GAY Newspaper Offices

overview

GAY was the third post-Stonewall gay newspaper in New York City, started in December 1969 by Jack Nichols and Lige Clarke, and located in this building from 1971 to 1972.

Before ceasing publication in 1974, it was the most profitable LGBT newspaper in the U.S., and GAY’s varied content featured articles written by some of the era’s most significant LGBT rights activists, including in-depth coverage of the recently-formed Gay Activists Alliance.

On the Map

VIEW The Full MapHistory

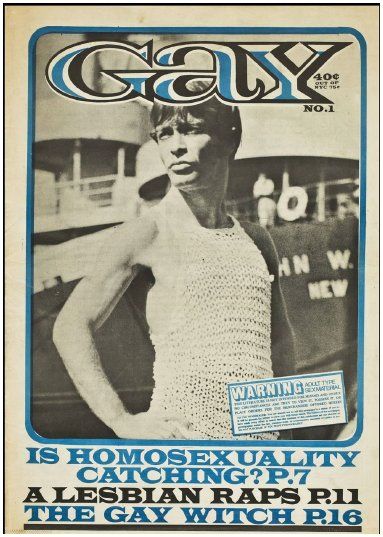

New York City’s first post-Stonewall gay newspaper was GAY POWER, published from September 15, 1969, to June 1970, with only 24 issues. The next was the Gay Liberation Front’s COME OUT!, which the group issued from November 15, 1969, until the winter of 1972. These were soon eclipsed by GAY, the creation of personal and professional partners Jack Nichols (1938-2005) and Lige Clarke (Elijah Hadyn Clarke; 1942-1975), which was first published on December 1, 1969.

Nichols was one of the co-founders of the Mattachine Society of Washington, D.C., in 1961 with Frank Kameny, and became an important gay rights activist, leader, and journalist. In 1966, Mattachine Washington started a newsletter titled “The Homosexual Citizen” which claimed to be “the movement’s first fully militant civil rights publication.” Nichols met Clarke, then in the Army, in Washington, and they became a couple.

After they moved to New York City in 1967, they both started working for a magazine publisher, where they met Al Goldstein. The couple started a column called “New York Notes” for the Los Angeles-based gay newspaper The Advocate in April 1968. In November of that year, Goldstein and Jim Buckley started Screw, a pornographic newspaper for heterosexual men. They invited Nichols and Clarke to write a column, which they called “The Homosexual Citizen.” This has been considered the first gay perspective column printed in a non-gay publication in the country; it continued until 1973.

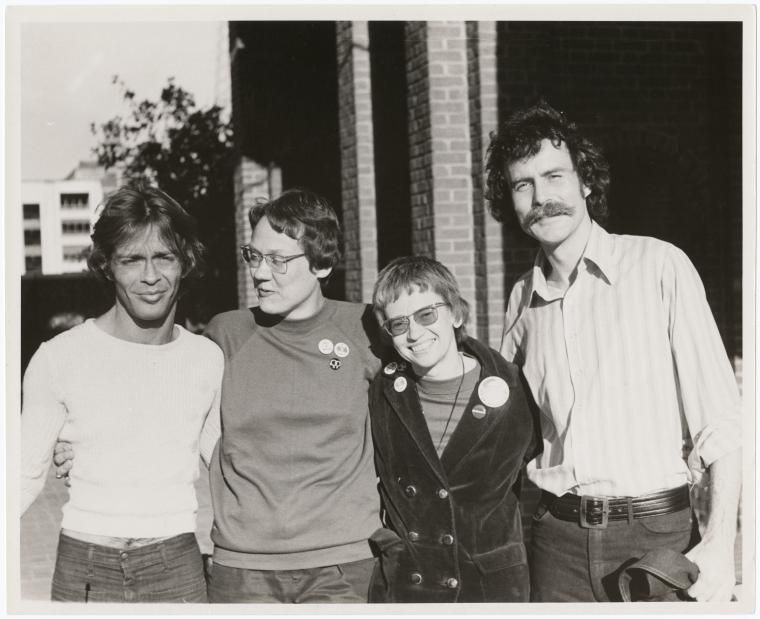

After the Stonewall uprising, Nichols and Clarke’s friend, lesbian activist Kay “Tobin” Lahusen, suggested to them that the time was right for a gay newspaper, and Goldstein and Buckley backed their creation of a separate gay newspaper. Goldstein and Buckley were further influenced by the fact that the publisher of KISS, a competitor since April 1969 of Screw, was behind GAY POWER. GAY was published by Buckley and Goldstein’s Four Swords, Inc., the company name apparently referencing the four male founders. Nichols and Clarke were the executive editors until July 1973. Lahusen was the first news editor.

