Anti-Police Brutality Protest in Response to the Blue’s Bar Raids

overview

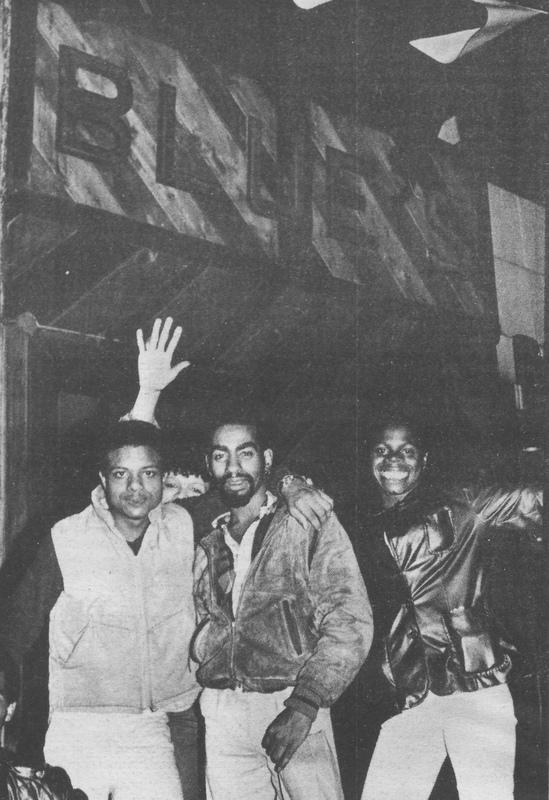

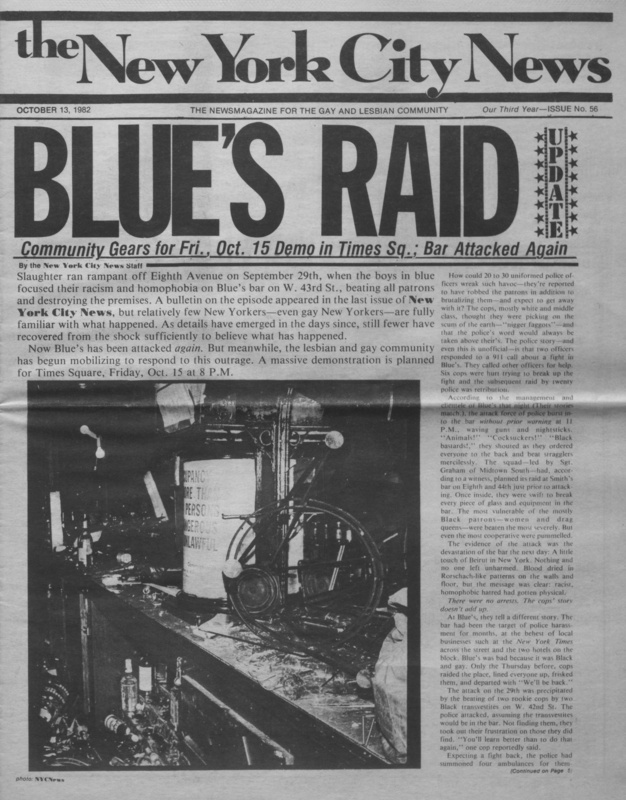

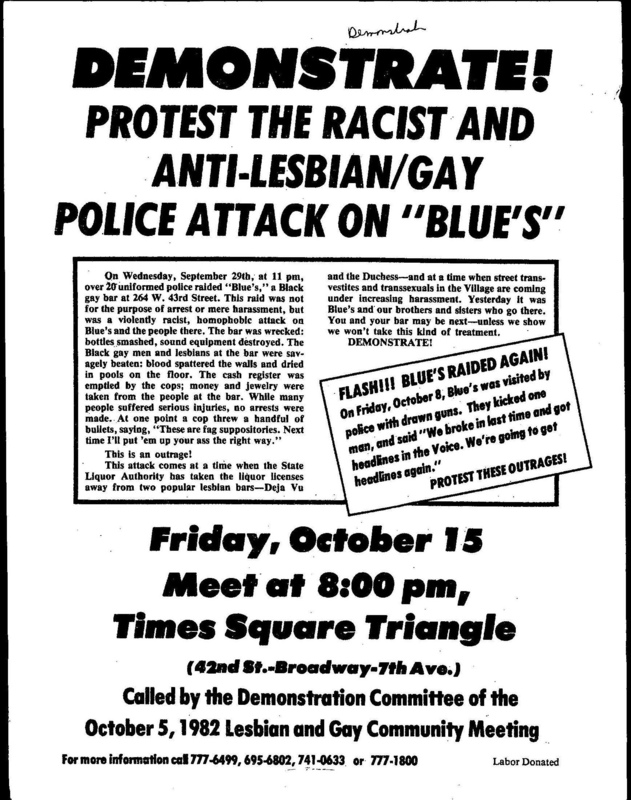

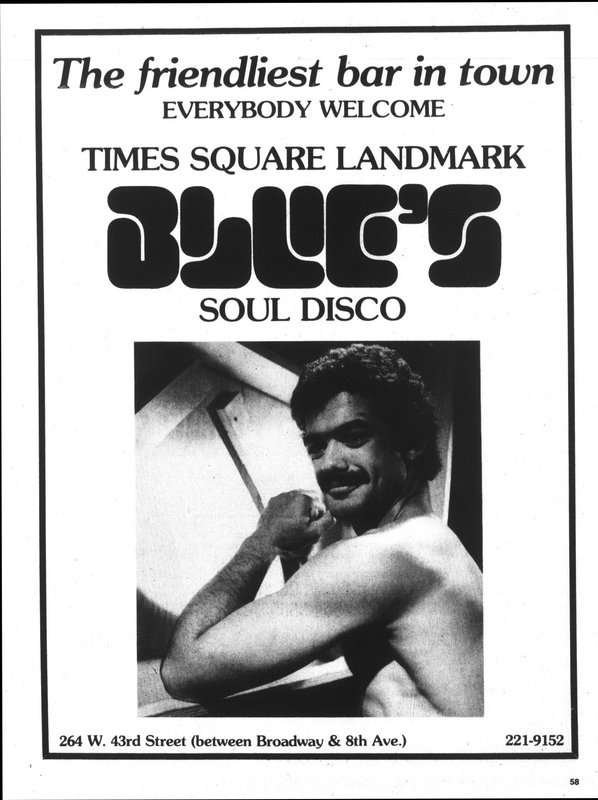

In 1982, as policing of Times Square intensified and plans to redevelop the area began to make headway, the police twice raided Blue’s, a predominantly working-class Black and Latino gay bar that also attracted lesbians and trans people.

