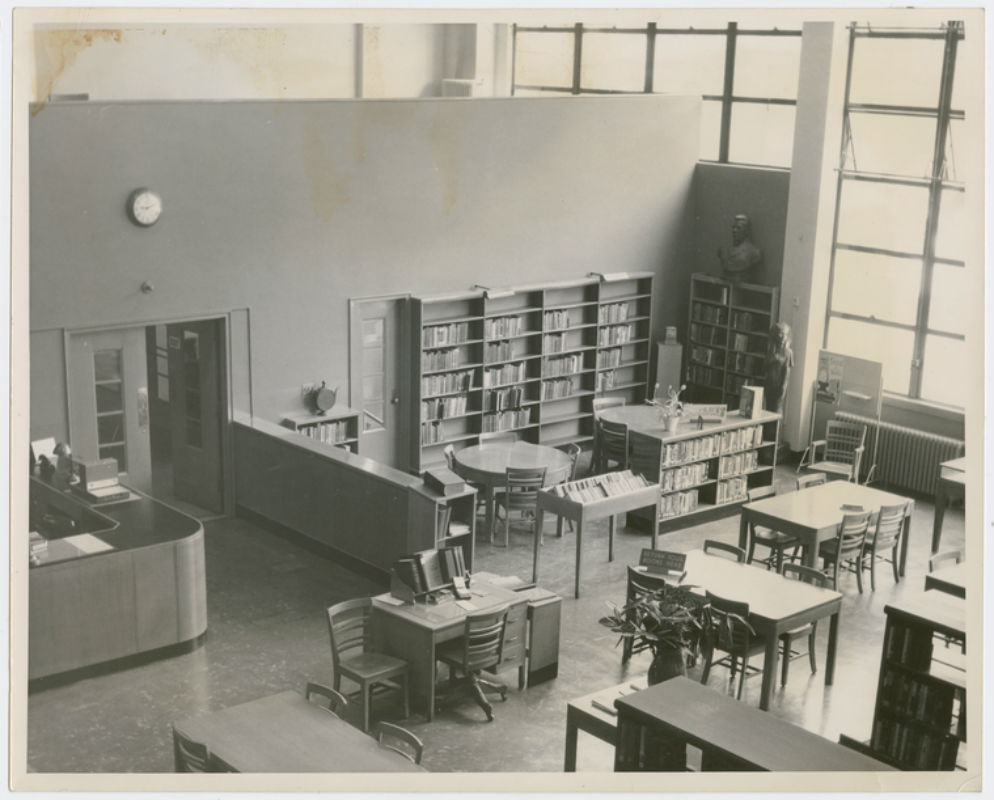

Countee Cullen Branch, New York Public Library

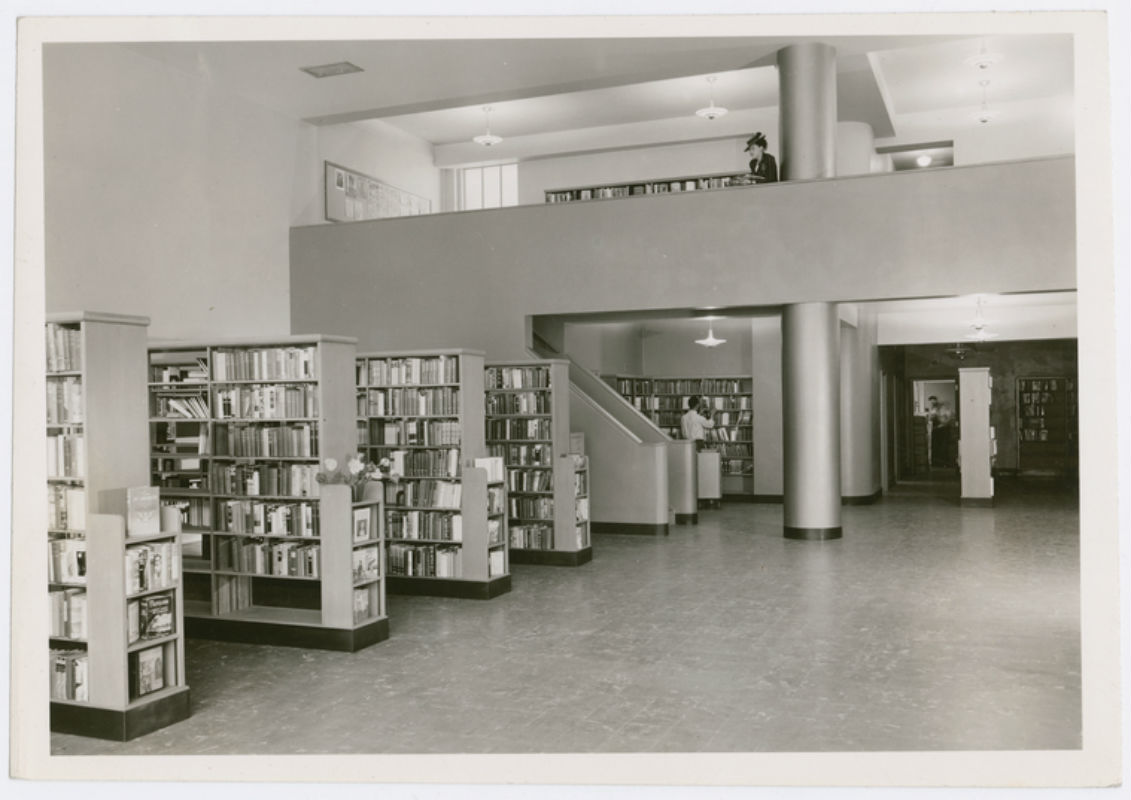

originally known as the 135th Street Branch in reference to the older library of the same name directly to the south