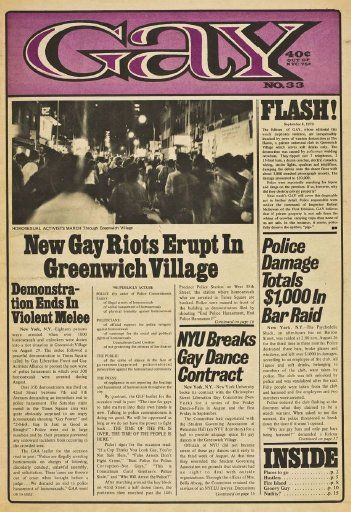

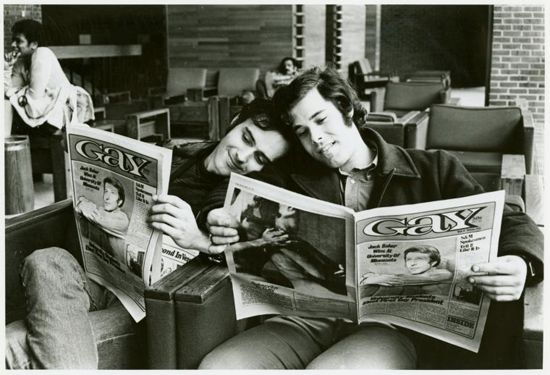

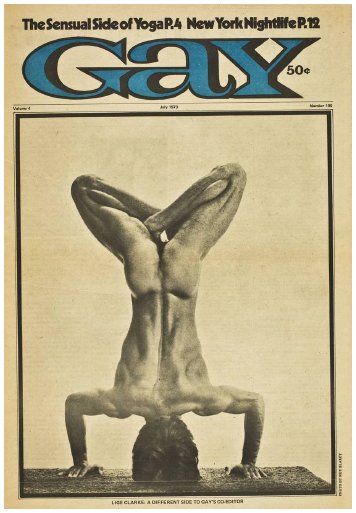

For the first year and a half, GAY used a post office box and listed no address. In the July 5, 1971, issue, 11 West 17th Street was first published as the address of its offices. The newspaper moved to 116 West 14th Street by August 7, 1972. GAY had a wide variety of articles, photographs, and artwork, and featured political news, particularly in-depth coverage of the activities of the recently formed Gay Activists Alliance (GAA), interviews, articles on sexuality, male nude photographs, history, and book, theater and film reviews. It managed to reach a broad audience and went on to become the most profitable LGBT newspaper in the U.S. in its day. It started as a bi-weekly, but from April 20 to September 28, 1970, was “America’s First Gay Weekly” and was called the first weekly gay American newspaper distributed by subscription and at newsstands. It went back to being printed bi-weekly, and at the end of its run was monthly.

As columnists, correspondents, and editors, Nichols and Clarke attracted some of the most significant individuals in the homophile and gay liberation movements. These included Mattachine Society activists Dick Leitsch, Randy Wicker, and Lilli Vincenz, and GAA activists Rich Wandel, Pete Fisher, John Paul Hudson (John Francis Hunter), Arthur Bell, Vito Russo, and Leo Skir. Contributors also included art critic Gregory Battcock, psychologist George Weinberg, Don Teal, author of The Gay Militants (1971), and Angelo d’Arcangelo, author of The Homosexual Handbook (1968). Photographs were supplied by Wandel, Lahusen, and Eric Stephen Jacobs.

In the last issue of GAY that Nichols and Clarke edited, in July 1973, they thanked “gay liberationists who have been particularly helpful” in their years with the newspaper – these included Kameny, Morty Manford, Barbara Gittings, Jim Owles, Morris Kight, and Alan Roskoff. GAY ceased publication in January 1974. Goldstein attempted to continue it with a slightly more sex-oriented focus, but the newspaper failed without its original gay editors.

Entry by Jay Shockley, project director (December 2022).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Otto Strack

- Year Built: 1907-08

Sources

“1969 The Year of Gay Liberation: Gay News,” New York Public Library, on.nypl.org/3WNYWQu.

GAY (1969-1974), Houston LGBT History, bit.ly/3C68Ghg.

Jack Nichols, “An Editor Says Goodbye,” GAY, July 1973, 12-13, 15.

James T. Sears, “Jack Nichols (1938- _): The Blue Fairy of the Gay Movement,” and Jack Nichols, “Lige Clarke (1942-1975),” in Vern L. Bullough, edit., Before Stonewall: Activists for Lesbian and Gay Rights in Historical Context (New York: Harrington Park Press, 2002), 219-240.

Lige Clarke and Jack Nichols, “Lige & Jack,” GAY, July 1973, 2.

Tracy Baim, editor, Gay Press, Gay Power: The Growth of LGBT Community Newspapers in America (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2012).

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?