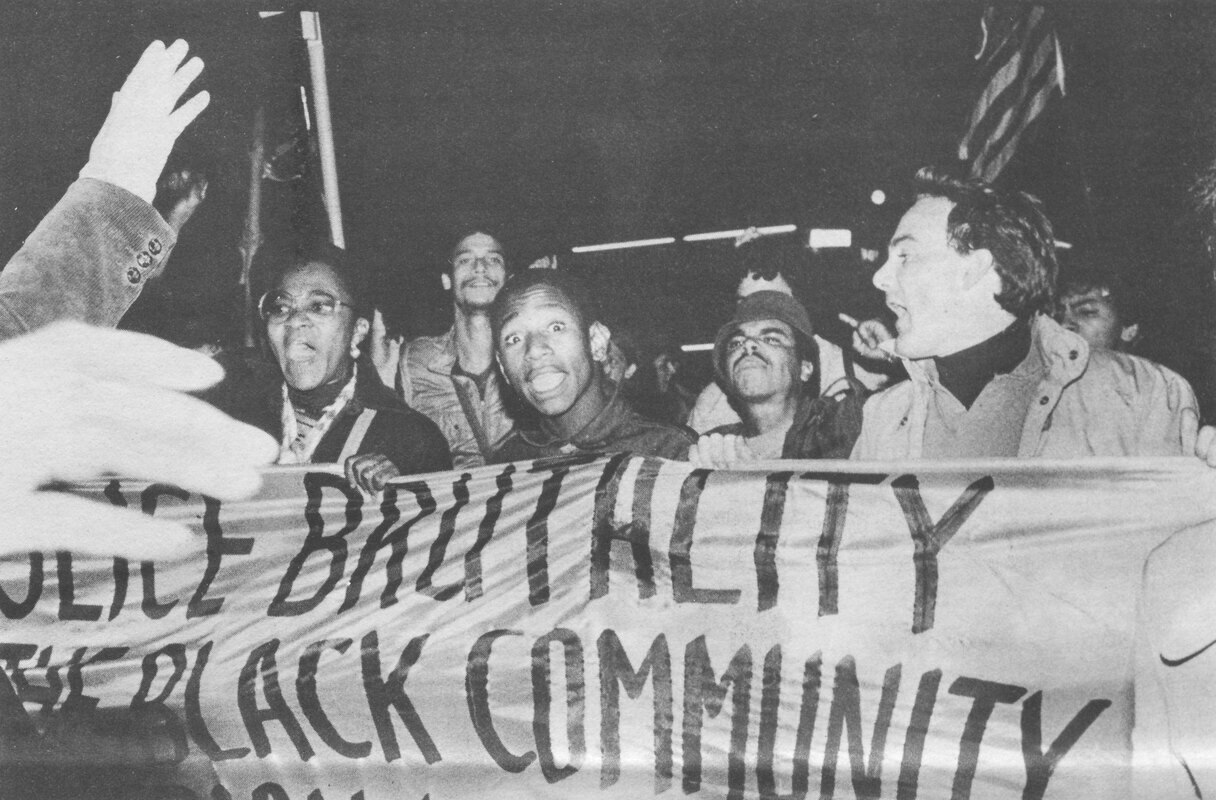

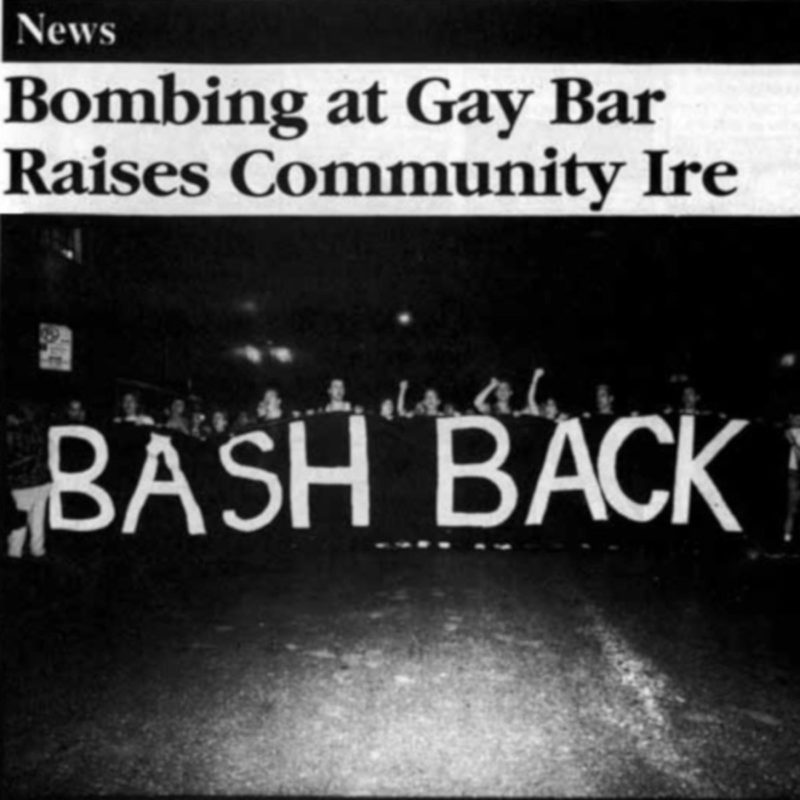

In response to the raids, arguably the last LGBT bar raids in New York City’s history, a coalition of interracial LGBT groups organized an anti-police brutality protest in the Times Square neighborhood to call out the media’s silence and condemn the raids as a racist, homophobic effort at moral cleansing and gentrification.

