Greenwich Village Waterfront

overview

For over a century, the Greenwich Village waterfront along the Hudson River, including the Christopher Street Pier at West 10th and West Streets, has been a destination for the LGBT community that has evolved from a place for cruising and sex for gay men to an important safe haven for a marginalized queer community – mostly queer homeless youth of color.

Between 1971 and 1983 the interiors of the piers’ ruin-like terminals featured a diverse range of artistic work, including site-based installations, photography, murals, and performances.

On the Map

VIEW The Full MapHistory

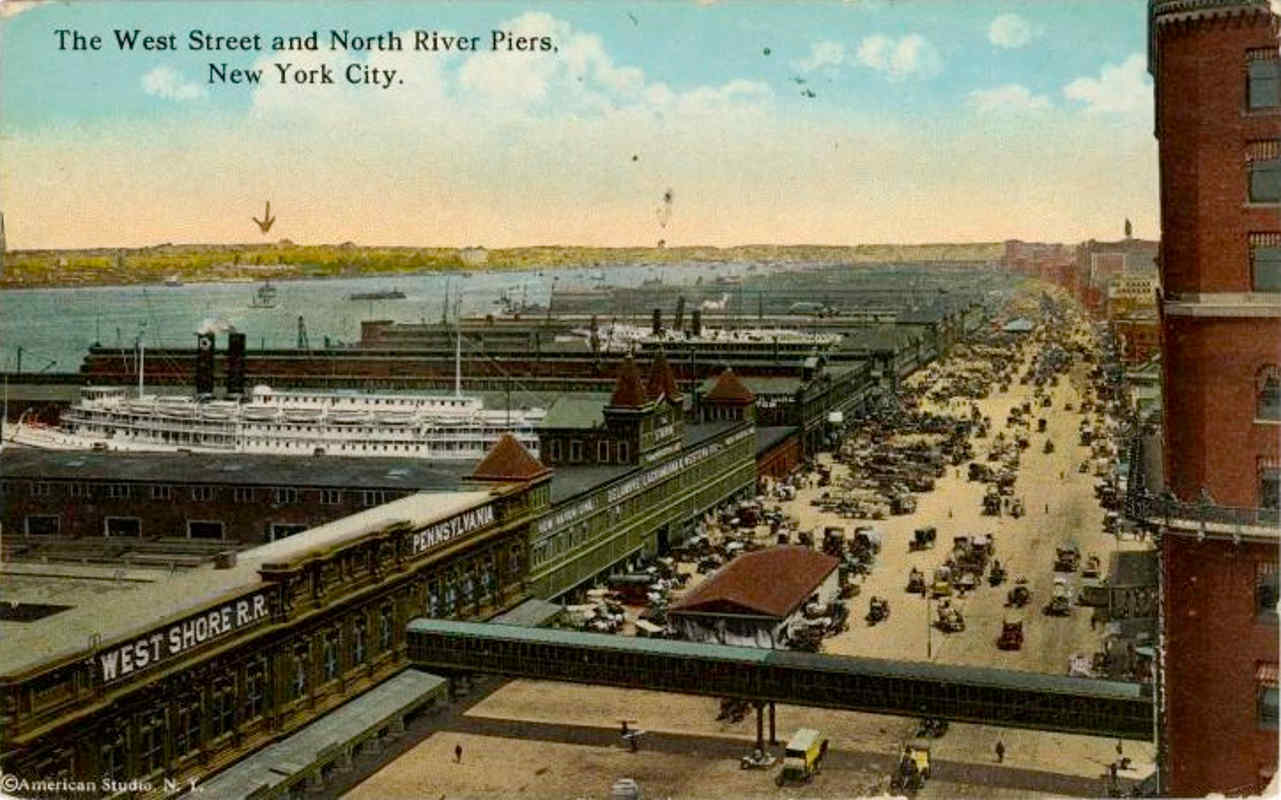

By the early 20th century, Greenwich Village’s Hudson River waterfront and numerous piers with Beaux Arts style shipping terminals comprised the busiest section of New York’s port for cargo and trans-Atlantic passengers, with merchant ships, steamships, barges, and commuter ferries. The area was surrounded by thousands of seamen of all nationalities and more than half a million unmarried and transient workers came into the port each year.

