Amaza Lee Meredith Residence

overview

From 1926 to 1930 and 1934 to 1935, Amaza Lee Meredith, an educator and, later, one of the first Black woman architects, stayed with her sister’s family in this Harlem rowhouse while she attended Teachers College, Columbia University.

Meredith’s exposure to New York City’s art and culture had a profound impact on her and her work, including her now-renowned design for Azurest South, the house in Petersburg, Virginia, that she shared with her partner, leading Black educator and activist Edna Meade Colson.

On the Map

VIEW The Full MapHistory

Amaza Lee Meredith (1895-1984) was born and raised in Lynchburg, Virginia, the daughter of a Black mother and a white father and the youngest of four children. In the 1890s, her father, a skilled carpenter, built them a large house on the edge of the city. It is unclear if her father lived with them – interracial coupling would remain illegal in Virginia until 1967 – but he did spend time there. (Her parents eventually married in 1902, likely doing so by traveling to Washington, D.C., where their union was legal.) Meredith’s father taught her his craft, modelmaking, and how to draw blueprints. He, however, discouraged her interest in an architecture career, perhaps knowing the hardships she would face because of her race and gender.

Meredith’s mother pushed her to pursue her education. In 1915, after graduating at the top of her high school class, Meredith enrolled at Virginia Normal and Industrial Institute (VNII) in Petersburg that summer and met Edna Meade Colson (1888-1985), one of her teachers. Historian Jacqueline Taylor notes in Suffragette City, “Meredith fell in love with learning and with her instructor. Colson made it clear that she reciprocated her student’s romantic feelings, and they began a sporadic but long-term love affair.” Sporadic because Meredith was often away from Petersburg to further her teaching credentials, though they kept in touch through frequent letters.

Colson, a staunch advocate for improving educational opportunities for African Americans in the Jim Crow era, encouraged Meredith to go north to continue her professional development. In 1926, she enrolled at Colson’s alma mater, Teachers College, Columbia University. Meredith moved into the large rowhouse at 416 West 146th Street in the Sugar Hill section of Harlem, where her sister, Maude Terry, a Brooklyn schoolteacher, and her family had recently taken up residence. Meredith stayed here until 1930 and again from 1934 to 1935, while she obtained her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in fine arts, respectively. Her coursework included home decoration and interior design.

Meredith’s exposure to art and culture in the city in the late 1920s and early 1930s had a profound influence on her, personally and professionally. Her letters to Colson reveal that both were drawn to the city’s newest fashions, and Meredith began wearing trousers – a non-traditional garment for women at the time – that would later define her style. Living in Harlem during the Harlem Renaissance also impacted her, and she visited at least one of its central hubs, the 135th Street Branch of the New York Public Library. Meredith also frequented the theater as well as exhibitions organized by the Architectural League, the American Union of Decorative Artists and Craftsmen, the Brooklyn Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). In 1932, she attended MoMA’s highly influential “Modern Architecture: International Exhibition,” where the term “International Style” was coined.