History

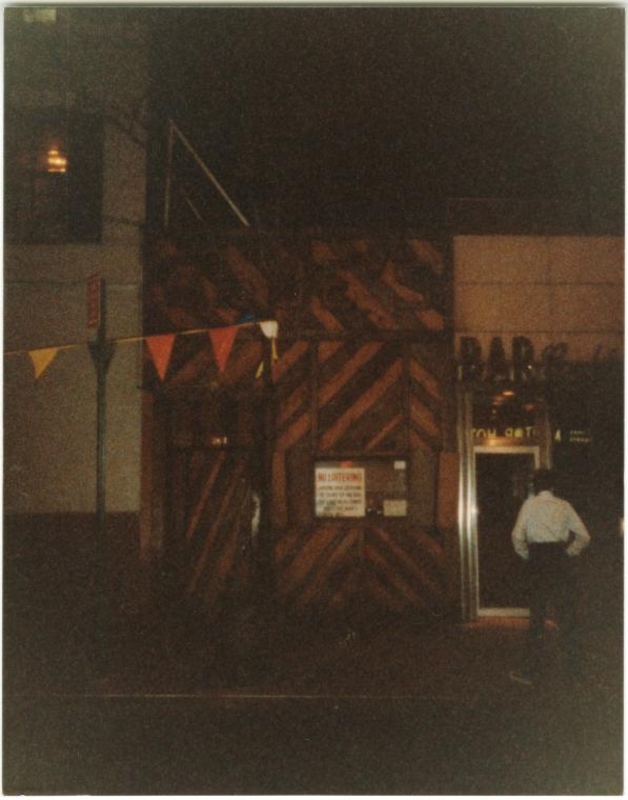

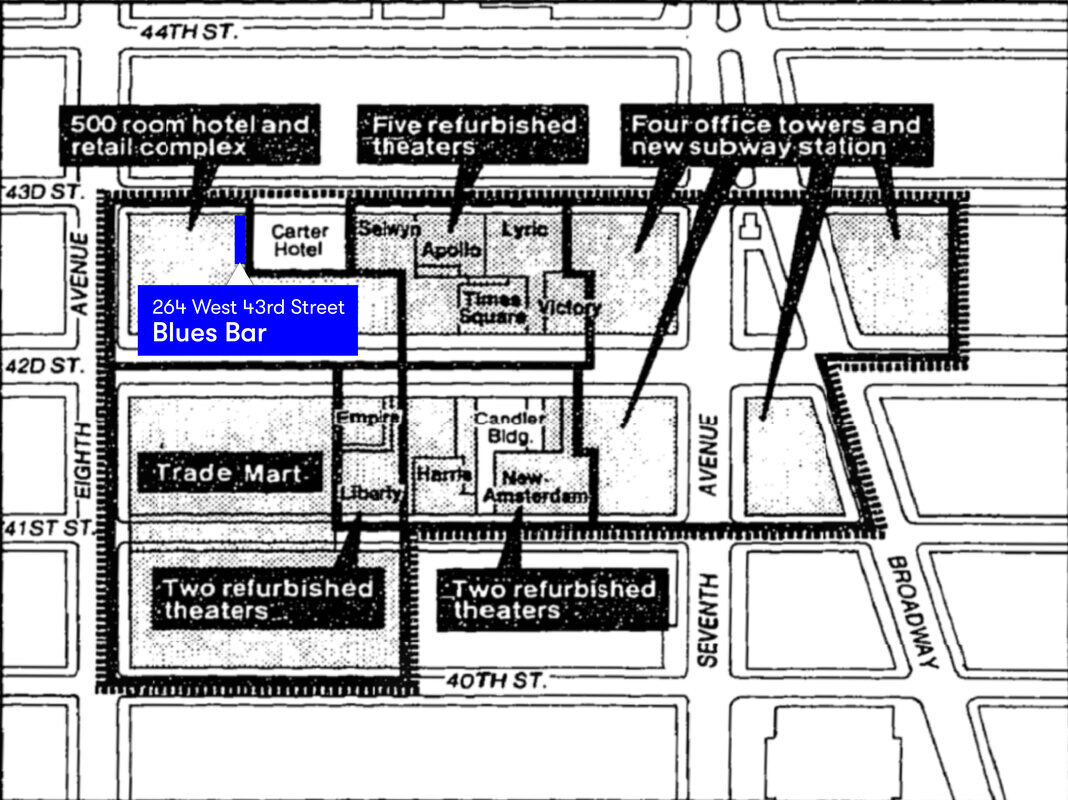

Throughout the 20th century, the city recurrently used raids, police sweeps, and other aggressive tactics to “clean up” Times Square, a red-light district and gay enclave that was increasingly viewed as seedy and tawdry. Despite a 1970 protest by the Gay Activists Alliance against such tactics, police harassment persisted in the area into the 1980s. Concurrently, the large-scale demolition and redevelopment of Times Square into a family-friendly tourist destination entered a critical phase in April 1982 when Mayor Ed Koch and the New York State Urban Development Corporation unveiled the 42nd Street Redevelopment Plan. Amid these renewal efforts, police raided Blue’s, a Black and Latino LGBT bar that opened around 1980 in a single-story building at 264 West 43rd Street (demolished), which gay bars Walter’s Pub and The Den previously occupied.