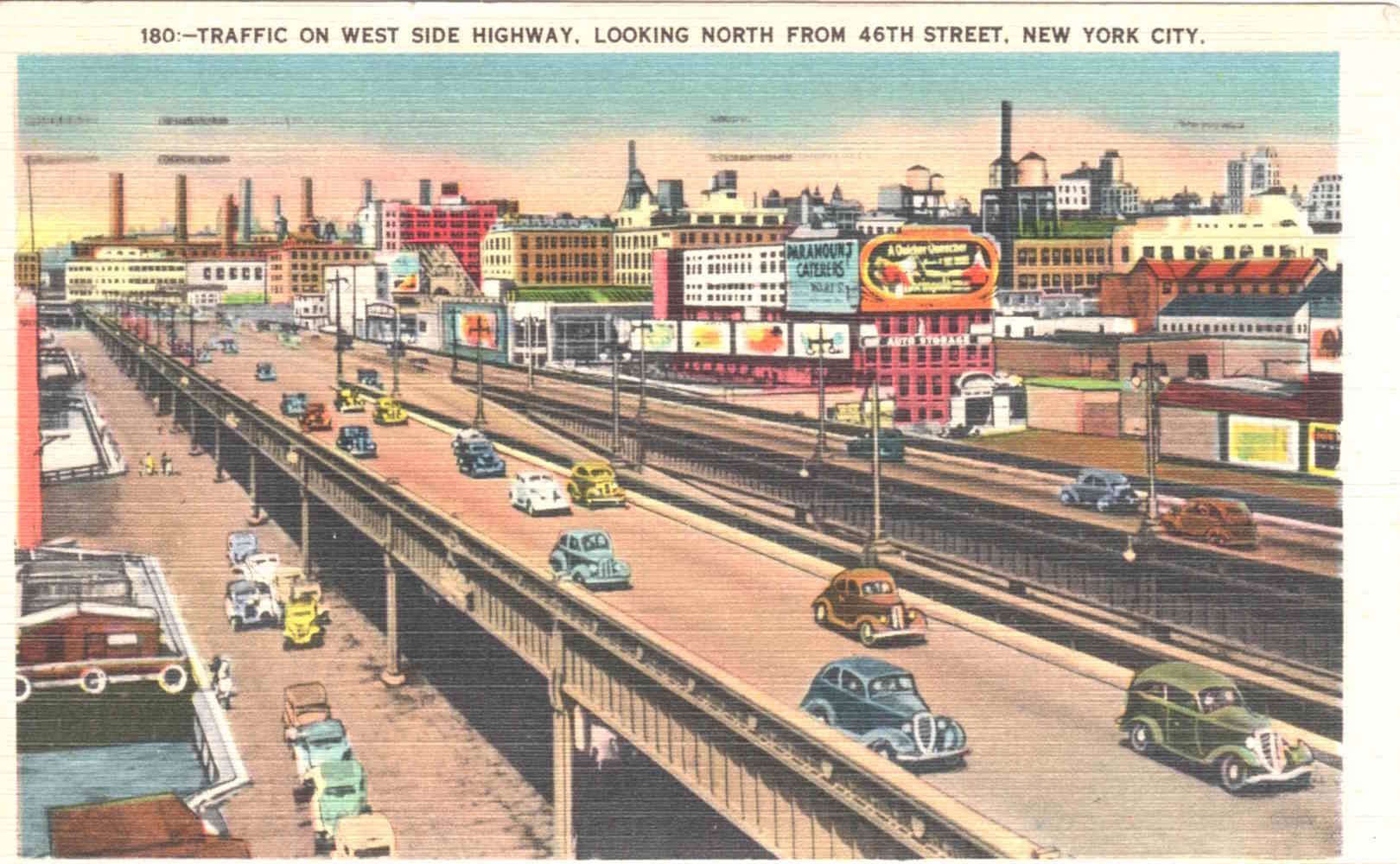

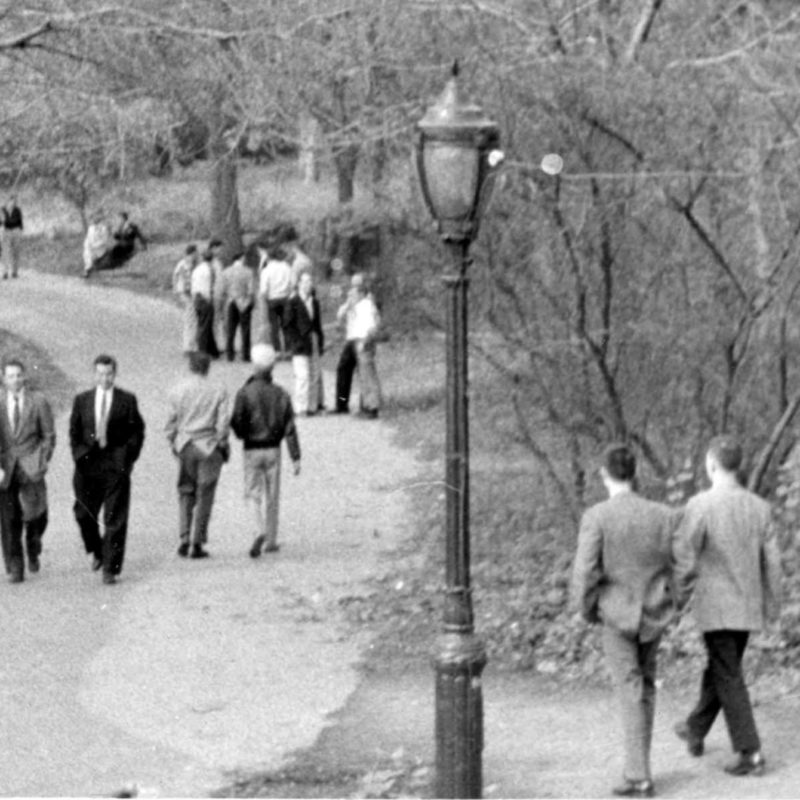

At least by World War I, the area had become a popular cruising area for gay men, and by the 1930s the opening of the elevated Miller (West Side) Highway (now demolished) cut through the area. The concentration of men, numerous bars and warehouses, and nighttime isolation established the waterfront as one of the main centers for gay life that thrived well after World War II.