overview

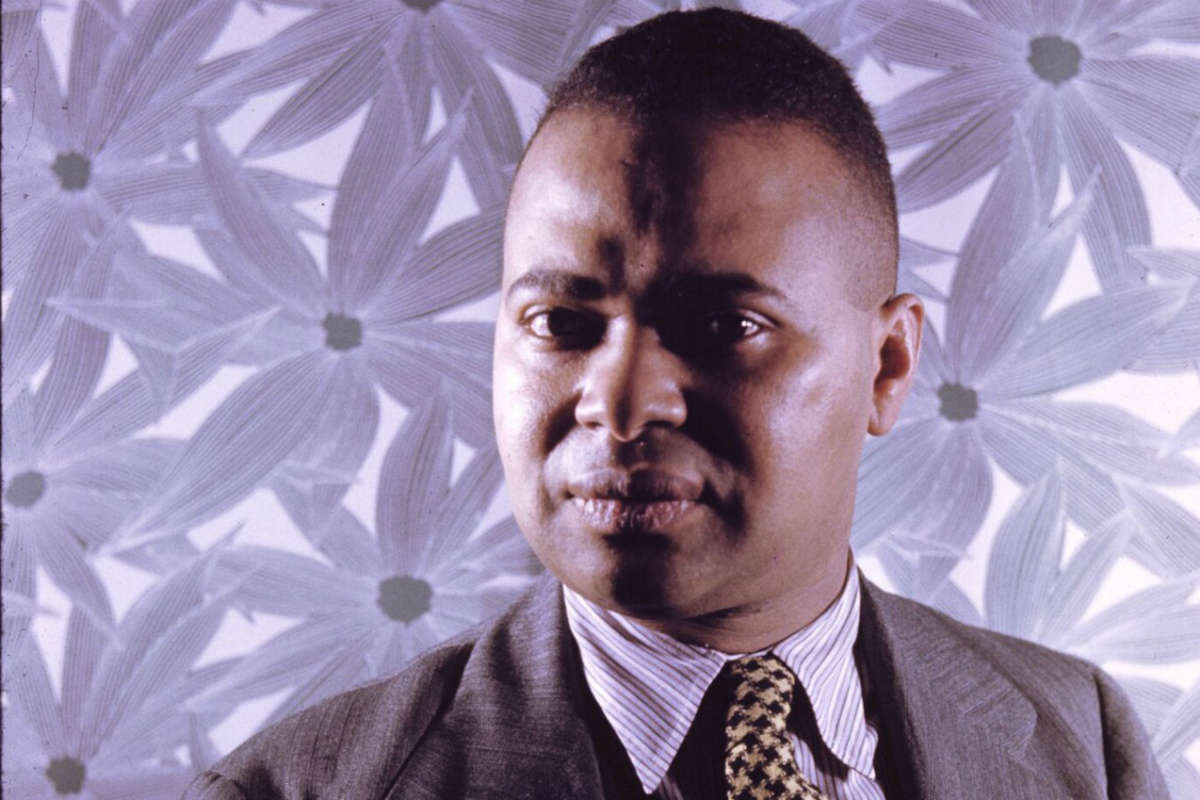

Renamed for the noted gay poet Countee Cullen in 1951, this library was the first in the New York Public Library system to be named in honor of an African American. Cullen, who died prematurely at age 42, was one of the preeminent figures of the Harlem Renaissance and included same-sex desire in his work.

Before the library’s construction, this site was occupied by a townhouse where, in a room called the Dark Tower, millionaire heiress A’Lelia Walker held lavish Harlem Renaissance-era parties that were welcoming to LGBT people.

On the Map

VIEW The Full MapHistory

In 1941, the New York Public Library (NYPL) had this building constructed to replace the older and smaller 135th Street Branch located directly to the south; the new facility took the name of the original branch, despite being located on 136th Street. A year later, prominent Harlem Renaissance intellectual Alain Locke spoke at the dedication ceremony. In September 1951, the library was renamed for poet Countee Cullen (1903-1946), becoming the first NYPL branch — and perhaps the earliest public building in the city — to be named in honor of an African American. (Although adjacent to the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, a research library of the NYPL, the Countee Cullen Branch operates as a separate library.)