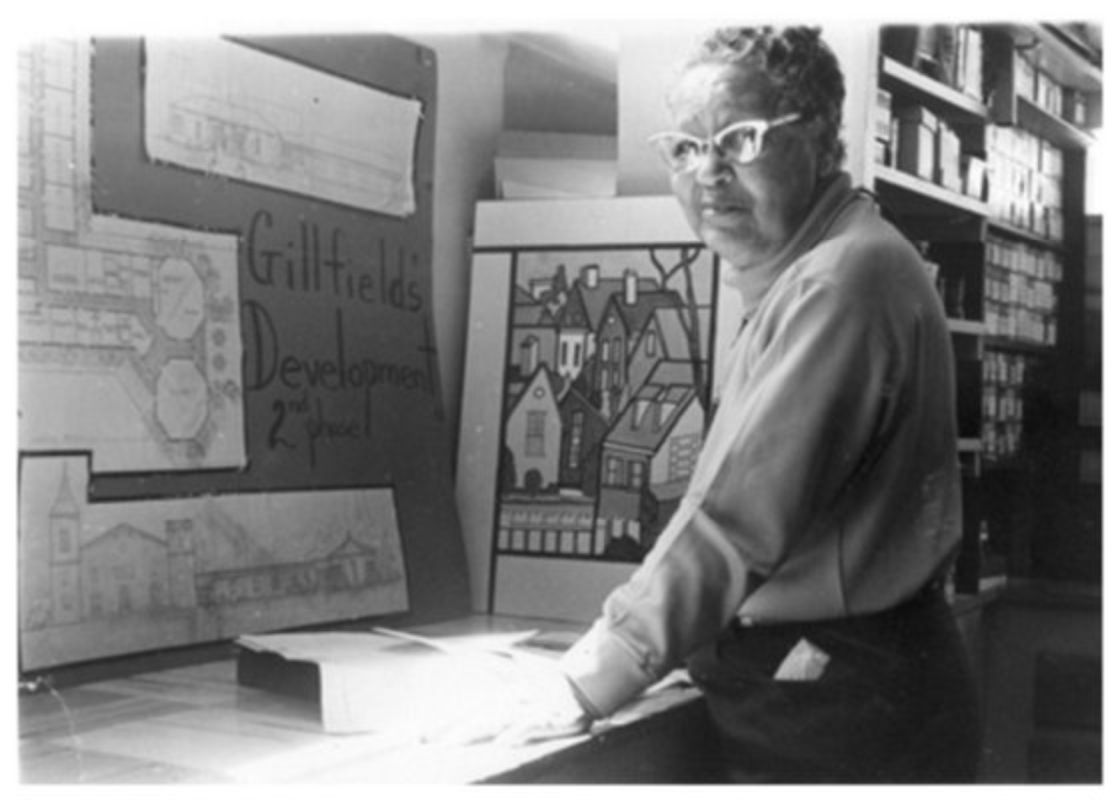

Meredith returned to her Virginia alma mater (known today as Virginia State University, or VSU) to begin her teaching career in 1930, in between her studies at Teachers College. Her experiences in New York helped inform her teaching, and she also incorporated exhibition catalogues that she collected there into her course syllabi. After receiving her Master’s degree from Teachers College in 1935, she founded VSU’s Fine Arts Department, which she led until her retirement in 1958.