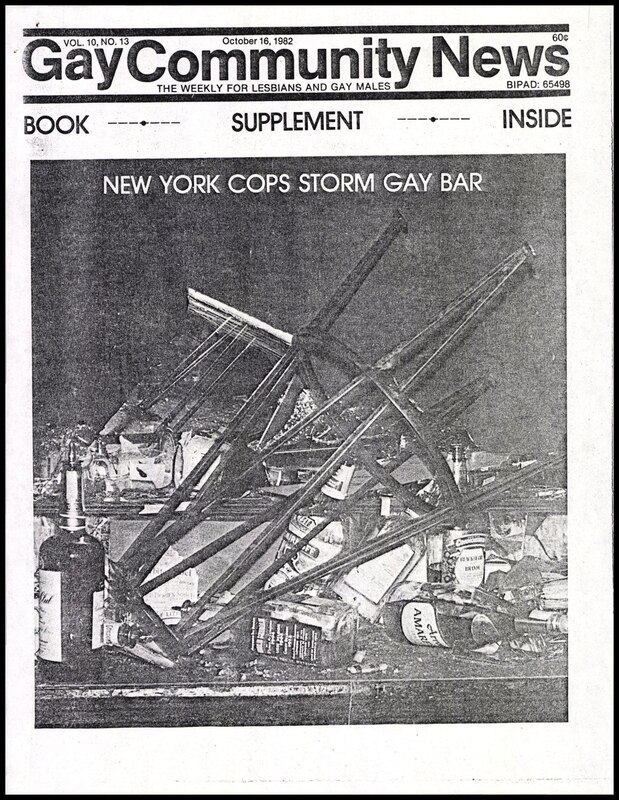

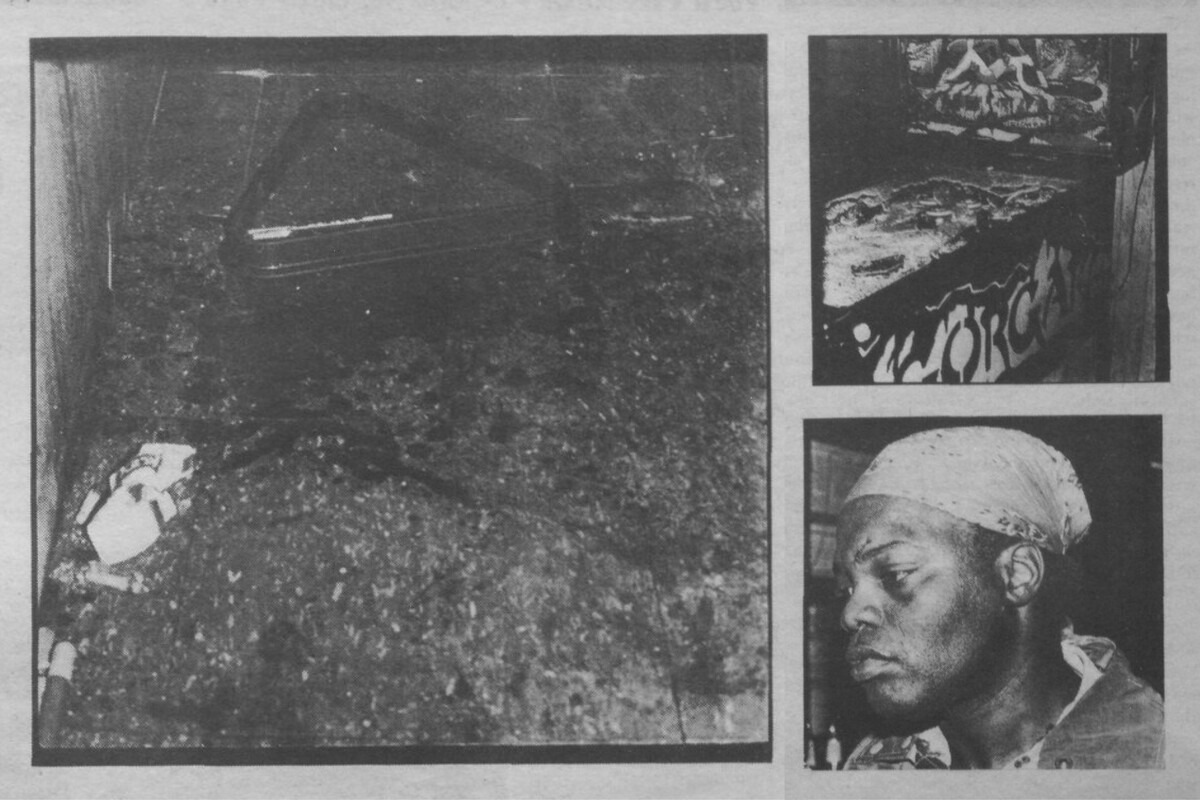

On September 29, 1982, at 11:00 p.m., around 40 uniformed officers entered Blue’s, locked the doors, and instructed patrons and employees to line up with their hands against the rear wall. Officers shouted homophobic and racist slurs, then proceeded to indiscriminately beat them — “the women the hardest, then the drag queens, then the more effeminate men,” according to on-duty manager Lew Olive. In addition to hospitalizing 12 people, the police stole jewelry and money, destroyed IDs, and inflicted $40,000 in damage. At a 1983 congressional hearing on police misconduct, Black veterans’ and LGBT rights activist James Credle described the damage:

I have never seen such destruction since my days in Vietnam….Broken bottles, glasses, and mirrors were strewn about the floor….The DJ booth was dismantled, with records broken, turntables busted, and speakers destroyed. Blood was everywhere, splattered on the floors, on the walls, on equipment — a total wasteland.

Officers variously claimed they were responding to a call about a fight in Blue’s or a reported assault, but they made no arrests and were shouting, “Don’t be beating on cops!” Therefore, many victims suspected that police raided Blue’s as retaliation against a Black trans individual who, in Times Square the previous night, had gotten into a physical altercation with an officer after resisting his “move on” order.