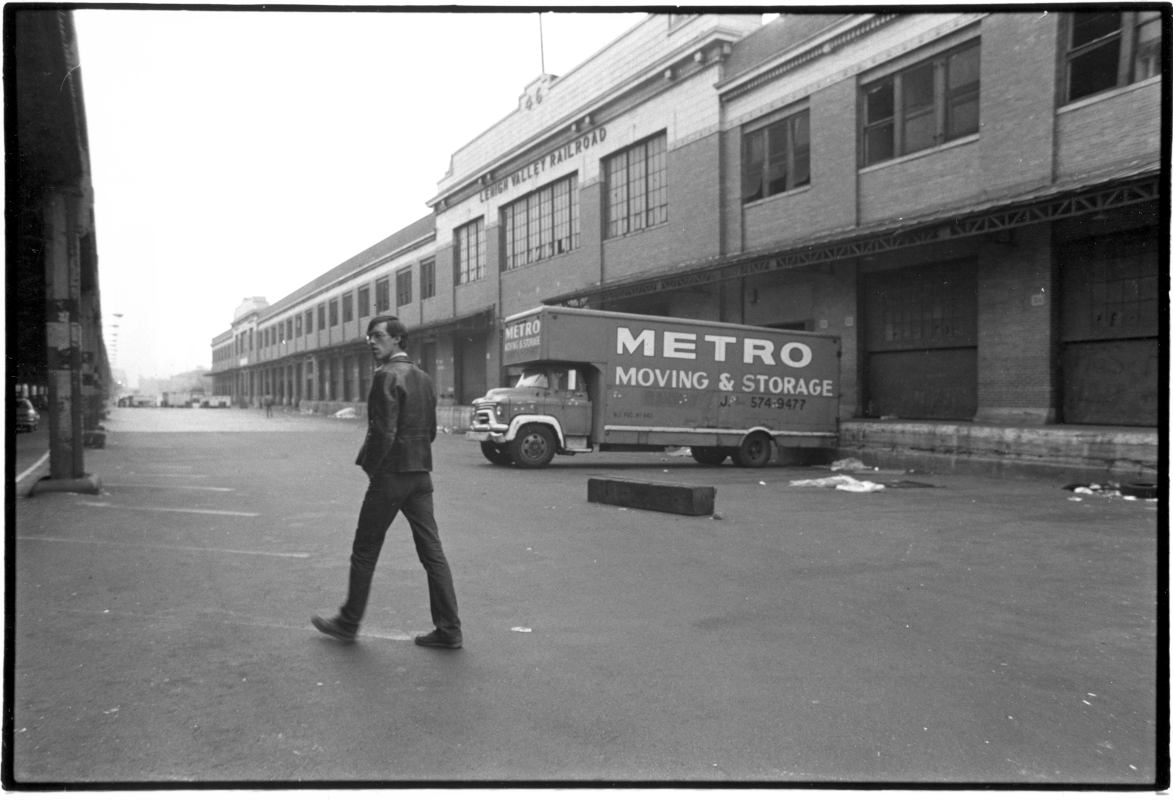

Changes in the maritime industry and the growth of the airlines made the piers and the large shipping terminals obsolete, leading them to be abandoned by the mid-1960s. This enabled the area to retain its popularity for gay men to cruise and have sex at night. A 1966 guidebook states “Go to the piers…between the trucks…” referring to the trucks that were parked at night under the elevated West Side Highway. They were used for commerce during the day, but were empty and unlocked at night, becoming a popular locale for public sex through the early years of the AIDS epidemic.