Cullen, who frequented the original 135th Street Branch, was one of the few leading members of the Harlem Renaissance who grew up in Harlem. Born Countee LeRoy Porter, he changed his last name when Reverend Frederick A. Cullen, the influential pastor of Harlem’s Salem Methodist Episcopal Church, and his wife Carolyn, unofficially adopted him at age 15. Earning acclaim in literature at DeWitt Clinton High School (then located at 899 Tenth Avenue in Manhattan), New York University, and Harvard University, the young Cullen, “more than any other black literary figure of his generation, was being touted and bred to become a major crossover literary figure,” writes author Gerald Early, who also notes: “If any event signaled the coming of the Harlem Renaissance, it was the precocious success of this rather shy black boy. … If the aim of the Harlem Renaissance was, in part, the reinvention of the native-born Negro as a being who can be assimilated while decidedly retaining something called ‘a racial self-consciousness,’ then Cullen fit the bill.”

In 1925, Cullen published his first book of poems, Color, which soon after was one of the 135th Street Library’s earliest acquisitions for its newly-created Division of Negro Literature, History, and Prints. The latter half of the 1920s was his most prolific as a poet. By about 1922, Cullen had confided in Locke, who became a kind of father figure, about his attraction to men. Locke introduced him to Edward Carpenter’s gay-affirming Ioläus (1917), which helped the young poet embrace his same-sex desires. In a letter to Locke, Cullen wrote:

It opened up for me soul windows which had been closed; it threw a noble and evident light on what I had begun to believe, because of what the world believes, ignoble and unnatural. I loved myself in it.