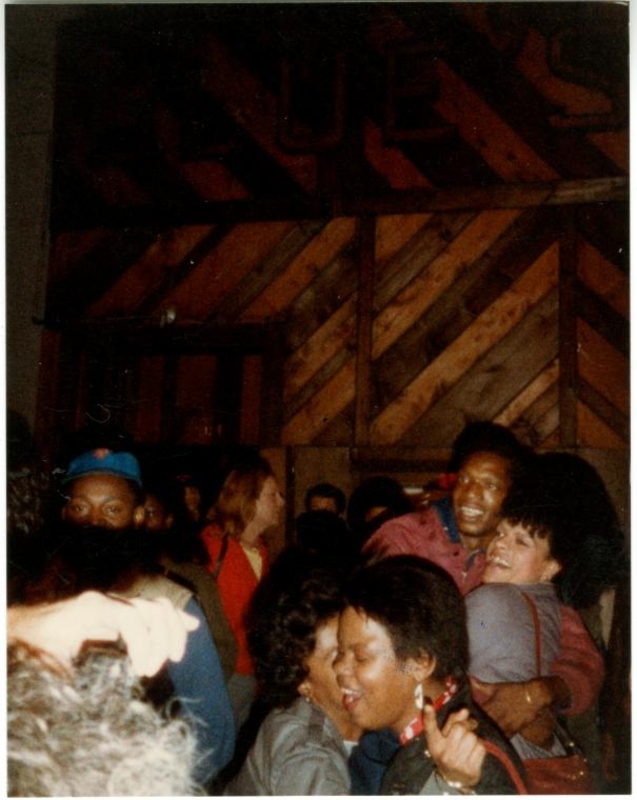

As news of the raid spread, interracial LGBT groups met at the Manhattan Developmental Center at 75 Morton Street (demolished) and at 208 West 13th Street, the former Food and Maritime High School (later the LGBT Community Center) that Metropolitan Community Church was renting, to plan a demonstration, which gained momentum after police raided Blue’s again on October 8 to allegedly search for a man with a gun. Groups involved included Black and White Men Together (now Men of All Colors Together), Coalition Against Racism, Anti-Semistism, Sexism, and Heterosexism (CRASH), Dykes Against Racism Everywhere, El Comité Homosexual Latinoamericano, Harlem Metropolitan Community Church (HMCC), Lesbian & Gay Youth, Metropolitan Community Church of New York, Salsa Soul Sisters, Third World Lesbian and Gay Alliance, and LGBT caucuses of communist and socialist parties.