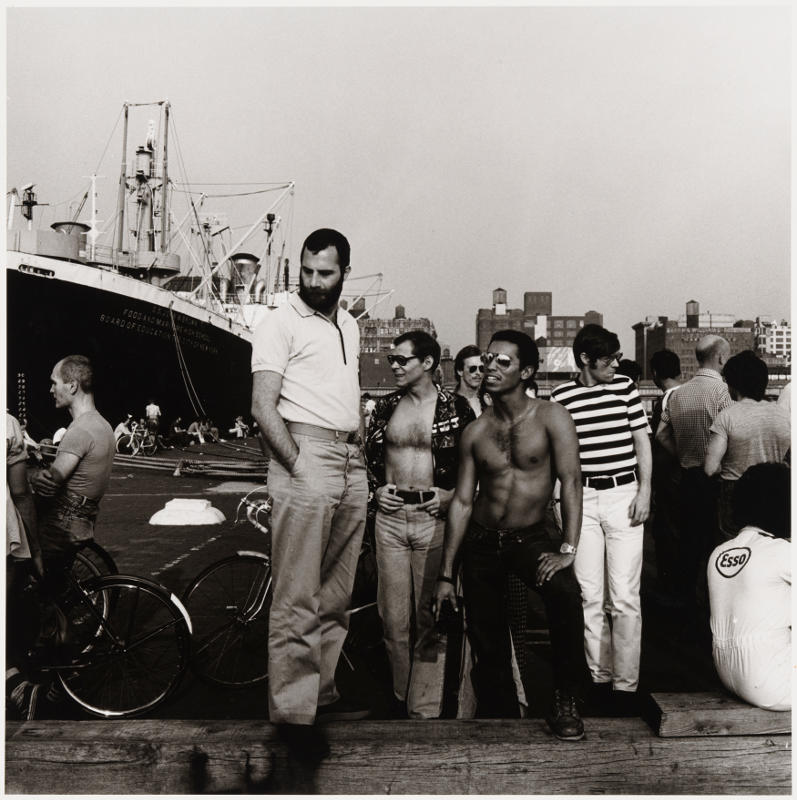

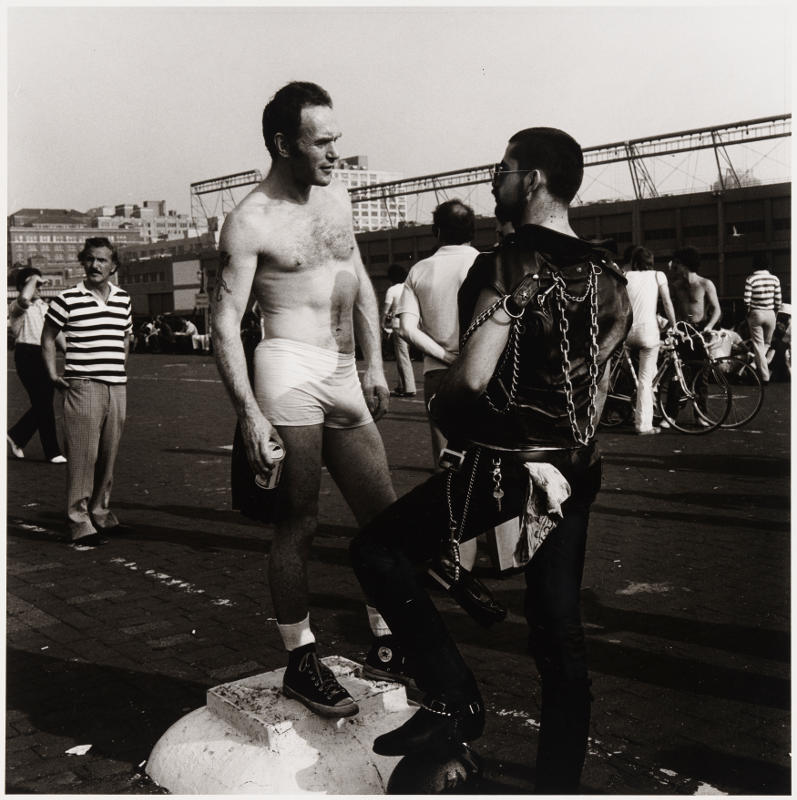

Around the time of the June 1969 Stonewall uprising, Christopher Street became an important gay thoroughfare and, thus, the main corridor to the waterfront. The dilapidated structures – including Pier 45 (known as the Christopher Street Pier) opposite West 10th Street, and piers 46, 48, and 51 – were reappropriated as a destination for gay men to sunbathe naked, cruise, and have public sex by the early 1970s.

Gay bars replaced former waterfront taverns on the western end of Christopher Street and adjacent blocks. Six of the 14 buildings in the adjacent New York City Weehawken Street Historic District housed gay bars from the early 1970s to the present, including the location of the former Ramrod. Waterfront hotels that once served seamen were converted to new uses. The ground floor of the former Keller Hotel (Barrow and West Streets) housed the Keller Bar, which was reputed to be the oldest gay “leather bar” in the city from 1956 to 1998. The former American Seamen’s Friend Society Sailors’ Home and Institute (now The Jane), at Jane and West Streets, subsequently became a transient hotel and theater venue; Hedwig and the Angry Inch had its Off-Broadway premiere here in 1998.

Many of those places that were seamen’s bars and longshoremen’s bars became gay bars. … And the piers, as they became vacant and decayed, became a kind of urban wilderness [for cruising].

