City Cemetery on Hart Island

also known as the city's Potter's Field

overview

Since 1869, Hart Island has been the site of the city’s public cemetery for burials of people who died indigent or whose bodies went unclaimed.

Beginning in the mid-1980s and through the 1990s, it became the burial location of reportedly thousands of people, many LGBT, who died of AIDS, which, if confirmed, would make it the single largest burial site in the country for those who died of the disease.

On the Map

VIEW The Full MapHistory

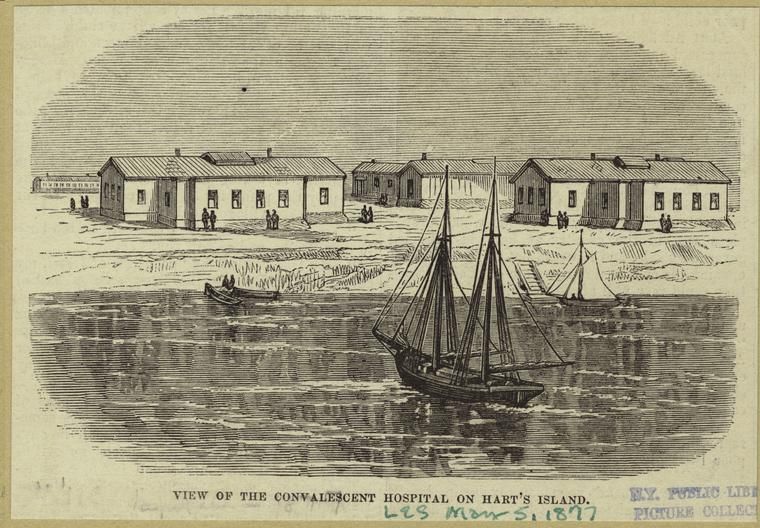

Located east of the Bronx in the Long Island Sound, the 101-acre Hart Island is reportedly the largest publicly-funded cemetery in the world with upwards of one million people buried there. Now officially known as the City Cemetery, and often referred to as the city’s Potter’s Field, in 1869, it began receiving burials of those who died indigent or whose bodies went unclaimed. From the mid-1980s through the 1990s, the height of the AIDS epidemic in New York City, approximately 100,000 New Yorkers died of AIDS, representing a quarter of those who died of the disease nationally during the same period. In 2018, an examination by the New York Times estimated that thousands who died of AIDS were buried on Hart Island although the exact number is unknown due to the lack of data from city agencies involved in the burials.

In the early years of the AIDS epidemic, the care and burial of those who died of AIDS was controversial and discriminatory. In 1983, the New York State Funeral Directors Association issued guidelines to not embalm those who died from AIDS. Fear and discrimination lasted well into the late 1980s, with many funeral homes, as well as religious institutions, refusing to accept the bodies of those who died of AIDS or charging higher prices for these services. Concurrently, general fear of the disease, stigma about homosexuality, and family estrangement, left many dying alone at home, in hospice, or at hospitals with their bodies unclaimed, leading to publicly-funded burials on Hart Island. In other cases, family members could not afford the cost of a private burial.

In 1985, the first documented burial of 17 individuals who died of AIDS took place on the island. Unlike the typical burial that took place in unmarked common graves in shallow trenches, these bodies were quarantined in a remote spot on the southernmost tip of the island in deep individual graves. Burial crews, at that time correction officers supervising Rikers Island jail inmates, wore disposable protective jumpsuits out of fear of being infected. As fear of transmission decreased, bodies of those who died of AIDS were included in the routine common burials. During the height of the epidemic, many bodies, including those of babies, were sent from hospitals with the largest AIDS wards and treatment centers, including Bellevue Hospital Center, St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital, Harlem Hospital Center, St. Vincent’s Hospital Manhattan, and St. Clare’s Hospital. Smaller numbers came from Rivington House and Terence Cardinal Cooke Health Care Center.

Up until 2014, the island was inaccessible to the families of those buried there and access still remains limited. In many cases, families are only now learning that a relative was buried on the island. The Hart Island Project and its AIDS initiative is working to identify those buried on the island, assisting families in finding unmarked burial locations, advocating for access as an open public cemetery, and disseminating the history of the island. In 2021, control of Hart Island was transferred from the city’s Department of Correction to the Parks Department due, in part, to the Hart Island Project’s advocacy.

In 2016, New York State designated the entire island as eligible for listing on the State and National Registers of Historic Places; no mention of its significant association with the AIDS epidemic is made in the resource evaluation.

Entry by Ken Lustbader, project director (January 2023).

NOTE: Names above in bold indicate LGBT people.

Building Information

- Architect or Builder: n/a

- Year Built: 1869

Sources

Corey Kilgannon, “Dead of AIDS and Forgotten in Potter’s Field,” The New York Times, July 3, 2018, accessed January 4, 2023, bit.ly/3IpWKuH.

Daria Merwin, “Hart Island Historic District – Resource Evaluation,” New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation, October 4, 2016.

Derek Kravitz and Jacob Geanous, “Hart Island Burials Taken Over By Tree Landscapers, Uprooting Families’ Hopes for Transformation,” The City, November 18, 2021, accessed January 4, 2023, bit.ly/3Gkrgnf.

“Hart Island: The City Cemetery,” New York City Council, accessed January 4, 2023, bit.ly/3if1aKi.

The Hart Island Project, accessed January 4, 2023, www.hartisland.net/.

John Freeman Gill, “Streetscapes: Hart Island’s Last Stand,” The New York Times, July 16, 2021, accessed January 4, 2023, bit.ly/3ZcLojt.

Mary Jordan, “The Forgotten Dead: She died in a Manhattan penthouse but was buried on an island for the poor,” The Washington Post, July 2, 2022, accessed January 4, 2022, bit.ly/3ClhsYY.

Nina Bernstein, “Unearthing the Secrets of New York’s Mass Graves,” The New York Times, May 15, 2016, accessed January 4, 2023, bit.ly/3GGdUDa.

Sharon L. Bass, “Funeral Homes Accused of Bias on AIDS,” The New York Times, November 15, 1987, accessed January 4, 2023, bit.ly/3WKh1PP.

“Undertakers Unit Warns of AIDS,” The New York Times, June 18, 1983, accessed January 4, 2023, bit.ly/3VGqbf7.

Do you have more information about this site?

This project is enriched by your participation! Do you have your own images of this site? Or a story to share? Would you like to suggest a different historic site?