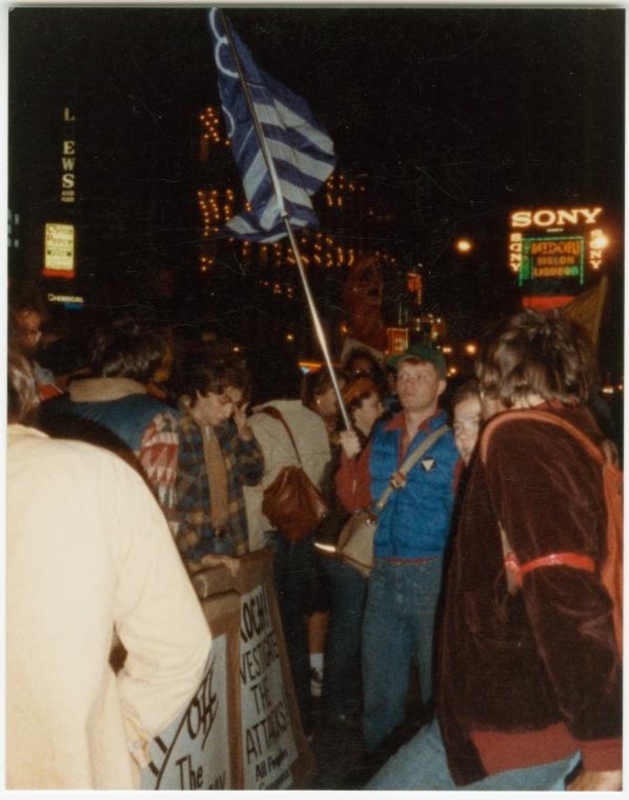

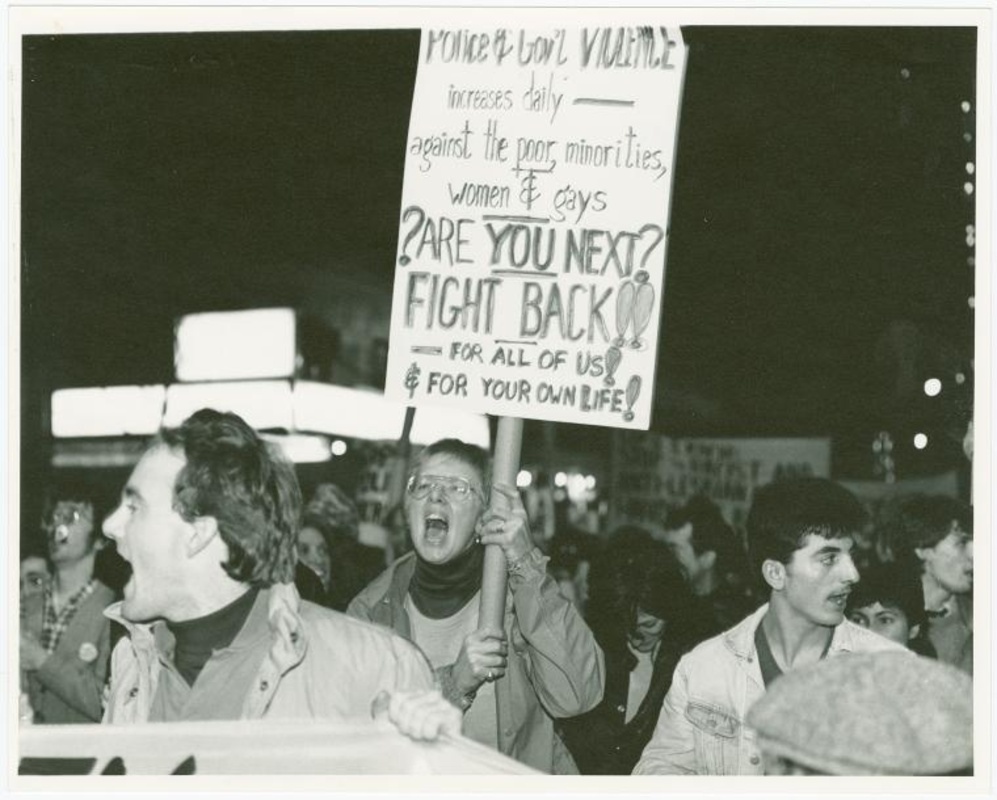

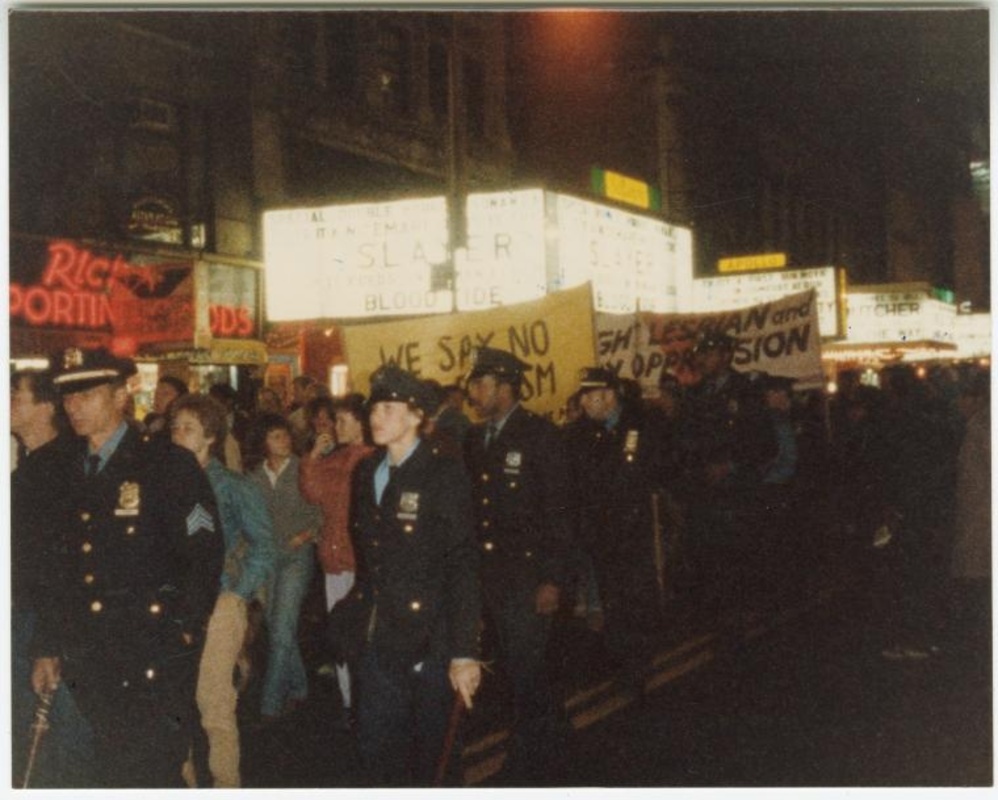

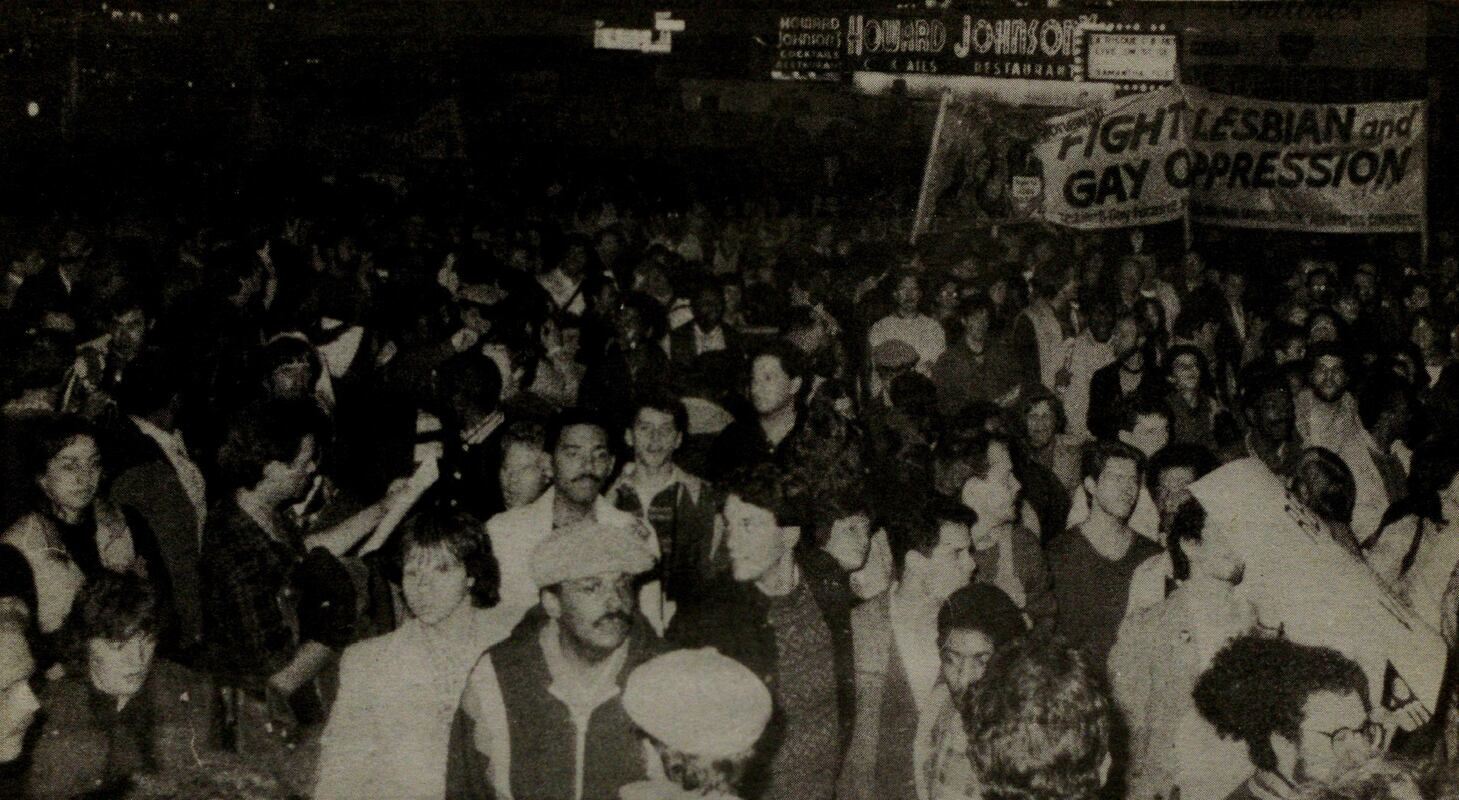

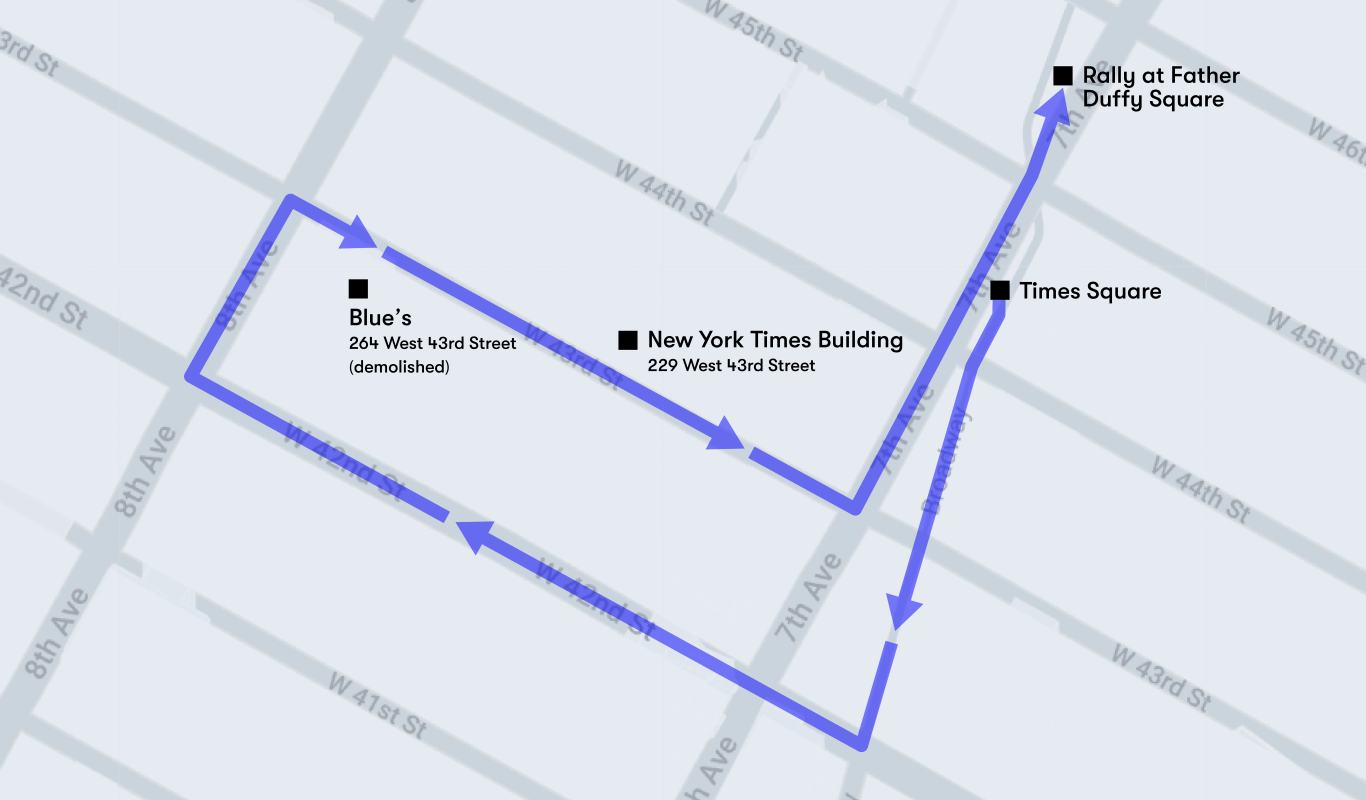

On the evening of October 15, around 1,500 protesters — many holding posters created that day in Blue’s — gathered around a traffic island (now pedestrianized) at Broadway and West 44th Street. After Gwendolyn Rogers and Reverend Magora Kennedy gave speeches outlining the coalition’s demands and likening Blue’s to Stonewall, they and a police contingent headed by openly gay Sergeant Charles H. Cochrane led protesters south on Broadway, west on 42nd Street, north on Eighth Avenue, and east on 43rd Street.

When passing Blue’s, protesters referenced the arrest threats patrons had repeatedly received for standing outside by chanting, “Out of the bars and into the streets!” They then stopped at the headquarters of The New York Times, which was then located across from Blue’s at 229 West 43rd Street, to denounce the newspaper’s failure to cover the raid and its role as a potential catalyst. Times employees had repeatedly complained about Blue’s, and the newspaper had targeted the neighborhood’s LGBT community before: management met with police in 1969 to institute, as the Times reported, “a crackdown on drunks, homosexuals, and other undesirables.”

Protesters then marched to Father Duffy Square for a rally timed to coincide with exiting theater crowds. Speakers included victims and numerous activists, who depicted the destructive raid as a racist, homophobic attempt at moral cleansing and at easing redevelopment. Although speakers focused on Blue’s, some connected the raid to the recent police beating and arrest of Black lesbian Robin Porter in Washington Square Park and the revocation of liquor licenses at lesbian bars the Duchess and Deja Vu (formerly Kooky’s). Per reporters, the most commanding speaker was Reverend Dr. Renee McCoy of HMCC, who underscored racism as the motive:

It is vitally important that we see the significance of an attack on a Black gay and lesbian bar. If racism were not the bottom line, any gay bar would have worked.

McCoy pleaded for “more dialogue within our communities” to combat authorities’ attempts to fragment them, then concluded, “If we dare to love one another through oppression and into liberation, we will someday be free.”