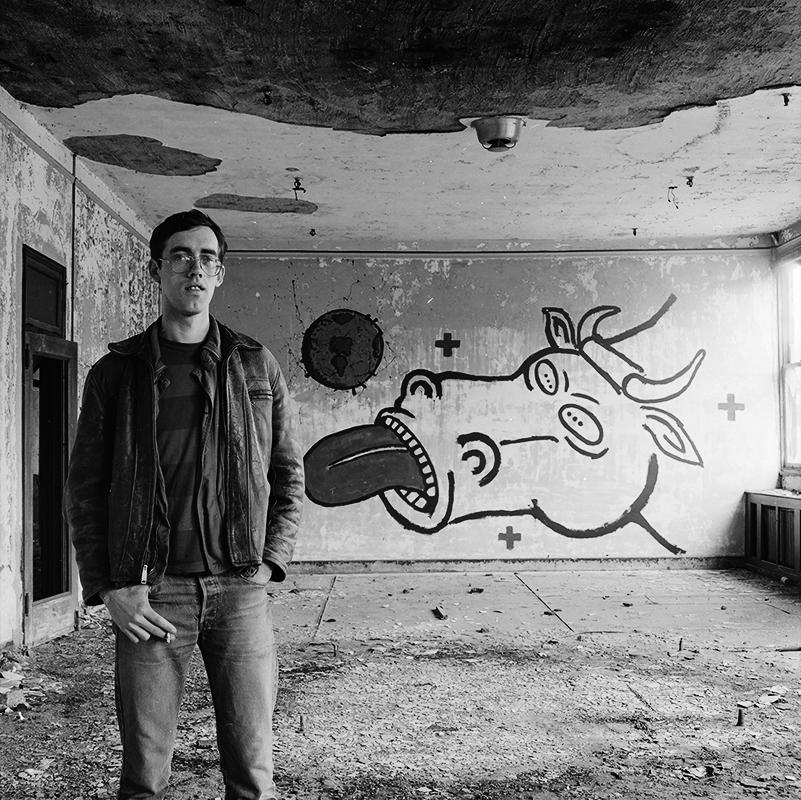

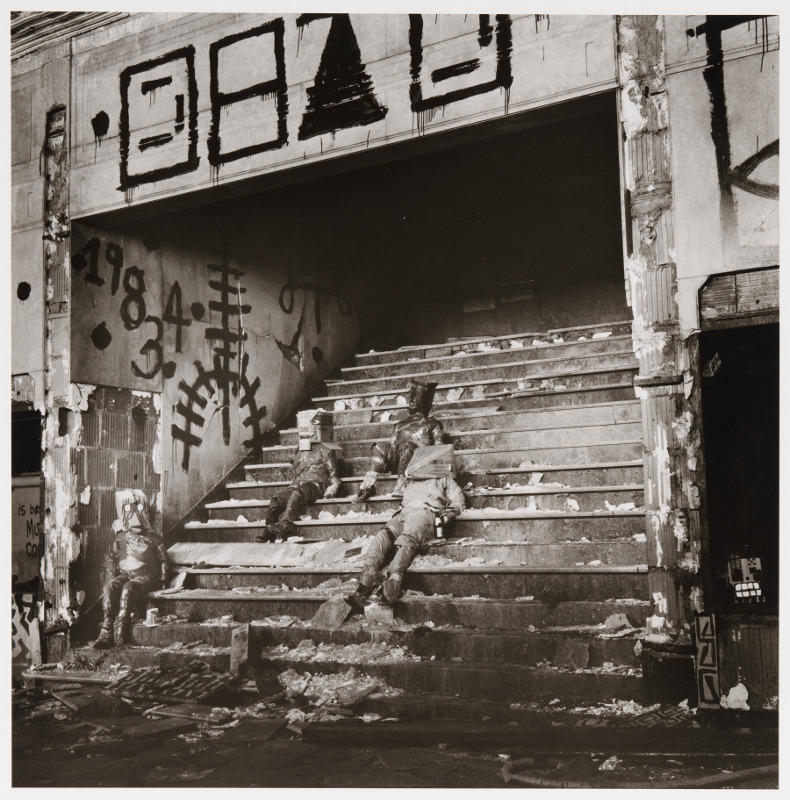

Between 1971 and 1983 the vast interiors and offices of the piers’ ruin-like terminals were the site of a diverse range of artistic work, including site-based installations, photography, murals, and performances. From 1975 to 1986, Black photographer Alvin Baltrop took photos of gay men cruising among the ruined architecture. Artist David Wojnarowicz regularly visited the piers beginning in the late 1970s, creating artworks and taking photographs there over the next few years. Wojnarowicz sent out an open invitation for an “artists’ invasion” of Pier 34 in 1983, organized with fellow artist Mike Bidlo. After painting murals on several walls on the abandoned pier, Wojnarowicz declared “This is the real MoMA.” Peter Hujar would photograph many of the murals, by Wojnarowicz and others, and took beautiful images of men socializing at Christopher Street pier, which captured the joy and sense of community that could be found there. Works by other artists, many LGBT, included Gordon Matta-Clark, Selly Seccombe, Tava, and Arthur Tress.