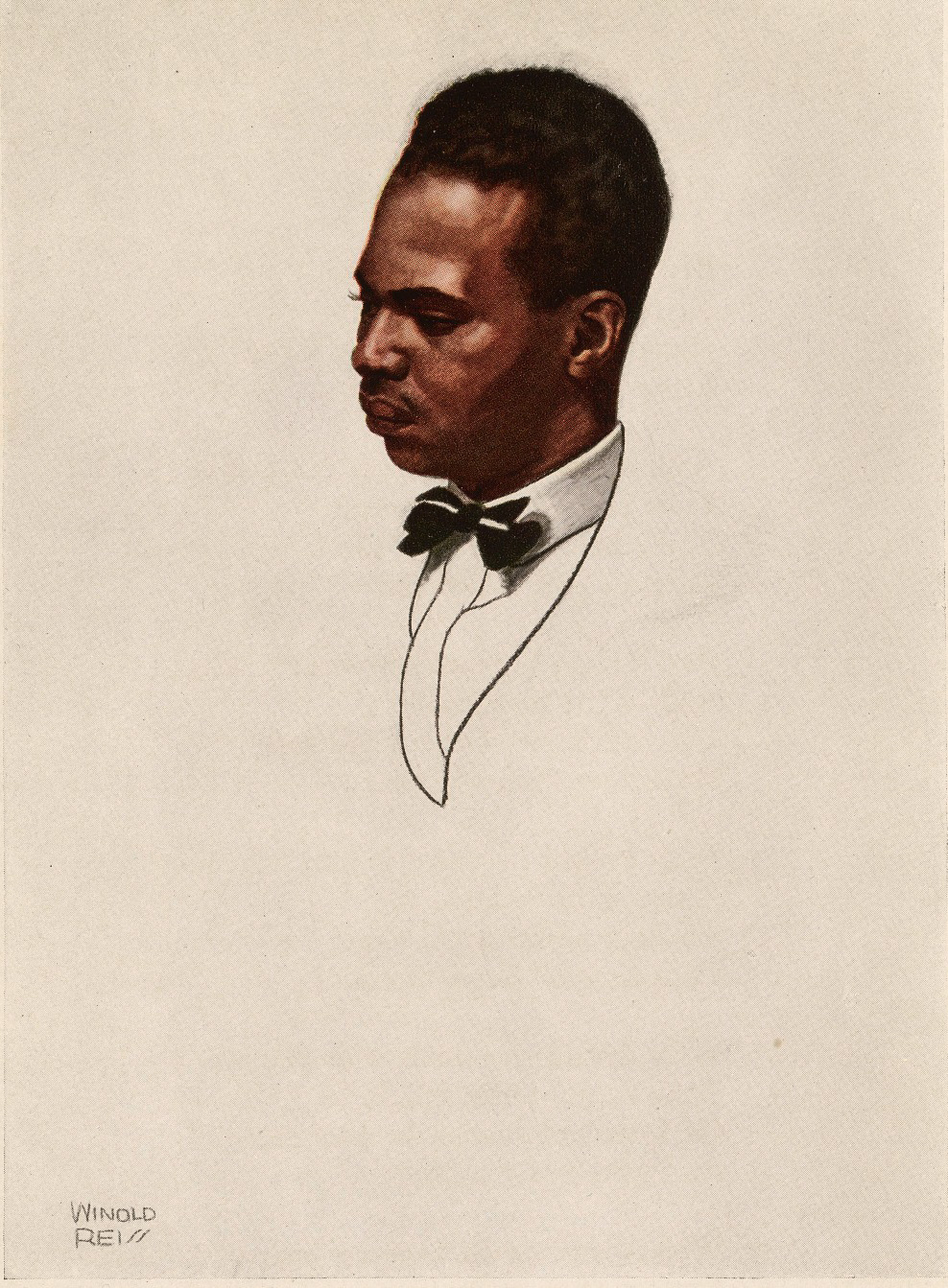

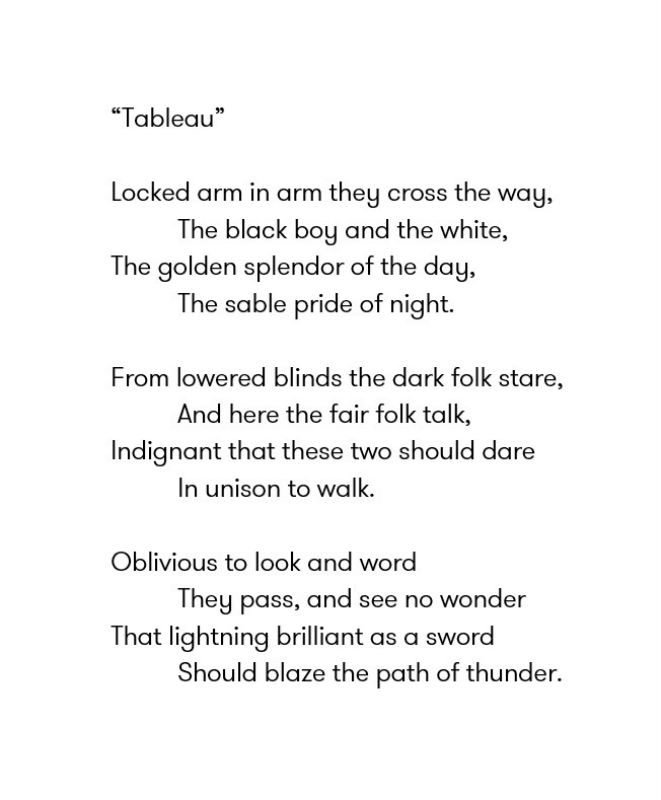

Though closeted and married twice to women, Cullen was likely gay rather than bisexual. He had sexual relationships with men throughout his adult life and dedicated poems to his lovers or friends with whom he was infatuated. Many of Cullen’s poems have coded gay language, including “Tableau” (dedicated to his former white lover, Donald Duff, after his death), “Fruit of the Flower,” “For a Poet,” “To a Brown Boy” (dedicated to Langston Hughes), “More Than a Fool’s Song” (dedicated to his then-lover Edward Perry), “The Black Christ,” “Yet Do I Marvel,” and “Song in Spite of Myself.”

In addition to his literary accomplishments, Cullen was considered a long-time friend of the 135th Street Branch and was actively involved in educating Black youth before his untimely death at age 42. From 1934 until his death, Cullen was a teacher — most notably to James Baldwin — at Frederick Douglass Junior High School (now Frederick Douglass Academy) at 140 West 140th Street. An estimated 3,000 people, including Locke, attended his funeral at Salem Methodist Episcopal Church.

Walker Studio (later, the Dark Tower)

Before the library’s construction, this site was occupied by the townhouse of entrepreneur Madam C.J. Walker, America’s first self-made female millionaire, who also ran her haircare empire here. During the Harlem Renaissance, her daughter A’Lelia Walker held lavish parties on the second and third floors, which she called the Walker Studio. In October 1927, the Dark Tower opened in a room in the studio. The famous salon attracted many notables; gay, lesbian, and bisexual attendees included Cullen, Alberta Hunter, Florence Mills, Langston Hughes, Edna Thomas, Olivia Wyndham, Carl Van Vechten, Mabel Hampton, Clinton Moore, and Harold Jackman. Historian Hugh Ryan notes that these parties “provided a safe, welcoming environment for queer people at a time when there were few other social options available. While she herself was not known to be lesbian or bisexual, Walker’s parties were places where anyone could express their sexuality however they pleased.”