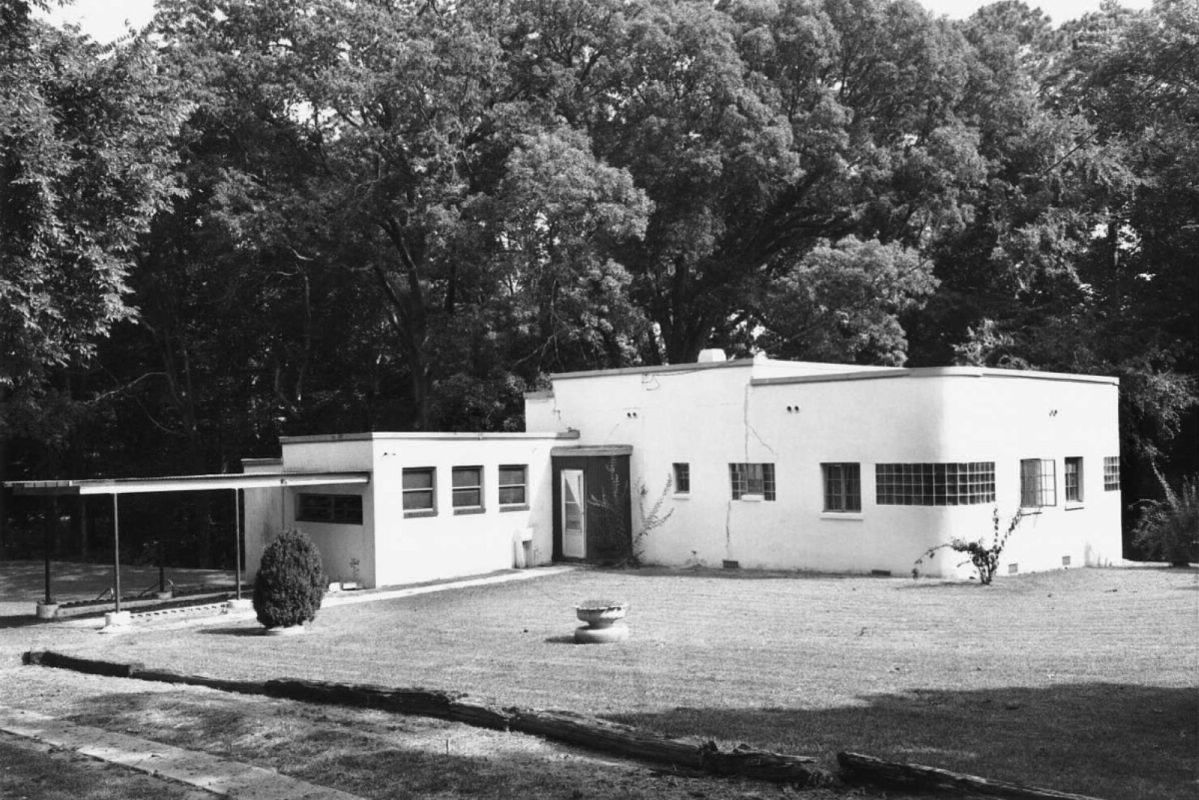

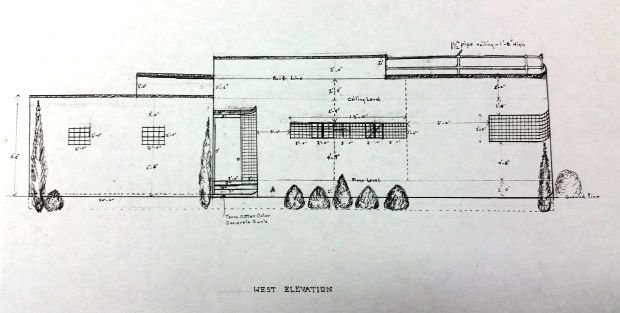

Denied the opportunity to become a professional architect because of her race and gender, Meredith nevertheless designed several residences. Her best known, Azurest South, was built on land she and Colson had purchased directly across from the Petersburg campus. Completed in 1939, the house, built in the Modernist tradition, was among the country’s earliest structures to be designed by a Black woman. As Taylor notes, in an era when homeownership was rare among African Americans, in large part because of discriminatory housing policies, “…it was bold for a black woman to build and own her own house, and this boldness was made manifest in the house’s style.” Taylor continues, “Azurest reflects the radical European modernist work she encountered studying in New York, particularly the architecture of Le Corbusier, which was featured prominently” at MoMA’s 1932 exhibition. (Meredith willed her half of Azurest South to VSU’s Alumni Association, which bought Colson’s half after her death.)

In 1947, Meredith, her sister Maude Terry, and others developed Azurest North in Sag Harbor on Long Island as a summer destination for middle-class African Americans. Meredith designed two residences there, including her family’s cottage; she and Colson shared a small bedroom, in which Meredith kept her drafting table. Azurest South was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1993 (National Historic Landmark status pending) and Azurest North was listed as part of the Sag Harbor Hills, Azurest, and Ninevah Beach Subdivisions (SANS) Historic District in 2019.

Entry by Amanda Davis, project manager (March 2023).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Neville & Bagge

- Year Built: 1883

Sources

“17 of Columbia’s 24 Graduates Get A.M. Degrees,” Afro-American, June 8, 1935, 1.

“Amaza Lee Meredith,” Columbia GSAPP, February 14, 2021 (accessed February 12, 2023), bit.ly/3TfYIBl.

“Amaza Lee Meredith,” Docomomo US (accessed February 12, 2023), bit.ly/3mVFvc3.

“Amaza Meredith (1895 – 1984),” Virginia Changemakers (accessed February 11, 2023), bit.ly/2K5D6Xt.

Amaza Lee Meredith Papers, 1912, 1930-1938, Accession #1982-20, Special Collections Department, Johnston Memorial Library, Virginia State University, Petersburg, VA.

Calder Loth, Mary Harding Sadler, and James Hill, “Azurest South,” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form (Richmond, VA: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, September 15, 1993).

Jacqueline Taylor, “Amaza’s Azurest: Modern architecture and the ‘New Negro’ woman,” in Elizabeth Darling and Nathaniel Robert Walker, eds., Suffragette City: Women, Politics and the Built Environment (New York: Routledge, 2020). [source of Taylor quotes]

Jacqueline Taylor (2014), Designing Progress: Race, Gender and Modernism in Early 20th Century America [Doctoral dissertation, University of Virginia], bit.ly/3lgGR0p.

Jessica Lynne, “‘That Which We Are Still Learning to Name:’ Two Photographs of Black Queer Intimacy,” Southern Cultures, vol. 26, no. 2, Summer 2020 (accessed February 12, 2023), bit.ly/429G4iF.

John Hughes, “Personals,” Afro-American, January 6, 1934, 8.

Mario Gooden, Dark Space: Architecture, Representation, Black Identity (New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2016).

New York Telephone Directories, 1930-1934.

Nicholas Som, “The Colorful Past and Bright Future of Azurest South, Home of a Pioneering Black Architect,” National Trust for Historic Preservation, July 14, 2021 (accessed February 12, 2023), bit.ly/3Lu84r9.

“Our History,” Virginia State University (accessed February 11, 2023), bit.ly/3JiaxSQ.

Sarah Kautz, “The Founding and Future of Sag Harbor’s Azurest Subdivision,” Preservation Long Island, February 2019 (accessed February 12, 2023), bit.ly/3ZQiB4o.

“Studying While Black During the Jim Crow Era,” Teachers College, Columbia University, January 31, 2023 (accessed February 11, 2023), bit.ly/3li5b22.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?