The AIDS epidemic and planning for waterfront improvements began to impact the area in the 1980s. By the time the Christopher Street Pier terminal was demolished in the mid-1980s, it had become a safe haven and first or second home for many marginalized queer youth of color, who to this day make up a significant percentage of the homeless youth population in New York City.

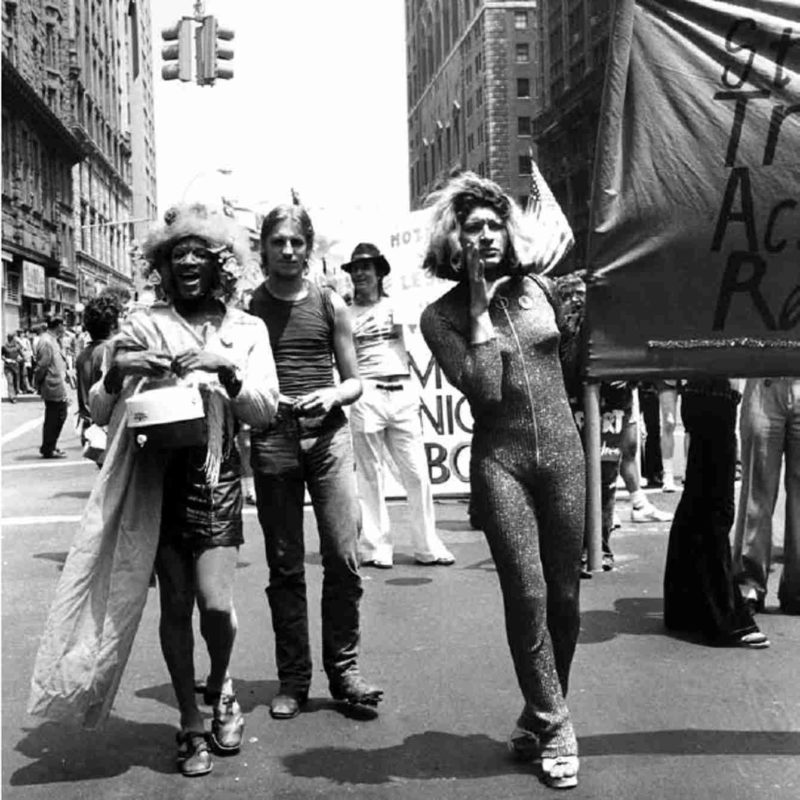

Trans activists of color Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, founders of Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) in 1970, established a presence in the area and provided food and clothing to the homeless queer youth living and congregating there. (In 2005, the intersection of Christopher and Hudson Streets, three blocks from the pier, was renamed Sylvia Rivera Way.) The 1990 documentary Paris is Burning documents the significance of the pier and this area for LGBT and questioning youth. In July 1992, Johnson’s body was found floating at the end of the Christopher Street Pier. Although the police initially called it a suicide, friends of Johnson and others in the community insisted that this was not possible, and several people had seen a group of “thugs” harass Johnson before her death.