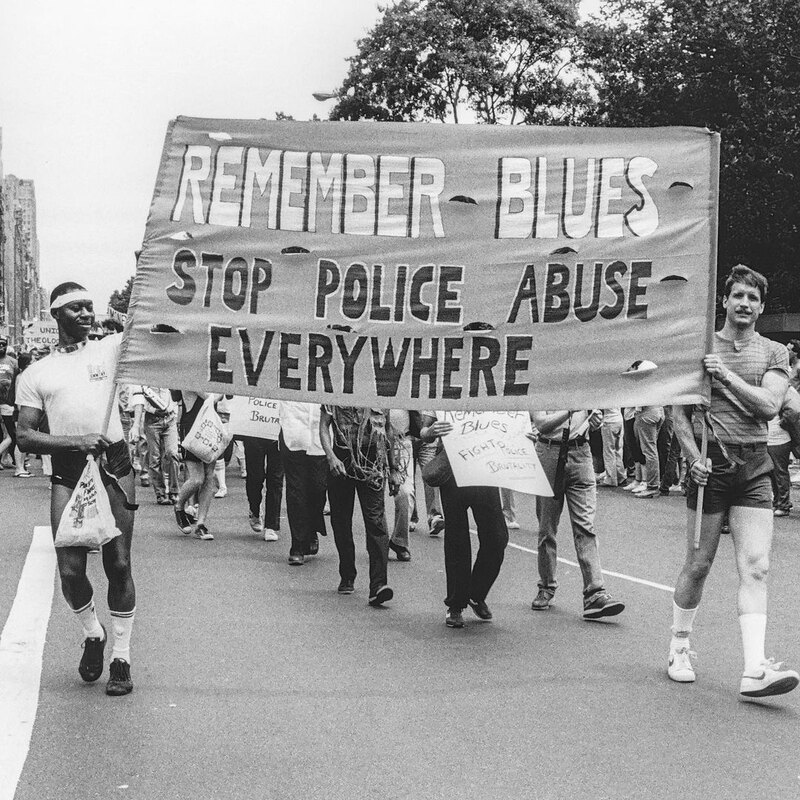

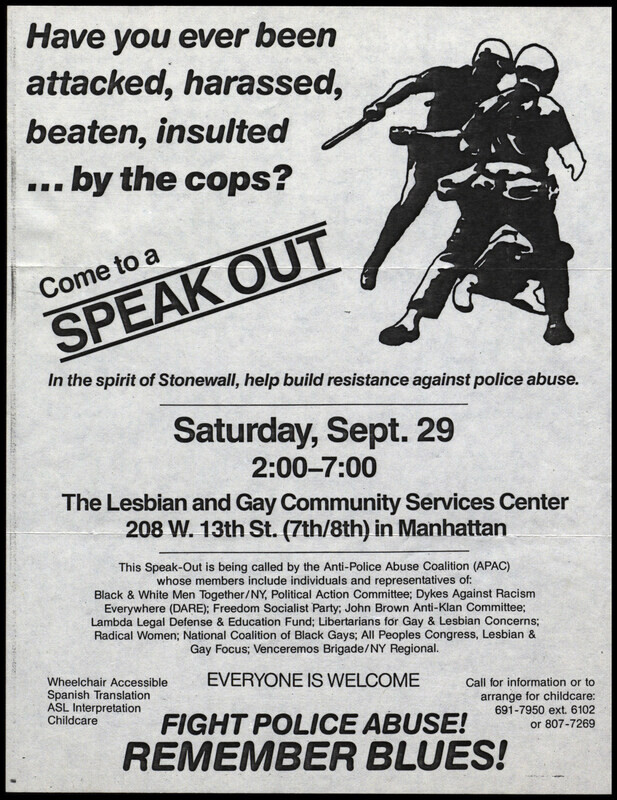

Following the protest, Blue’s remained a rallying point for many activists. The Christopher Street Liberation Day Committee cited Blue’s when it selected the theme “Diversity is Our Strength, Liberation is Our Fight” for the 1983 Pride March and reversed the route to “immobilize” the city. For years, marchers carried placards reading “Remember Blue’s,” a phrase also used by the Anti-Police Abuse Coalition, which groups involved in the demonstration established in 1984 to demand “accountability and community control of the police.”

Despite multiple investigations, no officers were charged for the raid. However, Blue’s attorney and City Human Rights Commissioner Jim Levin reported in December 1983 that Blue’s owners “now find the police helpful rather than harassing” and that LGBT bars citywide had been free of harassment since the raid. By 1986, Blue’s closed and Sally Maggio reopened the space as Sally’s Hideaway, a drag bar which operated there until a fire in 1992. By 1994, the New York State Urban Development Corporation, in partnership with the City’s 42nd Street Development Project, acquired and demolished the building and adjacent properties for the eventual Westin Hotel.

Entry by Ethan Brown, project consultant (February 2023).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Sources

Andy Humm, “Blues Demo: We Respond,” The New York City News, October 27, 1982.

Beau Lancaster, “The history missing from the LGBTQ story told during Pride month,” The Washington Post (accessed December 26, 2023), wapo.st/41zpysd.

Bob Nelson and Peg Byron, “Demo Supports Victims of Raid on N.Y. Bar,” Gay Community News, October 30, 1982. [source of second pull quote]

Christina B. Hanhardt, “Broken Windows at Blue’s: A Queer History of Gentrification and Policing,” Policing the Planet: Confronting Broken Windows Policing from New York to London to Ferguson and Beyond (London and New York City: Verso Books, 2016), 41-62.

Eric Lerner, “Militant Blue’s Rally Draws 1,100,” New York Native, November 8-21, 1982, 8. [first McCoy quote]

George Chauncey, Jr., “The Policed: Gay Men’s Strategies of Everyday Resistance,” Inventing Times Square: Commerce and Culture at the Crossroads of the World (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1991), 315-328.

Harriet Hirshorn, “Third World, Lesbian, and Gay Forces Unite at Blue’s Demonstration,” WomaNews, November 1982.

James Credle, Statement to Subcommittee on Criminal Justice of the House Judiciary Committee, Police Misconduct Hearings, 98th Cong., 1983. [source of first pull quote]

Jim Levin, “Blues: Bottom Line,” The New York City News, December 14, 1983.

“Police Begin Times Sq. Cleanup After Night Workers Complain,” The New York Times, February 6, 1969, nyti.ms/4b3xwhF.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?