Gilbert Baker & “Raise the Rainbow” Workshop

overview

Artist and activist Gilbert Baker, best known for the iconic and internationally recognized Rainbow Flag (1978), used the basement commercial space of this Chelsea high-rise apartment building as his “Raise the Rainbow” workshop from the end of 1993 to June 1994.

Visible through a window, the workshop was where Baker and a small crew sewed a mile-long Rainbow Flag, then a world record, in commemoration of Stonewall 25.

History

San Francisco-based artist and activist Gilbert Baker (1951-2017), born and raised in Kansas, became involved with the LGBT rights movement in the early 1970s. The pink triangle was then a popular symbol in the fight for gay liberation, following its adoption by activists in West Germany to address the collective silence over gay Holocaust victims and survivors (these men, arrested under Paragraph 175, which made sex between men illegal, were forced to wear a pink triangle badge on their concentration camp uniforms). Given its Nazi origins, however, its use was controversial. Baker’s friends, San Francisco filmmaker Artie Bressan, Jr. and activist Harvey Milk, suggested the creation of a new unifying symbol. As a result, Baker worked with James McNamara, Faerie Argyle Rainbow (Lynn Segerblom), and a group of about 30 volunteers to create the two original eight-stripe Rainbow Flags in 1978. The flags debuted at San Francisco’s Gay Freedom Day that June. The now-familiar six-stripe version appeared a year later.

For the Pride March associated with Stonewall 25, held in New York City in June 1994, Baker envisioned a mile-long Rainbow Flag. His friend Cleve Jones, a San Francisco-based LGBT rights and AIDS activist, secured funding for the project from Stadtlander’s Pharmacy, an East Coast-based mail order pharmacy. This sponsorship was controversial, as AIDS activists had fought for years against pharmaceutical companies profiteering from the epidemic. Jones, however, believed that he could improve access to medication by cutting through government red tape and working with independent pharmacies.

Baker moved to New York at the end of 1993, initially staying in a commune at 9 Bleecker Street, off the Bowery. The basement commercial space at 269 West 16th Street, visible through a window and part of a high-rise apartment building in Chelsea, became his “Raise the Rainbow” workshop. In anticipation of long hours of sewing, he had white linoleum floors installed to reflect more light in the space. The walls, including the pipes, were painted white and big banks of fluorescent lights ran the length of the room. He also specified the location of a staircase (still there) so that the finished flag could be transported to street level more easily. The workshop accommodated 18 “refrigerator-sized crates,” each holding a bolt of fabric and weighing 400 pounds.

Baker was joined by McNamara and Jones’s assistant, Ed, who ran the front office. Richard Ferrara, who created banners and flags for Heritage of Pride, the organizers of the NYC Pride March, was Baker’s chief assistant. (Other volunteers helped fold, tie, and transport the flag.)

I would get to the workshop at seven thirty each morning, drink coffee, and start sewing. James and Ed would roll in around ten. Richard dropped by most evenings. The four of us put in long hours, often staying late into the night.

Completed in early June, the mile-long flag, then a Guinness World Record, weighed 7,000 pounds and measured 30 feet in width. However, the project faced issues from the start. For one, Stadtlander’s had only agreed to sponsor the flag’s creation to support AIDS charities, not LGBT rights, and, according to Baker, was neither interested in the Rainbow Flag’s significance as a gay political symbol nor happy that Baker wore (handmade) dresses and was an outspoken gay activist. Furthermore, newly elected Mayor Rudolph Giuliani sided with the Archdiocese of New York and had the march route moved from Fifth Avenue to the less prominent First Avenue, so that marchers would not pass St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