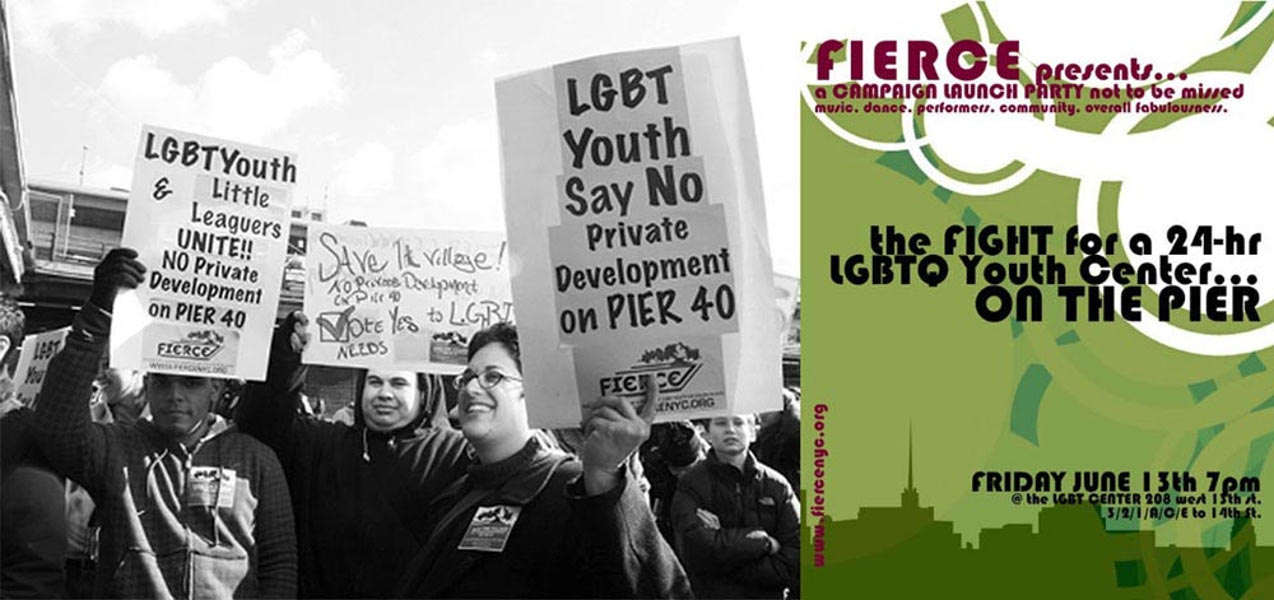

In the early 1990s, planning was underway for the rebuilding of the waterfront, including the Christopher Street Pier (which would become Hudson River Park), stretching from the Battery to Chelsea. The initial planning process did not address the presence and needs of the queer community, which catalyzed a grassroots effort. The battle for LGBT representation continued for years, including the 1998 “Queer Pier” fight to save the pier as a space for the queer youth community.

In response to the lack of representation in the planning process, the Fabulous Independent Educated Radicals for Community Empowerment (FIERCE) was founded in 2000 by a group of primarily LGBTQ youth of color. One goal was to assist with community organizing to ensure that the needs of queer youth would be addressed with the renovation of the Christopher Street Pier and the gentrification of the West Village. FIERCE created a film documenting its efforts to save the pier.

The pier was closed in 2001 and reopened in 2003 as part of the renovated section of the Greenwich Village waterfront. New restrictions were in place including a 1:00 a.m. closing that had previously not existed. Since then FIERCE has become a force helping queer youth advocate for later hours and better social services in the area.

While the waterfront and piers have limited historic physical reminders of its LGBT past, they remain important public spaces for LGBT people, especially queer youth and queer young adults of color.

Entry by Ken Lustbader, project director (March 2017).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Sources

Carl Swanson, “Manhattan’s West Side Piers, Back When They Were Naked and Gay” New York Magazine (November 18, 2015), nym.ag/2faEVSy.

George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 (New York: Basic Books, 1994).

Jay Shockley, Weehawken Street Historic District Designation Report (New York: Landmarks Preservation Commission, 2006).

Jonathan Weinberg, “City-Condoned Anarchy” Leslie Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art Exhibition Essay (April-May 2012), bit.ly/2f1rwMt.

Jonathan Weinberg, “Cruising the Waterfront” Art in America (May 1, 2015), bit.ly/1LC8VhI.

Petronius (pseud.), New York Unexpurgated (New York: Matrix House, 1966).

Queer Pier, Forty Years A Project of FIERCE, bit.ly/2fUPdb0.

Wayne Hoffman, “The Great Gay Way,” Village Voice, June 14, 2004.

Will Kohler, “Homo History – Sex: Christopher Street, the Trucks, and the West Side Highway Piers A Sexual Wonderland,” Back2Stonewall (July 1, 2016), bit.ly/2fMtmmI.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?