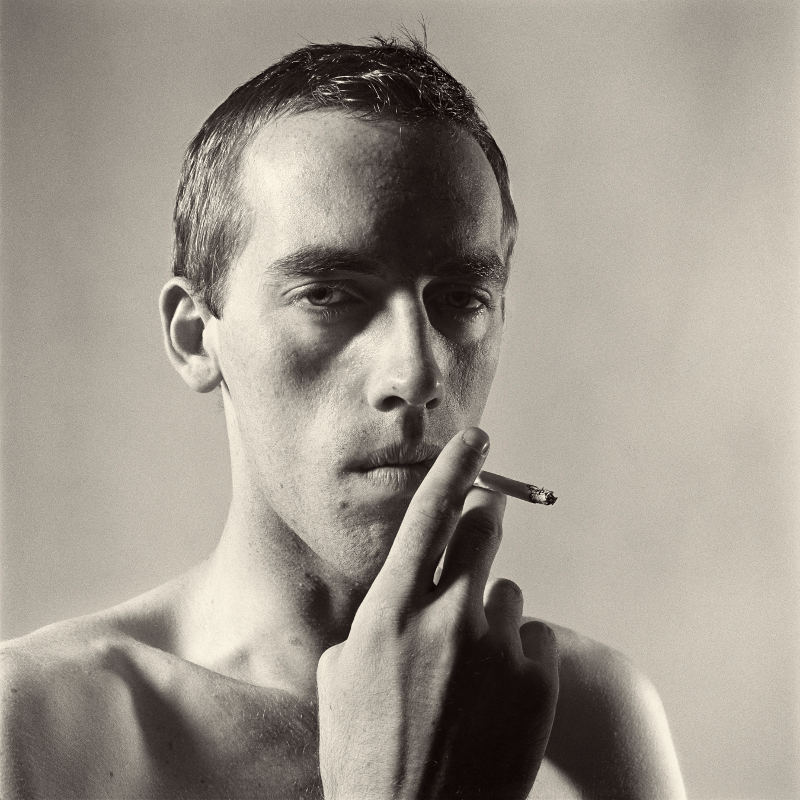

Artist David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992) lived a life of extreme hardship, but one he was able to channel into radical art, writing, and music. Writer Fran Lebowitz described Wojnarowicz’s upbringing as “a classic background for a serial killer.” He was born in Red Bank, New Jersey, in 1954 to a physically abusive father and neglectful mother. By the time he was 15 he had left home and was hustling in Times Square. He graduated from the prestigious High School for Music and Art and gravitated to the East Village where he found rapport with the characters he met there. Wojnarowicz was attracted to those he considered outside of the “pre-invented world,” his term for societal structures that influence us from birth, such as the law, language, and religion. He became one of the figureheads of the East Village art scene and inspired many into action in the fight against AIDS—he was diagnosed with the virus himself in 1988.

Wojnarowicz’s breakthrough moment came in 1985 when The Whitney Museum of American Art exhibited some of his work. His art eschews a signature visual style but always contains within it his acid wit, burning rage, and transgressive politics—reflecting his part in the culture wars that blighted America in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Perhaps his most famous artwork was created in 1990 and 1991, entitled One Day This Kid. A black and white image of himself around the age of 9, Wojnarowicz surrounds his young self with text written in his characteristically relentless rhythm. The text takes aim at societal structures that make “existence intolerable for this kid” because of their oppressive attitudes towards his sexuality.

Wojnarowicz met photographer Peter Hujar in 1980, and for both men this would be their most important relationship. After a brief romance, the two settled into a platonic spiritual bond, with Hujar acting as the father figure Wojnarowicz never had. Hujar told Wojnarowicz never to compromise in his art, advice he took to heart for the rest of his life. When Hujar died in 1987, Wojnarowicz was devastated. Overcome with sadness, he held a celebration of Hujar’s life at Hujar’s loft at 189 Second Avenue, complete with a shrine to his mentor.

Coming back to his place the candle and shrine had burnt down to a beige hard puddle. I told him out loud how sad I am… I can’t imagine my life without this man…

In January 1988, Wojnarowicz moved into the loft so that he, according to his biographer, could “breathe the same air Hujar had breathed. He would hang on to any vestige.” He utilized Hujar’s dark room, producing some of his most memorable images. Wojnarowicz was one of the first people living with AIDS to receive home care, due in part (according to his doctor) to the force of his personality. Wojnarowicz died, age 37, in the Second Avenue loft on July 22, 1992, surrounded by family and friends. One week after his death, Wojnarowicz was given the first political funeral to come out of the AIDS epidemic, organized by two members of an ACT UP affinity group. Written upon a huge banner that led the funeral procession beginning at the loft were the words: DAVID WOJNAROWICZ, 1954–1992, DIED OF AIDS DUE TO GOVERNMENT NEGLECT.

See Louis N. Jaffe Art Theater for more information about this site’s LGBT history.

Landmark Designations for LGBT Significance

In 1993, the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) designated the Louis N. Jaffe Art Theater a New York City Landmark and Interior Landmark. While the site was not designated specifically for LGBT significance, it was the second in the history of the LPC (established in 1965) to include an LGBT mention in the accompanying designation report. It was the first report to include the word “gay” in reference to three prominent residents. The report’s author, Jay Shockley, who was then in the Research Department at the LPC, went on to co-found the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project in 2015. See the report in the “Read More” section below.

Entry by George Benson, project consultant (January 2021).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Harrison G. Wiseman

- Year Built: 1925-26

Sources

C. Carr, Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2012). [source of both pull quotes]

Guy Trebay, “Peter Hujar and the Lost New York,” The New York Times, March 4, 2016, nyti.ms/3hXzbbF.

Peter Schjeldahl, “The Bohemian Rhapsody of Peter Hujar,” The New Yorker, January 29, 2018, bit.ly/3cl8AUZ.

Holland Cotter, “He Made Them Glow: A Maverick’s Portraits Live On,” The New York Times, February 8, 2018, nyti.ms/2ZXIhPq.

Simon Bowcock, “Peter Hujar: the photographer who defined downtown New York,” The Guardian, October 14, 2016, bit.ly/2ROmzJx.

Edmund White, “Why Can’t We Stop Talking About New York in the Late 1970s?,” The New York Times Style Magazine, September 10, 2015, nyti.ms/3mNXMUb.

“Press Release,” Matthew Marks Gallery, bit.ly/2GOlrmY.

“About,” The Peter Hujar Archive, bit.ly/3hTklmw.

“Peter Hujar,” Wikipedia (accessed September 22, 2020), bit.ly/302cAEG.

“Artist Biography,” Artist Archives Initiative, bit.ly/37XbnDf.

Christine Smallwood, “The Rage and Tenderness of David Wojnarowicz’s Art,” The New York Times Magazine, September 7, 2018, nyti.ms/2JrCmxh.

Moira Donegan, “David Wojnarowicz’s Still-Burning Rage,” The New Yorker, August 18, 2018, bit.ly/3aNtQnx.

“David Wojnarowicz,” Visual AIDS, bit.ly/2X4FqCN.

“David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night,” The Whitney Museum of American Art, bit.ly/3o99clL.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?