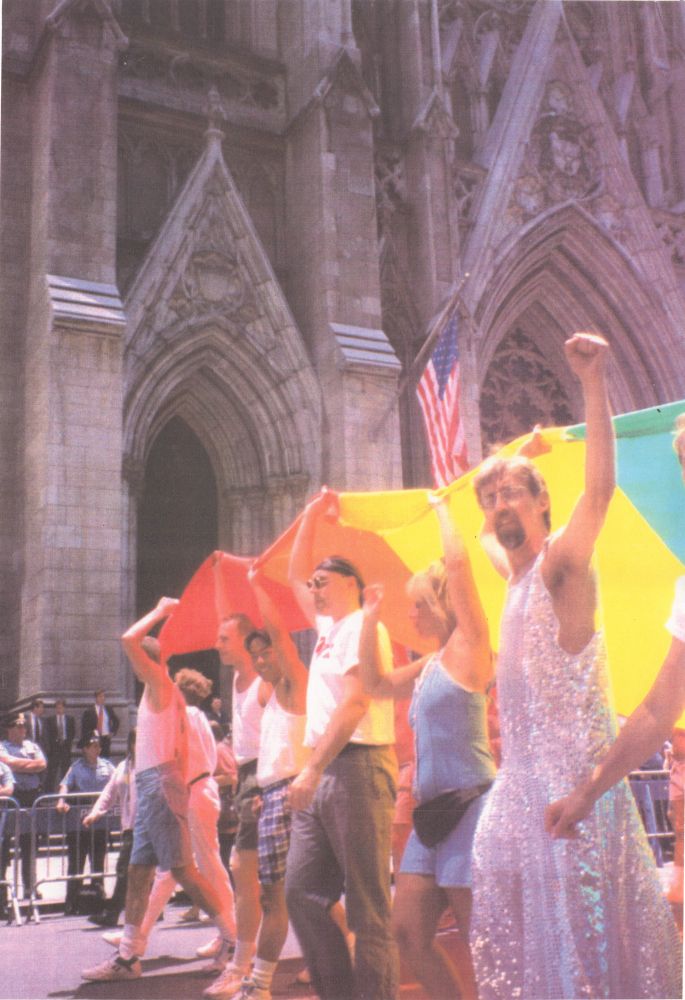

Baker felt that “Stonewall 25 was ultimately a commercial for marketing and merchandising the movement, an advertisement of power rather than an act of empowerment.” He decided, early in the morning of June 26, 1994, the day of the Pride March, to secretly veer from the agreed upon plan; once the flag, carried by about 5,000 volunteers, reached First Avenue and East 57th Street, Baker, wearing a handmade sequined gown, surprised nearly everyone by cutting the front of the flag into ten large sections. He and several friends each carried a section to an alternate, non-permitted Fifth Avenue march that had been planned to bring attention to the AIDS epidemic. Images of the Rainbow Flag on both avenues made the front page of the New York Times and other outlets, turning the flag, 16 years after its creation, into a globally recognized icon.

After the event, Stadtlander’s ended communication with Baker but kept the remaining flag, giving one-foot pieces to volunteers who helped carry it. Baker gave the ten sections he had cut to delegations from various countries, including Cuba, England, China, and Brazil, which flew them a year later (as of 2023, a large piece is in Cherry Grove on Fire Island and a six-foot section is in Pittsburgh). He later surpassed his own world record with a 1.25-mile-long flag for the 2003 Key West Pride in Florida. Baker’s last residence was in New York City, living in a garden apartment at 546 West 150th Street in Harlem from 2001 until his untimely death in 2017.

Entry by Amanda Davis, project manager (September 2023).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: James Polshek

- Year Built: 1986

Sources

“About Gilbert Baker,” Gilbert Baker, bit.ly/3sCfEIM.

Charley Beal, Gilbert Baker Foundation, email to NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, October 26, 2021; September 22, 2023.

“Gilbert Baker,” National Park Service, bit.ly/3L3aSuh.

Gilbert Baker, Rainbow Warrior: My Life in Color (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2019). [source of all Baker quotes]

Jason Slotkin, “Designer Of Rainbow Flag, Enduring Symbol For Gay Rights, Has Died,” NPR, April 1, 2017, bit.ly/3PjCONf.

Joanna Black and Jeremy Prince, “Performance, Protest & Politics: The Art of Gilbert Baker,” GLBT Historical Society Museum, bit.ly/45qy6Ti.

Matthew Haag, “Gilbert Baker, Gay Activist Who Created the Rainbow Flag, Dies at 65,” The New York Times, March 31, 2017, bit.ly/3L26ufj.

Paola Antonelli, “MoMA Acquires the Rainbow Flag,” Museum of Modern Art, June 17, 2015, bit.ly/3PiBQRo.

W. Jake Newsome, Pink Triangle Legacies: Coming Out in the Shadow of the Holocaust (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2022).

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?