The townhouse, designed by Vertner Tandy, the first Black architect registered in New York State, was demolished in 1941.

Entry by Amanda Davis, project manager (February 2018).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: Louis Allen Abramsom

- Year Built: 1941

Sources

“3,000 at Funeral of Countee Cullen,” The New York Times, January 13, 1946, p. 44.

“A Guide to Lesbian & Gay New York Historical Landmarks,” Organization of Lesbian + Gay Architects and Designers, 1994.

Amanda Casper, “Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture,” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form (Philadelphia: National Park Service, Northeast Regional Office, October 15, 2015).

Doug Ireland, “A Queer Harlem Poet’s Renaissance and Fall,” Gay City News, November 21, 2012, bit.ly/2F2qUox.

Gerald Early, “About Countee Cullen’s Life and Career,” Modern American Poetry, bit.ly/1zys9RF. [source of Early quote]

Hugh Ryan, “Remembering A’Lelia Walker, Who Made a Ritzy Space for Harlem’s Queer Black Artists,” NPR, September 22, 2015, n.pr/3k37mCy.

Lauren Walser, “How A’Lelia Walker and the Dark Tower Shaped the Harlem Renaissance,” National Trust for Historic Preservation, March 29, 2017, bit.ly/3CI1Fl3.

Rictor Norton, My Dear Boy: Gay Love Letters through the Centuries (San Francisco: Leyland Publications, 1998). [source of pull quote]

Sarah A. Anderson, “‘The Place to Go’: The 135th Street Branch Library and the Harlem Renaissance,” The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy, Vol 73, No. 4 (October 2003), pp. 383-421.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?